JOE ZAWINUL / “Birdland”

Another road trip. Unwelcomed. There is even, perhaps a touch of dread. Definitely wearying. Half past midnight, I closed the door. Locked it. Checked it. Turned my back. Joined my wife in her car and drove off into the warm, humid night. We were evacuating New Orleans. The last time we left—three years ago, almost to the day—we were going over to Houston to stay a few days with Voris, my brother-in-law, until Katrina blew over. We thought we would be gone only two or three days. Four, five at the most. Then the reality hit—it was two months before I was back in our home. There is not much optimism this time. We witnessed what happened with the last hurricane visit. The levee failures. The dearth of effective post-disaster leadership. The painfully slow, uneven and ultimately frustrating rebuilding process. In the interim, Voris died. And so have our smiles and our confidence that we can deal with this next disaster. Gone. We know: there is a lot we can’t deal with. We know: the water can be a killer. We know: the devastation can be both deep and widespread. This next storm, this Gustave, this hurricane that threatens to hit us from the opposite direction compared to where Katrina socked us. We are still reeling, We were hit flush and spun around and just when we had wiped away blood from our split lips, from our broken noses; just when we had gathered ourselves and were in the midst of fighting back, here comes another huge roundhouse. No one can not keep repeating the rupture, least of all we New Orleanians. Of all the major cities, we have the highest percentage of people who live and die in the same city where we were born and grew up. It is too much. The heart seizes up, the spirit withers, the brain sends an umistakable message: are you crazy? Why do you continue? Are you really going back, will you really stay when you return this time? Why? Like counseling a domestic abuse survivor who is in deep denial: why do you keep going back? Why do you put up with it? You know you can do better. By the time most of you read this, we will know how well our city did or did not survive Gustave. We will know, or at least have a good idea, of the extent of major damage—and yes, it is almost a given, there will be major damage, if not to us, then to one our neighboring communities: a small town on the coast like Grand Isle or Morgan City, or to nearby low lying areas like Waggman, where Ashley lives (just this past Thursday night she returned to grad school in Savannah, Georgia), or to the Woodmere subdivision in Harvey, where my dear friend Marian lives, Marian who took the time to call and let me know she was OK and had retreated to Shreveport, her childhood home. We all will know and I know the knowing will be nothing nice. …we now return you to our regularly scheduled programming. P.S. I am safe in Atlanta with friends. —Kalamu ya Salaam

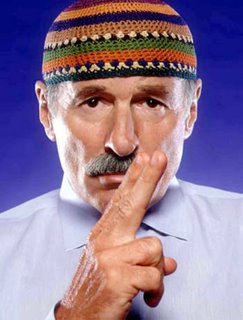

Josef Erich Zawinul, BKA Joe Zawinul, aka The Viennese Wonder. I remember seeing him sitting at a bar after a Cannonball set. People say it all the time, and in this case it was I also say it: there was something about him.

I never followed up on that feeling. Enjoyed his playing with Cannonball and didn’t think too much about it.

I, along with a legion of jazz fans, liked Miles’ album In A Silent Way (1969). Zawinul had written the title song. A year later, 1970, Weather Report hit. Initially I was ambivalent, and definitely not a big fan until they dropped Black Market (1976). Man, I loved that album. I also liked their album 8:30 (1979), but in general Weather Report just wasn’t my cup of spearmint herbal tea. In the new millennium Zawinul did a solo album and debuted a new band. I did not pay a whole lot of attention.

Fast forward, Mtume and I were discussing what we would do for this week. Usually we choose categories and then wait to see what each other comes up with. Mtume said he wanted to feature the Polish jazz trumpeter Tomasz Stanko. I had some of his music and said cool. I said I was going to do such and such and so and so. I ended up doing neither. C’est la vie.

Enter Joe Zawinul. I started researching. The more I researched, the more I said, well, alright. I’m down with that. Check him out.

Josef Erich Zawinul, BKA Joe Zawinul, aka The Viennese Wonder. I remember seeing him sitting at a bar after a Cannonball set. People say it all the time, and in this case it was I also say it: there was something about him.

I never followed up on that feeling. Enjoyed his playing with Cannonball and didn’t think too much about it.

I, along with a legion of jazz fans, liked Miles’ album In A Silent Way (1969). Zawinul had written the title song. A year later, 1970, Weather Report hit. Initially I was ambivalent, and definitely not a big fan until they dropped Black Market (1976). Man, I loved that album. I also liked their album 8:30 (1979), but in general Weather Report just wasn’t my cup of spearmint herbal tea. In the new millennium Zawinul did a solo album and debuted a new band. I did not pay a whole lot of attention.

Fast forward, Mtume and I were discussing what we would do for this week. Usually we choose categories and then wait to see what each other comes up with. Mtume said he wanted to feature the Polish jazz trumpeter Tomasz Stanko. I had some of his music and said cool. I said I was going to do such and such and so and so. I ended up doing neither. C’est la vie.

Enter Joe Zawinul. I started researching. The more I researched, the more I said, well, alright. I’m down with that. Check him out.

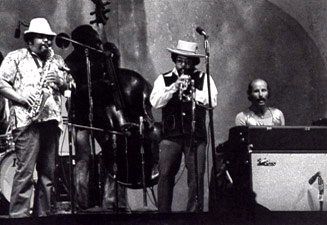

My goal was always to get on scenes where I was the weakest one going in and the strongest coming out. Like you learn from your daddy and then go a little bit further. The midget on the shoulders of the giant. —Joe ZawinulThis quote tells you a whole lot. First, he understood the basic jazz principle that you learn best by playing with people who are better than you. Second, any one and every one who has made a major contribution to creating new styles of jazz has first mastered an earlier form. Monk could play stride. Ornette could play Bird. And so on. Zawinul is right in the pocket of stepping back in order to leap forward. When Zawinul arrived in the United States, he attended Berklee College of Music in Boston. Within a couple of weeks, his instructors told him, there’s nothing we can teach you. You should go out and start working. You’re already ready. Zawinul joined trumpeter Maynard Ferguson’s band, and from there went on to work and record with Dinah Washington. In 1961 he was recruited by Cannonball Adderley. That’s when things really took off.

Two notes of trivia. 1. Soul jazz pianist Bobby Timmons preceded Zawinul in the Adderley band. Arguments at that time were raging in Downbeat: could whites play soul music? Could they swing like blacks? Can you tell if a musician is white or black just by listening to them play? Etc. Etc.

Then Zawinul wrote “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” And then he wrote “Walk Tall.” And then, oh yeah, “Country Preacher.”

How could this be? Joe Zawinul was born July 7, 1932 in Vienna, Austria, that great bastion of Soul music! Not only was he so-called “white” he wasn’t even American.

In 1992 Zawinul released an album titled My People about which Zawinul said: "My people" are not just Austrians or white people. It seems to me that when anybody talks about "my people" it's about people who are of their race or nationality. I wish most people could get away from this concept so we can look at ourselves as all being from out of one pot.

Two notes of trivia. 1. Soul jazz pianist Bobby Timmons preceded Zawinul in the Adderley band. Arguments at that time were raging in Downbeat: could whites play soul music? Could they swing like blacks? Can you tell if a musician is white or black just by listening to them play? Etc. Etc.

Then Zawinul wrote “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” And then he wrote “Walk Tall.” And then, oh yeah, “Country Preacher.”

How could this be? Joe Zawinul was born July 7, 1932 in Vienna, Austria, that great bastion of Soul music! Not only was he so-called “white” he wasn’t even American.

In 1992 Zawinul released an album titled My People about which Zawinul said: "My people" are not just Austrians or white people. It seems to me that when anybody talks about "my people" it's about people who are of their race or nationality. I wish most people could get away from this concept so we can look at ourselves as all being from out of one pot.

Anil Prasad: Describe the message you wrote My People to convey. It’s a beautiful record. I like it a lot—it’s one of my favorites. It says a lot of the things I want to say. It’s more philosophy than music. There’s a real communication within all of us and so many people deny their own thing. I always believe in the fact that the world is one thing—even when I was a kid we were in war and in spite of what happened, I always believed in the humanity of people of the world. I’m talking about all kinds of people. I grew up with that idea of many tribes. I believe that all people are great in every nation. I’ve been all over the world and I consider all of these people to be my people.

What motivated you to make the statement now?

I heard an interview on CBC Radio in Canada with Duke Ellington and he talked about the idea of "my people" and I thought he made the same statement I've been making throughout my entire life. Duke is really one of my favorites. He made a great impact on my life. So, I said to myself, "that's what I want to express" and I decided one day to make a record about that. Therefore, I have many people from many tribes singing on the record. My favorite instrument is singing when it’s done right, but it can be the absolute worst when it’s not. In every culture, there are a handful of really outstanding storytellers. That’s what it is all about—music is nothing else. Music is not a bunch of notes and chords. Music is storytelling.

—Joe Zawinul2. Joe improvises his compositions, i.e. he plays and then writes down what he played. Even his major orchestral piece was improvised.

My songs are all improvised. I sit down and compose an entire song from start to finish. I change nothing. Later, I might think of a hipper chord, but I never go back and put it in. I believe in nature and what nature gives me. —Joe Zawinul

Today’s improvisation is too based on the knowledge of chords and the way they practice the chords. It's not a melodic thing anymore like the older days. It was much more important to play shorter and to play more variable, valid stuff. Today, a lot of solos are long and uninteresting and the influence usually comes from John Coltrane's group. He, himself was a master musician, but he put so much emphasis on chord knowledge and technique, and now the kids want to show how fast they can play. This is the same with piano players and most instrumentalists—it's speed. That’s gonna change again and hopefully the kids who are now 16 and 17 years-old have a little more sense and maybe some more stories to tell. The other kids from the other generation came right out of school and immediately got a record contract. Do you know how difficult it used to be to get a record contract in the olden days? It was almost impossible. And then if you did, the record distribution was so tiny and small. It was very difficult.

—Joe Zawinul

Dizzy [Gilliespie] once called me to say "Man, I just heard one of your records. That's music man." That really made me feel good because we had some funny backlash from people who said we were selling out because we were using electronic instruments. It's such idiocy. It’s ridiculous that someone could place that much importance on the instrument to be that great. An instrument is not important. It is the way one plays that is important. Instruments don’t play by themselves. A piano is certainly not a better instrument than a synthesizer, but if a synthesizer is played like a piano, it becomes a very bad instrument. It doesn't work. You can't play a trumpet like a violin—it doesn't go. That's the problem—the players, not the instrument. Any instrument is a wonderful thing.

—Joe Zawinul

* * *

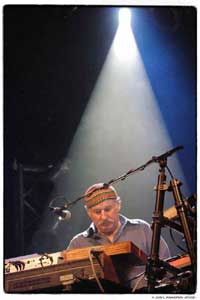

It is not easy in jazz to be a major innovator who changes the entire course of jazz. Joe Zawinul is one the creators of fusion. There are many people who are major musicians, such as Rashaan Roland Kirk. As individuals they are hugely important but that doesn’t mean they change the course of the music as a whole. As much as I have come to admire and enjoy Zawinul’s music, my take is that he has had a stronger impact as a stylist than as a player.

It is not easy in jazz to be a major innovator who changes the entire course of jazz. Joe Zawinul is one the creators of fusion. There are many people who are major musicians, such as Rashaan Roland Kirk. As individuals they are hugely important but that doesn’t mean they change the course of the music as a whole. As much as I have come to admire and enjoy Zawinul’s music, my take is that he has had a stronger impact as a stylist than as a player.

Le Bananier Bleu: Africa obviously plays a big part in your music. It seems to me that you have a lot of African influences.

JZ: Not so much. I'll tell you the truth, and I only realize that now. My African influences are much less than my influence on African musicians, because they grew up with my music, and I did not grew up with their music. I am not a music listener. Until I met Salif Keita, I had not heard any African music. That's how it is. These young guys like Youssou N'dour, Salif, the guys in South Africa, in Nigeria, they grew up with Weather Report. And they added this to their traditional music and then it became what has been called World Music. And sometimes now, people ask me : "Well Mr. Zawinul, now are you playing world music?" But that's not true, it is the other way around. I have spent time with Paco Séry and Etienne M'bappé who told me they said they spent days and days listening to Weather Report, and they knew everything we did. It's important to tell to people what the truth is. That's the thing, I have musicians from different places in the world. This is different, because Weather Report was more or less an American band and I was the only foreigner in it. I have found that young American musicians have gone in their own direction (hardly influenced by the recording companies) to continue playing bebop, and bring bebop back. I think this was a major mistake, because, what it did was stop everything. Musicians, in other parts in the world, from Argentina to Australia, to China, or Turkey, they come from Weather Report. And on top of this, they built. They also heard bebop, but they didn't want to be bebop musicians. Because we had freed music. We were the ones who took the chains off the music. You got to get away from the system. Four bars, repeat an A, middle part, and then the last eight bars of music... first solo is the saxophone, and then trumpet, piano, bass solo, 4/4 on the drums etc. We stopped all that! And the funny thing is that Wayne Shorter and myself independently changed the bar lines of the music. And we have been very successful in what we've done. Today there's the rest of the world... America's still America. There are great musicians there, but let's say just in progressive music I don't know anybody right now there I would spend money on. But in other parts of the world they bring all their traditions to the music and together with American tradition, and with what we did with Weather Report. And it is fresh! In France, in England, everywhere there are very good players. In America, they're playing good too, but there are only a few who really went in the direction I talked about. There are guys like Christian McBride and some others who took up where we left off and went in another direction. I like very much what they are doing. I don't like people playing bebop piano, bebop lines like in the 40's. —Joe Zawinul

* * *

I'm not afraid of death. The reason could be that I grew up in an environment in which I was always exposed to death every day for years. Experiencing bomb attacks in the night and day and actual war in your country is very different than watching a war from 1000 miles away from your home. We had the war right there in my house. The Russians came in and many of my friends died, so this type of life prepares you for death. An 11 or 12 year-old kid in America will play with a rubber duck, whereas I used to bury people—dead soldiers and all that. When I was 12, I used to steal horses from the Russian wagons and kill them for food. I ploughed fields with Oxen. That was my life. The kids were the men. I was trained for the military—I was a bazooka man. But going back to mortality, I felt when the war was over, everything was easy, but I went through some very hard times in America too. I was the only white guy to play with black bands in the South during segregation. I often had to sit in the bottom of the car when we drove through certain parts of the South. Those kinds of things never phased me—I wanted to play music with the best and I could play on that level with the best. —Joe Zawinul

Everything is in decline the moment you stop giving the artist freedom. That goes for everywhere, but it is happening in America right now. I think record companies are at great fault. In general, they don’t want to develop talent, but rather get the most out of them in the short-term. They’re steering people to things they perhaps wouldn’t do but have to do and not everyone has the integrity to say "No way." People are hungry and they have to make money and take care of their families, so it’s a great pressure. Only when you can afford it from an artistic or financial point of view can you express what you want to express. Before I made My People, I was with Sony for a long time and then there was interest from Verve Records over at Polygram. They told me at the first meeting I had with them—and it was the only meeting I had with them—that they wanted me to sign up but only to play acoustic piano on the first record and only Duke Ellington’s music. I got up and left.Despite you being a big Duke Ellington fan?

I'm the Duke Ellington fan, but that had nothing to do with it. They were telling me what to do and not only that, it was a question of "What is in it for me to play Duke Ellington’s music? I'm a composer. I like my music and I like it as much as I like Duke Ellington's music. Duke is one of the greatest musicians who ever lived, but everybody is an individual and it has nothing to do with being better or not as good. It's about the storyline—what you have to tell. And in that respect, I like my music just as much. It sounds very different, but in principle it's still the same.

So, where have the individuals—the storytellers—gone?

They are many storytellers, but they're hidden somewhere. In the older days that's all you had. You didn't have these phenomenal music schools which are everywhere today. That was not so good because the people didn't play their instruments as well as they do today. That was the way times were. If you didn't have a sound of your own, you couldn't make it. All the guys I used to play with when I came to America—each one was a different individual. They had different sounds and different ways of playing and that's what made the business go around. But today, jazz has become very boring. And when I talk about jazz music, I'm talking about who everyone talks about when they talk about jazz. People tend to toss names such as Wynton Marsalis and Keith Jarrett around when the word "jazz" is invoked in the mainstream these days. To me, this is very boring music—most of it. It has nothing happening. Nothing is sticking. They're playing music perfectly with wonderful intonation and technique, but it's dangerous for jazz itself. I do wish these people all the best. I’m happy that it goes like that in a way because we used to live like rats when I didn’t make any money. We used to have to play every night and drive everywhere. We didn’t have the accommodations available today. It was a difficult time, believe me. We all had families to support. I very much respect Wynton as a noble guy who is doing a lot for keeping the great names alive, but the music comes out short. Those little upstarts—that age group, it’s not happening. When I listen to old Cannonball, Horace Silver, Blue Mitchell, Art Blakey and Miles stuff, it’s way, way, way superior. It’s in another league—the fire, the excitement. But that doesn’t mean the new guys don’t have it, they’ve just been geared to do the same stuff. I was able to afford to say no, but how many people can say no to a major league contract? Wynton has enough power to do what he wants to do, but it's just not my cup of tea.If I was coming up now I don't think I'd like to be going in their direction musically. But it's not their fault and it's not criticism because it's not just music. Everything happens like that. It's a spiral going down. In the arts, music and movies, everything is now geared up to a specific audience—the young people, who in general listen to music. And it’s not music anymore. Rock & roll was a great movement and very important to all of our lives, but it happened. It made it possible for jazz musicians to get a piece of the rock. It was a great change and cultural movement but the way it's developed has got more and more ugly. The way songs are being performed today compared to the older days—now, you don't understand the words and they have so many embellishments and very little substance. I hope I don’t sound like I have sour grapes. I'm a very happy, happy person. But if you ask me, I'll tell you what I think and it's just not happening for me. —Joe Zawinul

* * *

In the jukebox are three of Zawinul's biggest hits when he was with Cannonball: "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy," "Walk Tall" and "Country Preacher." "In A Silent Way" is Zawinul's huge contribution to the Miles Davis output of innovative albums. From the Weather Report days, I've included, Zawinul's most popular composition: "Birdland"—be sure not to miss the use of the "soul clap" briefly at the end of "Birdland." And I conclude with four cuts from Zawinul's last band, The Zawinul Syndicate. The track that samples Duke Ellington's voice illustrates the depth of Zawinul's respect for Duke. Additionally the Ellington composition "Come Sunday" was a feature for Zawinul when he was with Cannonball. Here Zawinul has recast it for his last band and he in turn features vocalist Sabine Kabongo who has sung with Zap Mama. Enjoy the music of Joe Zawinul. Although he died on September 11, 2007 of skin cancer his music continues to inspire. —Kalamu ya Salaam JOE ZAWINUL MUSIC: All three of the Zawinul compositions with Cannonball are available on Cannonball Adderley Greatest Hits [Capitol]. "In A Silent Way" is available on Miles Davis In A Silent Way. "Birdland" is available on Weather Report Heavy Weather. The four Zawinul Syndicate tracks are available on Vienna Nights: Live at Joe Zawinul's Birdland. Even stranger Everything I know about Joe Zawinul comes through his work with Miles or Cannonball. I don't have any Weather Report (I know, sue me) and I've never heard any of his solo work until now. Except for his version of his own "In A Silent Way," a version I actually like better than the classic Miles Davis one. You know what. I can't lie. I've heard all the Cannonball tracks in the jukebox but I had no idea Joe Zawinul was the pianist. If there really was a debate about whether or not a white cat could play with soul in a jazz context, I guess Joe answered that one, right? I remember Kalamu trying to break down what soul-jazz was all about. Tracks like these were right at the heart of that conversation. And Zawinul wrote them. That's funny. Zawinul was also a versatile cat, obviously. Other than being jazz classics, "In A Silent Way" has nothing in common with "Walk Tall." The fact that he's from Vienna only makes a strange story even stranger. RIP, Joe. —Mtume ya SalaamThis entry was posted on Tuesday, September 2nd, 2008 at 3:29 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

4 Responses to “JOE ZAWINUL / “Birdland””

September 2nd, 2008 at 7:48 am

Kalamu,

Glad to hear you are safe. We have been keeping the people of New orleans in our prayers. from the news reports, it looks like the brunt of the hurricane has moved through without overwhelming damage – hope this continues as it moves on its path. let us know when you get back home and what the situation really is – physically, psychologically, spiritually…

Perhaps it’s time to revisit the culture and explore and re-explore the heart of New Orleans music. When i was in new Orleans last month, Nicholas Payton was at Snug Harbor and performed a mournful and energetic tribute to post Katrina NOLA, and i picked up a new irma Thomas CD recently, although I haven’t had a chance to listen to it.

peace,

sue

September 4th, 2008 at 4:44 am

I’ve always loved Zawinul’s keyboard playing style. Great post! thanks.

April 17th, 2013 at 7:18 pm

Hi! Would you mind if I share your blog with my zynga

group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Thanks

Leave a Reply

| top |