ERNESTINE DEANE / “Prayer For Cape Town”

Let’s trip, cover the four coasts of Africa, hear the sisters sounding West, North, East and South. Let’s sample, as it were, femme songs, women singing survival songs, touching the soft and the strong of their lives and sharing that touching with us.

* * *

1. West. Ivory Coast. Manou Gallo. What would you do if you were a little girl growing up in the village of Divo in the western region among the Djiboi people? You were born on the tip of August’s tail, the 31st, in 1972, and the only mother you knew was a grandmother.

1. West. Ivory Coast. Manou Gallo. What would you do if you were a little girl growing up in the village of Divo in the western region among the Djiboi people? You were born on the tip of August’s tail, the 31st, in 1972, and the only mother you knew was a grandmother.

At this time, I was living like a little savage. I was helping cultivating the fields, drawing water from the well. I wasn't going to school, but my grandmother taught me traditions, respect, and values. When I was a little girl, I was already going from backyard to backyard, these places where each family comes together everyday to cook, sing, in one word to live together. I was meeting my girlfriends and sooner or later we inevitably started singing, dancing and beating on iron boxes. —Manou GalloWhat would you learn? Manou learned music. Drumming came to her and stayed with her even though among her people drumming was not an approved activity for females. Did she let tradition stop her? (If you go here you can see her open a song with a drum solo.) Manou’s life is the fabric of legend. (All quotes are from her website.) Her big break came at a funeral. The scheduled drummer had not arrived. Manou dragged a stool over to the “Atombra,” the talking drums, climbed up and beat out the rhythms.

Everybody was really astonished, and a bit shocked also since women are not allowed to touch these drums. In some extent, they were taking me for a witch. My grandmother was supporting me and on this occasion, she explained to me that this was a gift, transmitted to me through a dream her own mother had and who died the day I was born. When at the age of 8, I was getting seated to play drums during this ceremony, I could feel the power of my ancestors on my fingertips.Not yet a teenager, Manou was celebrated as a musician possessed by the power. Even detractors were unable to deny her skill—they accused her of evil powers. Manou's grandmother defended her and Manou continued on her path. At 12 Manou took part in a national artistic competition called Vacances-Culture and for the first time in her life traveled outside her village. The following year, in 1985, Manou was invited to join Woya, a professional band that was famous throughout West Africa. Up until leaving the band in 1989, Manou toured and recorded on four albums with Woya.

I was the little one who was opening the concert with the talking drums. During the rest of the show I would just beat on a bell. This, however, is when I discovered modern instruments: the drums, the bass, and the guitar along with the person who became my spiritual father and who played a major role in my life. This person was Marcelin Yacé, musician and conductor of the band.When Woya dissolved, Manou went with Marcelin to Abijan and spent three years under his tutelage. “I was only thinking about music. I only had one objective: To become a full-fledged musician and I was investing all my energy in this.” Then came the fateful day her mentor sent her away for further study. Rather than to sending her to France for formal study, Marcelin wisely sent her to the pan-African village of Ki-Yi-Mbock where she studied with a theatrical group, learned to dance as well developed a deeper understanding of music. She end up working on a recording by internationally celebrated keyboardist/composer Ray Lema.

In 1992 while performing in Abdijan at a pan-African showcase, Manou met Michel De Bock, tour manager and lighting engineer for Zap Mama. After the initial contact, Michel thought of Manou when Marie Daulne, the leader of Zap Mama, decided to add musicians to the Zap Mama sound and was seeking a bass player. When Manou Gallo landed in Belgium she carried her bass and djembe drum. Michel’s offer was for an audition although Daulne already had someone else in mind. After three intense days of singing, dancing, drumming and bass playing, Manou secured the gig.

Manou’s tenure with Zap Mama lasted from 1992 through 1998. Not bad for a street “urchin” who had previously earned money selling oranges. For an encore, Manou co-produced her debut album Dida in 2003. The first two tracks (“Iniyi” and “Nayouwy”) are from Dida. The remaining three tracks (“Stars,” “Apoahayo” and “Polyne”) are from Manou Gallo, Manou’s eponymous 2007 release on the Zig Zag World label.

In 1992 while performing in Abdijan at a pan-African showcase, Manou met Michel De Bock, tour manager and lighting engineer for Zap Mama. After the initial contact, Michel thought of Manou when Marie Daulne, the leader of Zap Mama, decided to add musicians to the Zap Mama sound and was seeking a bass player. When Manou Gallo landed in Belgium she carried her bass and djembe drum. Michel’s offer was for an audition although Daulne already had someone else in mind. After three intense days of singing, dancing, drumming and bass playing, Manou secured the gig.

Manou’s tenure with Zap Mama lasted from 1992 through 1998. Not bad for a street “urchin” who had previously earned money selling oranges. For an encore, Manou co-produced her debut album Dida in 2003. The first two tracks (“Iniyi” and “Nayouwy”) are from Dida. The remaining three tracks (“Stars,” “Apoahayo” and “Polyne”) are from Manou Gallo, Manou’s eponymous 2007 release on the Zig Zag World label.

Manou’s music is intriguing—first of all because Manou continues to sing most of her songs in Dida, her mother tongue, even though she is now based in Brussels and is an advocate of cross-cultural music. Too often “cross-cultural” has come to mean elevating Euro & American influences while diminishing indigenous elements until the indigenous is a mere accessory or spice rather than the main item. This transformation is especially prevalent when an artist is attempting to reach an international audience. (Again, "international" has come to mean a European and/or America audience.) Manou’s steadfast refusal to silence her root-tongue is laudable; in the face of the power of the dollar (or actually the uber-power of the euro), for a young woman from an internationally unrecognized village in the interior of Ivory Coast to hold fast to her roots is heroism of the highest order.

Music has been Manou's salvation and continues to be the way she makes her living. She lives abroad but she sings of home.

Manou’s music is intriguing—first of all because Manou continues to sing most of her songs in Dida, her mother tongue, even though she is now based in Brussels and is an advocate of cross-cultural music. Too often “cross-cultural” has come to mean elevating Euro & American influences while diminishing indigenous elements until the indigenous is a mere accessory or spice rather than the main item. This transformation is especially prevalent when an artist is attempting to reach an international audience. (Again, "international" has come to mean a European and/or America audience.) Manou’s steadfast refusal to silence her root-tongue is laudable; in the face of the power of the dollar (or actually the uber-power of the euro), for a young woman from an internationally unrecognized village in the interior of Ivory Coast to hold fast to her roots is heroism of the highest order.

Music has been Manou's salvation and continues to be the way she makes her living. She lives abroad but she sings of home.

The second element that impresses me about Manou’s music is her use of not only African rhythms but also African melodies and harmonies. Again, while seeking the fruit of worldwide musical acceptance she has been careful not to eschew her own cultural specifics. This is significant because most so-called advancements in “world music” are usually based on absorption into Euro-centric aesthetics.

Clearly Manou’s years spent studying African music have produced a person with ears wide open, i.e. she is capable of hearing and using a wide range of cultural influences. But Manou is also an advocate of her own African aesthetics. She is a perfect example of learning from others without losing a sense of self. Her music is wonderfully rich. For example, if you want rock, a la heavy metal, she can and does rock out, but in the same song she will include a djembe or conga drum solo.

The second element that impresses me about Manou’s music is her use of not only African rhythms but also African melodies and harmonies. Again, while seeking the fruit of worldwide musical acceptance she has been careful not to eschew her own cultural specifics. This is significant because most so-called advancements in “world music” are usually based on absorption into Euro-centric aesthetics.

Clearly Manou’s years spent studying African music have produced a person with ears wide open, i.e. she is capable of hearing and using a wide range of cultural influences. But Manou is also an advocate of her own African aesthetics. She is a perfect example of learning from others without losing a sense of self. Her music is wonderfully rich. For example, if you want rock, a la heavy metal, she can and does rock out, but in the same song she will include a djembe or conga drum solo.

Third, I’m impressed by Manou's sturdy bass work. Indeed, I sometimes wish she would push her bass further forward in the mix. Watching the videos you can see how much she’s into playing her instrument and this is also a major development. Comparatively, there are far too few African women who are expert instrumentalists.

Manou Gallo is truly sophisticated. Who would have thought a little barefoot girl who beat on boxes as a child would be producing world-class music firmly situated in the lessons of her childhood? I’ve written at length about Manou Gallo because the other three singers in this roundup have already received far more press than Manou.

Even though I do not speak Dida, I listen closely to Manou Gallo. At the core of her music is an incredibly important and strong sense of self. Back in the day we called it “kujichagulia” (self-determination). We used to say “self” determines the nation, by which we meant, it is our strong sense of self that will be our salvation.

Third, I’m impressed by Manou's sturdy bass work. Indeed, I sometimes wish she would push her bass further forward in the mix. Watching the videos you can see how much she’s into playing her instrument and this is also a major development. Comparatively, there are far too few African women who are expert instrumentalists.

Manou Gallo is truly sophisticated. Who would have thought a little barefoot girl who beat on boxes as a child would be producing world-class music firmly situated in the lessons of her childhood? I’ve written at length about Manou Gallo because the other three singers in this roundup have already received far more press than Manou.

Even though I do not speak Dida, I listen closely to Manou Gallo. At the core of her music is an incredibly important and strong sense of self. Back in the day we called it “kujichagulia” (self-determination). We used to say “self” determines the nation, by which we meant, it is our strong sense of self that will be our salvation.

“The music I wanted to create is a mix of all the steps of my life: my story and my background have inspired me.”

Give thanks to and for women like Manou Gallo. Even in these troubled times their example enables us to be cheerful and optimistic knowing that, guided by a strong sense of self, we can help create a better and more beautiful world.

“The music I wanted to create is a mix of all the steps of my life: my story and my background have inspired me.”

Give thanks to and for women like Manou Gallo. Even in these troubled times their example enables us to be cheerful and optimistic knowing that, guided by a strong sense of self, we can help create a better and more beautiful world.

* * *

2. North. Algeria. Souad Massi. Cross the desert. The language is Arabic, the religion is Islam and the struggle seems indeterminate—who remembers when it started? Who can possibly predict its ending?

At one time Algeria was a beacon of revolution. Franz Fanon was sent there by the French to do psychiatric work—he joined the revolution and became world recognized as a leading theorist of the struggle. Some even referred to his book, The Wretched of The Earth, as the bible of the revolution. The Battle Of Algiers, the Academy Award-winning 1966 movie directed by Gillo Pontecorvo is considered not only a classic of revolutionary cinema, it is also perpetually included on critic’s list of best films of all time. In the seventies some of the Black Panthers went into exile in Algeria. But then the center could not hold and a major civil war erupted, a war which at varying levels of intensity continues today. Souad Massi grew up in Algeria. She lives in France today.

In exile, too often, the wounds never fully heal, the scars remain raw. One perpetually dreams of the past.

2. North. Algeria. Souad Massi. Cross the desert. The language is Arabic, the religion is Islam and the struggle seems indeterminate—who remembers when it started? Who can possibly predict its ending?

At one time Algeria was a beacon of revolution. Franz Fanon was sent there by the French to do psychiatric work—he joined the revolution and became world recognized as a leading theorist of the struggle. Some even referred to his book, The Wretched of The Earth, as the bible of the revolution. The Battle Of Algiers, the Academy Award-winning 1966 movie directed by Gillo Pontecorvo is considered not only a classic of revolutionary cinema, it is also perpetually included on critic’s list of best films of all time. In the seventies some of the Black Panthers went into exile in Algeria. But then the center could not hold and a major civil war erupted, a war which at varying levels of intensity continues today. Souad Massi grew up in Algeria. She lives in France today.

In exile, too often, the wounds never fully heal, the scars remain raw. One perpetually dreams of the past.

Each time I return [to Algeria] they look at me as a stranger. I feel their looks. I feel that they don’t know me. They watch what I do. They are curious. And it’s crazy because in France, I am a stranger. And now at home, we are also strangers. We no longer feel at home. For example, our young people are treated as immigrants in France. They are treated as immigrants in the country of their parents [Algeria], and now they are also immigrants in France. This is one of the problems behind the recent disturbances in the neighborhoods of Paris. People are trying to understand what happened. Well, a big part of it is that so many of these young people don’t know where they belong. In France, I have so much opportunity, privilege, good health care, and much more liberty as a woman than I could have in my own country, for example. But on the other side, since leaving Algeria, I have evolved a lot. I have changed. Now, I am looking for middle ground between the life I had in Algeria, and the one I have in France. —Souad MassiSouad seems to have it all. She is a major star in France. Depending on who is making the reference, Souad is often compared to either Joan Baez or Tracy Chapman. She is revered by young Arab women. She was born August 23, 1972 and arrived in France in January of 1999 to participate in a “Women from Algeria” Festival. One thing let to another. Today her music is on the radio, she routinely sells out concerts and has four albums and a DVD. People love the poetry of her music. The beautiful flow of her voice. Her emotionally engaging lyrics which convince rather than confront, invoke empathy rather than outrage. But there is a deep and contradictory core to her outward success. She has a degree in architecture and has both formally and seriously studied music, both classical music and Arab/Andalousian music. In Algeria she sang solo accompanying herself on guitar, and then she joined a flamenco band, and when that didn’t work, she quit music for a moment until her brother pushed her to continue. So she joined a rock band, “Atakor,” which garnered a major following and, at the same time, because of their political stance, the band members received serious death threats. At one point, Souad cut her hair and dressed as a boy to escape persecution. Cilvil war is the ultimate domestic violence and, as always, women are day-to-day victims of the violence. Souad does not play up the details of her background but her Arab audiences know; they recognize her as a frontliner in the fight for freedom from political persecution and the fight for gender equality, a fight which is far from easy in exile. Moreover, the real conundrum is that she has to fight on two fronts. She fights the historic fight against French colonialism and cultural imperialism (particularly when it comes to the cultural arts and to language in particular, the French are historical stalwarts of xenophobia), but beyond that fight and even more confounding are her struggles within her own culture, especially the struggles with religious fundamentalists. The day-to-day battles are unnerving and can cast one into unfathomable despair. Consider what it must feel like to be embraced and feted by one’s literal colonizers and to be the butt of death threats and persecution by one’s own people. To sing about and under these conditions takes the strength of a saint to keep the faith and keep on keeping on.

“I call for an end to war. [“Bladi” is] a completely naïve song, but for an artist that’s the only way to say that you’re against wars, that you’re against all human stupidity, against all forms of oppression that can exist.” —Souad Massi“Amessa” and “Ech Edani” are selected from Live Acoustique 2007, Souad’s CD/DVD release (the audio tracks are available on Acoustic The Best Of Souad Massi). In addition to the seriousness of her back story, I am interested in two other issues. First, Souad sings in Arabic and, second, her live concerts are very different from her studio albums.

Arabic is not only a foreign language to American ears, it is also a language associated with ethnicities and a religion that are deemed to be at odds with American democracy. (Make that American capitalism, whose rapacious free enterprise is the not-so-hidden, but also not fully comprehended, economic enforcer.) Islam is also often assumed to be at odds with America’s de facto official religion of Christianity. Moreover, the very sound of the language is totally different from the Romance languages not only in script but also in pronunciation. The Arab tongue does things the Romance tongue doesn’t and vice versa.

All these divides notwithstanding, Souad’s music bridges cultures and promotes at the very least a curiosity about, if not a full blown appreciation of, Arab/Islamic culture.

Arabic is not only a foreign language to American ears, it is also a language associated with ethnicities and a religion that are deemed to be at odds with American democracy. (Make that American capitalism, whose rapacious free enterprise is the not-so-hidden, but also not fully comprehended, economic enforcer.) Islam is also often assumed to be at odds with America’s de facto official religion of Christianity. Moreover, the very sound of the language is totally different from the Romance languages not only in script but also in pronunciation. The Arab tongue does things the Romance tongue doesn’t and vice versa.

All these divides notwithstanding, Souad’s music bridges cultures and promotes at the very least a curiosity about, if not a full blown appreciation of, Arab/Islamic culture.

It’s true that there is a disconnect between me when I sing on a CD and when I sing on the stage. On the stage, I am happy. I love being on stage. I love the contact with people. That makes me happy. When I am writing songs for an album, it’s not the same thing at all. —Souad Massi

Listening to these songs in concert, one can easily understand that there is a spiritual core, not just in terms of the meaning of the words but also in terms of the trance/transformative power of Souad’s music. The drumming, the audience participation, the length of the songs—it all encourages one to lose oneself in the music, and in losing the public self, Souad encourages us to find the inner self.

Perhaps it is all the contradictions she has had to deal with that gives her music such a sharp edge, such a serious core. Without understanding one word, it is clear this is serious music.

Listening to these songs in concert, one can easily understand that there is a spiritual core, not just in terms of the meaning of the words but also in terms of the trance/transformative power of Souad’s music. The drumming, the audience participation, the length of the songs—it all encourages one to lose oneself in the music, and in losing the public self, Souad encourages us to find the inner self.

Perhaps it is all the contradictions she has had to deal with that gives her music such a sharp edge, such a serious core. Without understanding one word, it is clear this is serious music.

* * *

3. East. Somalia. Saba Anglana. With a degree in Art History from the University of Rome La Sapienza and a major career as a star on Italian television, Saba might seem like the last person to be featured in a survey of contemporary African music.

I acknowledge my initial reaction: my eyes made it difficult to appreciate what my ears were hearing. Or, to put it more bluntly, I could not help but identify with jazz man Archie Shepp’s acidic comment about trombonist Roswell Rudd (a white man who later became a member of Shepp’s band in the sixties): I liked your music better before I saw you.

3. East. Somalia. Saba Anglana. With a degree in Art History from the University of Rome La Sapienza and a major career as a star on Italian television, Saba might seem like the last person to be featured in a survey of contemporary African music.

I acknowledge my initial reaction: my eyes made it difficult to appreciate what my ears were hearing. Or, to put it more bluntly, I could not help but identify with jazz man Archie Shepp’s acidic comment about trombonist Roswell Rudd (a white man who later became a member of Shepp’s band in the sixties): I liked your music better before I saw you.

I had to face, very early in my life, this problem of identity ... since I was a child, I had to learn very quickly to define my identity. And I found out that my identity is not something given, I mean something that cannot change. It's something that changes day by day. It's a matter of growing and growing from the human point of view. —Saba AnglanaSaba pushes a lot of emotional buttons. Once I hit on the idea of choosing a singer from each of the four corners of Africa I found myself conflicted about including Saba. Wasn’t there a darker sister who deserved to be highlighted, someone who is not getting all the international press—and so forth and so on. It does not take much imagination to appreciate some of the conflicts I was feeling. But again, like Shepp, if we are serious, we struggle to get over our own prejudices and try to open our ears (and hopefully our minds, hearts and total beings) to the other. In the long run it is important not only to recognize our common humanity with others, it is equally important to recognize and embrace the most profound paradox of human existence: we put a lot of weight on our self-identity, but none of us chooses our birth histories or legacies. That said, by being born we all have an opportunity (and some would say a responsibility) to face ourselves and hopefully not only accept the truths of our history and conditions but also extend ourselves beyond the been here and gone, beyond the here and now. Although we may not know the future, we can certainly help shape the future and a major part of shaping our future is shaping ourselves to be more than we were in the past, more than we are in the present. Saba Anglana struggles with this even as her music causes us to struggle with our own perceptions of African music. Africa is deep, deeper than any stereotype. The continent and its people are iconic of any aspect of humanity one might explore. Even the word “explore” has a stereotypical connotation in the African context not the least of which is the issue of “race” contrasted with the characterization of Africa as the dark, unknown (and some would say, unknowable) continent. Saba is an African separated from herself who is using her music to perform open heart surgery and emotionally suture together aspects that have been forced asunder.

Nothing is so easy to do, but music and art in general are a good way to let us free ourselves to understand our nature as hybrid people. I wanted to be free. I wanted to speak about my way of learning to a culture but not only one. I don't feel Italian. I don't feel Somalian. I feel all these things together. When I speak to Italian people, they don't think I'm Italian, and the same with Somalian people. I tried through music to express this feeling and this problem. —Saba AnglanaAgain we confront the issue of language. Although she is not only an actress but also a published author, Saba has found in music a way to express herself that she did not find in any other way.

I'd always thought to sing in Italian or English, because I always heard music from the States and England. But at some point I tried to put the lyrics in Somali, just because of the beauty and the power of the sound. It was sort of an experiment. And from that time on I felt something very true was going on. I was free, setting myself free. I found out it was a way to speak about my identity for the very first time in my life. I'm not telling you I belong to Somali culture, but I have memories of my childhood and a part of my way of living was coming from where I was born, from Africa, where my father and mother wanted to be together and merge their cultures. So it was sort of a tribute to my childhood and my father and mother's loving country. —Saba Anglana

The back story is both simple and complex. Her father, a former colonel in the Italian military, went to Somalia (which had been a colony of Italy) to live out the rest of his life after the horrors of World War II. Saba’s maternal grandfather had been captured while fighting in Ethiopia against the Italian invasion and had been deported to Somalia where he continued to reside after the war. Although of Ethiopian heritage, Saba’s mother was born in Mogadishu, Somali’s capital city.

Saba’s parents met in Mogadishu, fell in love, gave birth to two daughters, and five years after Saba was born, the Somalian government of General Muhammad Siyad Barre gave her family 48 hours to leave Somalia or else… End of story, beginning of story. Although she visited her maternal relatives in Ethiopia (Saba’s mother lives with Saba in Rome), Saba never returned to Somalia.

The back story is both simple and complex. Her father, a former colonel in the Italian military, went to Somalia (which had been a colony of Italy) to live out the rest of his life after the horrors of World War II. Saba’s maternal grandfather had been captured while fighting in Ethiopia against the Italian invasion and had been deported to Somalia where he continued to reside after the war. Although of Ethiopian heritage, Saba’s mother was born in Mogadishu, Somali’s capital city.

Saba’s parents met in Mogadishu, fell in love, gave birth to two daughters, and five years after Saba was born, the Somalian government of General Muhammad Siyad Barre gave her family 48 hours to leave Somalia or else… End of story, beginning of story. Although she visited her maternal relatives in Ethiopia (Saba’s mother lives with Saba in Rome), Saba never returned to Somalia.

We were a mixed-marriage family: inconvenient, perhaps a threat. I still remember nights at Bolimog (Cape Guardafui, near Alula — the extreme east point of Africa, where my father was working) when policemen came to interrogate my father, as they thought he was a US spy. In reality, he was there because he loved Africa, and my sister and I were born there. —SabaToday, Somalia is sometimes sneeringly and dismissively returned to as a basket case albeit an extremely dangerous basket case. Ships bearing food and medical supplies have subject to waves of speedboat pirate attacks, aid workers have been assassinated; hell, Hollywood made a whole action movie called Blackhawk Down, referring to an infamous incident in which a covert U.S. military operation in Mogadishu went disastrously awry resulting in not only death but also international humiliation for America’s armed forces. Over a thousand Somolians died during the battle and the bodies of dead American soldiers were dragged through the streets. The light of hope for Somalia has been all but extinguished: is this the Somalia that Saba sings of? Yes and no.

Africa in general has a strong power. From one side, it has a sweet power, a joyful power. And the other side is a sort of dramatic power, violence. And these two things, opposite things, are living together. And, of course, it's very striking. I remember [Mogadishu] was a joyful place where to live, and I wanted to record this positive side. Because we don't think, we have to think about Africa speaking about only the negative sides, and the poverty, and the diseases, and all this kind of thing. But we are witness of this good way of living in Africa. It could be possible. I mean, I hope now that the situation could get better. —Saba AnglanaAnd here is the conundrum: should we celebrate or be suspicious of Saba’s music, Saba’s choice to record in Somali, historically her mother tongue but in practice a language she knows at arm’s length and that she learned informally but consciously from her mother.

I didn’t care about the grammatical correctness — the aim was to let my memories flow and to translate them into the other language very close to me: music. [My music] reminds me of the songs I heard when I was little and recalls a lost world. I wrote some of the lyrics with my mother. The Somali language gives me great satisfaction for the musical and expressionistic sound of the words, but, more than anything else, for the value this reunion represents in my human growth. It feels like I’m moving closer to a part of me that lives in the woman that gave me life: my mother. In the evenings (as she did with her sisters and brothers around the fire), we rediscovered the pleasure of storytelling and I’d fight against her shyness to get her to speak in Somali. Like many people, we were never able to go back to Somalia. This is my return. —Saba AnglanaWho am I to doubt the sincerity of Saba’s music? On the other hand, Jidka immediately strikes the ear as a polished, professional album. How much is memory, how much is Memorex? On the Italian television cop-series “La Squadra,” Saba plays the part of a cop who is half-Italian, half-African. How much is type-casting: Saba simply being herself while acting like someone else, and how much is acting: Saba donning a mask she intimately knows—and is it even possible to separate the two? Musically, part of me recoils from the slickly polished “pop” elements, from some of the sights and sounds of her videos, sights and sounds which are premeditated if not out and out contrived but then behind the façade there is a reality and a powerful pulse that I respond to. Saba’s band exemplifies my ambivalence.

On Saba’s website the above-pictured band members are described—

On Saba’s website the above-pictured band members are described—

From the left: Cheikh Fall, from Senegal, kora and djembè; he is a young and talented musician, percussions teacher, also playing in the Orchestra of "Piazza di Caricamento." Salvio Vassallo, from Naples, drums; musician of great experience, he was the motor nerve of the well known band Spaccanapoli. Tatè Nsongan, from Cameroon, guitar and djembè; he is a long term element of Mau Mau. He is the author of many works focused on the cultural exchanges (among all, the album Etnokult published by Il Manifesto). Fabio Barovero, keyboards; the producer of Jidka, movie sountracks composer, founder of Mau Mau, producer and author of Banda Ionica, one of the cult-projects of World Music in the last years. Martino Roberts, bass; refined musician half italian and half American, working in Paris, gold medal at the International Music School of Montreuil.Undoubtedly, Fabio Barovero, the keyboard player and co-producer with Saba of her debut album, had a major hand in developing Jidka’s sound but to my ears the most interesting element is the contribution of guitarist and backing vocalist Tate Nsongan. His steady on guitar and quietly passionate vocals give heft to a pop sound that could easily have fizzed off into (we are the) world music never-never land. Tate is both the anchor and the pendulum.

Tate grounds the music in an Africa flavor and at the same time keeps swinging time. The way their voices work together is beyond interesting, indeed, at first blush why would Tate’s near-solemn baritone and falsetto asides merge so smoothly with Saba’s high-pitched tones that sometimes verge on (but thankfully never quite cross the line into) what I will sarcastically call the faux-soul of the “white girl whine.” (Yes, I said it, and in saying it the most important thing to recognize is that it says far, far more about my own tastes and my own prejudices than it does about Saba’s singing.)

Saba’s music is a real acid test. Part of it is real and part of it tests me. I wear my ambivalence openly, I both embrace parts and reject parts. I would have used a lot less synths and a lot more kora but then again, it’s not my album.

My duly noted reservations not withstanding, there is an essential truth: this is far, far from a Somali band, indeed, the lyrics include Italian, English, Hebrew atop Saba’s rudimentary Somali. In one sense Jidka is almost amateur or worse yet, a multicultural band put together in some global capitalism’s marketing department.

But, ah, the genuine moments of both brilliance and openly bared, vulnerable emotions. Although the general sound is bright and breezy, the actual meaning of the songs is anything but—here is a case where not understanding the words actually helps one get into the music. On the surface: pop; beneath the surface: profundity.

Saba's website includes a loose translation of the four songs (“Furah,” “Hoio,” “I Sogni” and “Yenne Yenne”) included in the BoL jukebox. Check out the lyrics, you will be surprised.

Saba's debut album, Jidka, is the cultural jumble that is contemporary Africa. Like it or not, Saba’s music perfectly exemplifies major issues that Africa is being force to sort out. Jidka (The Line) is Saba’s high wire attempt to cross borders and unite opposites. To be continued.

Tate grounds the music in an Africa flavor and at the same time keeps swinging time. The way their voices work together is beyond interesting, indeed, at first blush why would Tate’s near-solemn baritone and falsetto asides merge so smoothly with Saba’s high-pitched tones that sometimes verge on (but thankfully never quite cross the line into) what I will sarcastically call the faux-soul of the “white girl whine.” (Yes, I said it, and in saying it the most important thing to recognize is that it says far, far more about my own tastes and my own prejudices than it does about Saba’s singing.)

Saba’s music is a real acid test. Part of it is real and part of it tests me. I wear my ambivalence openly, I both embrace parts and reject parts. I would have used a lot less synths and a lot more kora but then again, it’s not my album.

My duly noted reservations not withstanding, there is an essential truth: this is far, far from a Somali band, indeed, the lyrics include Italian, English, Hebrew atop Saba’s rudimentary Somali. In one sense Jidka is almost amateur or worse yet, a multicultural band put together in some global capitalism’s marketing department.

But, ah, the genuine moments of both brilliance and openly bared, vulnerable emotions. Although the general sound is bright and breezy, the actual meaning of the songs is anything but—here is a case where not understanding the words actually helps one get into the music. On the surface: pop; beneath the surface: profundity.

Saba's website includes a loose translation of the four songs (“Furah,” “Hoio,” “I Sogni” and “Yenne Yenne”) included in the BoL jukebox. Check out the lyrics, you will be surprised.

Saba's debut album, Jidka, is the cultural jumble that is contemporary Africa. Like it or not, Saba’s music perfectly exemplifies major issues that Africa is being force to sort out. Jidka (The Line) is Saba’s high wire attempt to cross borders and unite opposites. To be continued.

* * *

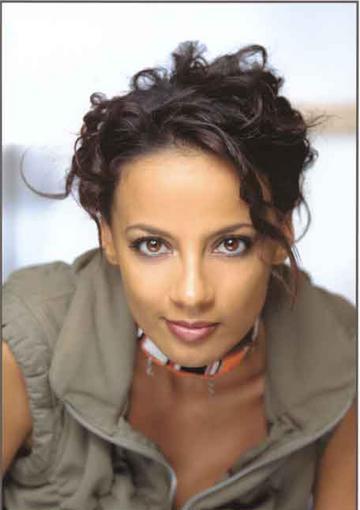

4. South. South Africa. Ernestine Deane—they call her Earnie. If you are African-American (of the USA variety), as soon as you hear her, you know. No explanation necessary. Earnie’s sound is an instant connect.

And like Manou, Souad and Saba, Ernestine Deane’s music runs far, far deeper than the surface seems to promise. Apartheid had classified Ernie as colored. She rejects that particular politicization of skin color and simply refers to herself as “brown.”

In their own way, each of these four women are seriously investigating identity issues. In the interest of healing, they don’t merely finger the wound. They musically scrub off dirt-encrusted scabs, lance boils, release pus and other toxins, apply medicinal potions, and resultantly cleanse and expose their private and personal wounds to the antiseptic of public sunlight.

Because she sings in English, the political content of Ernie’s music is much more evident to many of us in the diaspora; and because Ernie’s stylistic preferences include jazz, gospel, reggae, hip-hop and R&B, her music is not only accessible but extremely attractive, except that her lyrics are consciously confrontational, almost severe in the oppositional stances she stakes out.

Although none of the four women make lush or highly ornamented music, Ernie’s backing is almost stark in comparison. Her voice is pushed way forward and, with the exception of sensitive sax or flute obbligatoes (particularly on "Brown" and "Think Again"), the backing instrumentation is spare. While the musical accompaniment is minimal, the backing vocal tracks are almost as strong as the music. Ernie layers and overdubs her voice, weaving a vocal tapestry that is both subtle and omnipresent. But why try to describe the beauty of her sounds when the sounds speak so eloquently for themselves.

Ernie's October 2006 debut solo album, Dub For Mama, attains the level of serious Black music, a level both futuristic and ancestral. This is music not only appropriate for all ages, this is music for all the ages/eras that our people have seen, now see, and will see. Seen?

I am particularly impressed by the feature track "Prayer For Cape Town" (which is a variation on "Amazing Grace") and by the Yemanya-channeling of "Watersong."

But beyond the music itself, I relate to Ernie’s process of music making. Dub For Mama is not only a conscious statement about identity and ecology, it is also an assertion of political and economic self-determination.

4. South. South Africa. Ernestine Deane—they call her Earnie. If you are African-American (of the USA variety), as soon as you hear her, you know. No explanation necessary. Earnie’s sound is an instant connect.

And like Manou, Souad and Saba, Ernestine Deane’s music runs far, far deeper than the surface seems to promise. Apartheid had classified Ernie as colored. She rejects that particular politicization of skin color and simply refers to herself as “brown.”

In their own way, each of these four women are seriously investigating identity issues. In the interest of healing, they don’t merely finger the wound. They musically scrub off dirt-encrusted scabs, lance boils, release pus and other toxins, apply medicinal potions, and resultantly cleanse and expose their private and personal wounds to the antiseptic of public sunlight.

Because she sings in English, the political content of Ernie’s music is much more evident to many of us in the diaspora; and because Ernie’s stylistic preferences include jazz, gospel, reggae, hip-hop and R&B, her music is not only accessible but extremely attractive, except that her lyrics are consciously confrontational, almost severe in the oppositional stances she stakes out.

Although none of the four women make lush or highly ornamented music, Ernie’s backing is almost stark in comparison. Her voice is pushed way forward and, with the exception of sensitive sax or flute obbligatoes (particularly on "Brown" and "Think Again"), the backing instrumentation is spare. While the musical accompaniment is minimal, the backing vocal tracks are almost as strong as the music. Ernie layers and overdubs her voice, weaving a vocal tapestry that is both subtle and omnipresent. But why try to describe the beauty of her sounds when the sounds speak so eloquently for themselves.

Ernie's October 2006 debut solo album, Dub For Mama, attains the level of serious Black music, a level both futuristic and ancestral. This is music not only appropriate for all ages, this is music for all the ages/eras that our people have seen, now see, and will see. Seen?

I am particularly impressed by the feature track "Prayer For Cape Town" (which is a variation on "Amazing Grace") and by the Yemanya-channeling of "Watersong."

But beyond the music itself, I relate to Ernie’s process of music making. Dub For Mama is not only a conscious statement about identity and ecology, it is also an assertion of political and economic self-determination.

Born in 1972, Ernie grew up on the Cape Flats in Grassy Park, Cape Town, South Africa. (Cape Town is located on the lower tip of Africa where the Indian Ocean meets the Atlantic Ocean.) Her professional life as a singer started when she was fifteen working with the hip-hop crew Black Noise. A few years later she made her mark in South Africa as the lead vocalist for Moodphase5ive with whom she released two albums: Steady On and In Superdeluxe Mode. In April 2001, “Uneek,” a Moodphase5ive single, held down the number one spot on the radio charts for three consecutive weeks.

Her benchmark year of development was 2002 during which she undertook an exploratory documentary about her family history and became pregnant for the first time. Her pregnancy became part of the documentary’s focus. The documentary is simply called Brown.

Brown was co-produced by the South African media group Other-Wise and directed by Kali van der Merwe. “Other-Wise media is an association for non-profit established in 1996. Our aim is to produce awareness-raising, engaging and entertaining media on topics that are misrepresented or absent in mainstream media, creating a voice for those who are least heard.” A synopsis on the Other-Wise website states:

Born in 1972, Ernie grew up on the Cape Flats in Grassy Park, Cape Town, South Africa. (Cape Town is located on the lower tip of Africa where the Indian Ocean meets the Atlantic Ocean.) Her professional life as a singer started when she was fifteen working with the hip-hop crew Black Noise. A few years later she made her mark in South Africa as the lead vocalist for Moodphase5ive with whom she released two albums: Steady On and In Superdeluxe Mode. In April 2001, “Uneek,” a Moodphase5ive single, held down the number one spot on the radio charts for three consecutive weeks.

Her benchmark year of development was 2002 during which she undertook an exploratory documentary about her family history and became pregnant for the first time. Her pregnancy became part of the documentary’s focus. The documentary is simply called Brown.

Brown was co-produced by the South African media group Other-Wise and directed by Kali van der Merwe. “Other-Wise media is an association for non-profit established in 1996. Our aim is to produce awareness-raising, engaging and entertaining media on topics that are misrepresented or absent in mainstream media, creating a voice for those who are least heard.” A synopsis on the Other-Wise website states:

As she embraces motherhood, Capetonian singer/songwriter Ernestine Deane embarks on an enquiry into her heritage. In the 1960s under the infamous Group Areas Act, her Grandparents were evicted from their functioning farm in Constantia, and relocated to the urban suburb of Grassy Park. Integrally wedded to the land, her grandfather continues to yearn for the tract that remains fallow and unused in one of the most exclusive suburbs of Cape Town. Their return visit unleashes the suppressed emotion resulting from years of marginalisation and loss. This touching and deeply personal journey investigates the past with the intention of celebrating a new community, new nation, and new family. By exploring her past and her present, it carries Ernestine from emotional remembrance to musical realisation and celebration, culminating in the song, Brown.Three important threads in the documentary are: her family history, her personal/social identity and her pregnancy. As noted on her company’s MySpace page, Ernestine “hosts community workshops using the film ‘Brown’ as a tool to encourage men, women and youth to find their creative expression and explore their heritage.” In 2003 she had a feature role in the South African film Boy Called Twist, which was a South African take on Dickens’ classic Oliver Twist. In addition to acting Deane also sang and contributed original music for the film score.

A recent development is the theatrical collaboration Womantide. Working with singer/songwriter Tina Schouw and performance poet Malika Ndlovu, the three women weave music and poetry to produce a production that focuses on the feminine “in honour of the human spirit.”

Under the banner “healing through creativity” Ernestine’s main work is Konshus Pilot which is also the label for Dub For Mama. The website description is:

A recent development is the theatrical collaboration Womantide. Working with singer/songwriter Tina Schouw and performance poet Malika Ndlovu, the three women weave music and poetry to produce a production that focuses on the feminine “in honour of the human spirit.”

Under the banner “healing through creativity” Ernestine’s main work is Konshus Pilot which is also the label for Dub For Mama. The website description is:

Though it was founded in 2005, the business has been formally operating since January 2007.

The business is a multimedia company trading in intellectual property. Konshus Pilot promotes the age-old African practice of story telling through the medium of music and film, acting as a record label and film production company. The company only deals with conscious local content i.e. music and films that promote belief systems, heritage and identity. Konshus Pilot makes these formats available to disadvantaged communities, (particularly women and youth), via workshops, open day functions and motivational speaking. Konshus Pilot publishes music and distributes music and film content to the mainstream distribution and promotion networks i.e. retail stores, radio, television and the internet. The company also licenses music for film scores, soundtracks and advertising.

The main obective of Konshus Pilot is to bring the music and film products directly to the disadvantaged communities who can best benefit from their uplifting content.

Konshus Pilot is a Cape Town based multimedia company that promotes modern-day storytelling with conscious content, through the media of music and film, making it accessible to communities via the ‘Brown’ workshops, beyond the mainstream distribution network of broadcasters and retail stores. Konshus Pilot deals only in original content that promotes pride in heritage and identity as well as ‘healing through creativity’. The company is aware of the huge impact of music and film on South African youth, particularly those in disadvantaged communities. Konshus Pilot is committed to producing content that instills in the youth a pride in their South African identity, encouraging these communities to embrace and tell their own stories rather than looking abroad for role models who offer no real upliftment beyond the façade of glamour they portray.

Konshus Pilot is owned and managed by the creative husband and wife team, Brian de Goede and Ernestine DeaneA lot of artists claim individual ownership but too often it is solely for the purpose of individual aggrandizement and has nothing to do with community development. Obviously I think this effort is key to not only our development as human beings but also to the development of the music. When our art is viewed strictly as entertainment and/or commerce, the quality of the art is diminished and the value to the community is lost.

Ernestine Deane’s vision of collective and community-based development is extremely difficult to sustain in the era of global capitalism, and it is particularly difficult in the new South Africa that has yet to resolve a number of old problems; color conflicts and access to resources based on social class and racial caste increasingly looms as a central contradiction manifesting itself in a myriad of manners including high rates of crime and AIDS, persistent poverty and violent xenophobia.

Stand firm sister Deane. Keep pushing that subtly nuanced and simultaneously politically conscious music you are making, that community you are healing and constructing. Your work is hugely appreciated. On the one level your efforts are personal, based on your own decisions within your particular circumstances, but on another level your work is emblematic, exemplary of the work that all conscious elements must do. We must seek, identify, collect and nurture ourselves if we are to have any future worth living.

Ernestine Deane’s vision of collective and community-based development is extremely difficult to sustain in the era of global capitalism, and it is particularly difficult in the new South Africa that has yet to resolve a number of old problems; color conflicts and access to resources based on social class and racial caste increasingly looms as a central contradiction manifesting itself in a myriad of manners including high rates of crime and AIDS, persistent poverty and violent xenophobia.

Stand firm sister Deane. Keep pushing that subtly nuanced and simultaneously politically conscious music you are making, that community you are healing and constructing. Your work is hugely appreciated. On the one level your efforts are personal, based on your own decisions within your particular circumstances, but on another level your work is emblematic, exemplary of the work that all conscious elements must do. We must seek, identify, collect and nurture ourselves if we are to have any future worth living.

* * *

While it make seem that I have loaded a lot of sociological baggage on this musical train circling the perimeter of mother Africa, the essential two-part inner truth is that 1. As bitter as they may be, issues of identify and inequality are major issues of the day and 2. The best of our music has always, always dealt with these issues, precisely because the best of our music is the best of our selves and we are at our best when we are being (or struggling to be) our true selves.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Vastness of Africa OK, that was an epic overview. Where do I even begin? I guess at the beginning. So first off, I’m fairly certain I saw Manou perform with Zap Mama. I think it says a lot about her as an artist that even though she played as part of Marie Dualne’s band for that long, she has still come up with her own sound. Every once in a while I hear a little of the Zap Mama vibe in the way the vocals are layered, but overall, Manou’s doing her own thing. I really, really like what I hear. I’m into rhythms, first and foremost, and Manou’s music has a lot going on rhythmically. Even in the quiet segments of songs like "Pôlyne," there are still polyrhythms working. I particularly like the way the background vocalists sometimes sing melodies and sometimes do a rhythm thing with their voices. This is very good music. Forward-sounding and authentically modern while still sounding in touch with tradition. I dig it a lot. I like Manou’s music more, but if we’re going on voices alone, I’ll take Souad. What a voice! I posted a track from her before and it was all based on that lilting sound she has. It’s an angel-sweet overtone with a bitter undertone that serves to keep her from ever sounding too sugary. Unlike Kalamu (and Souad herself, apparently) I prefer her studio work to these live tracks, but I am happy to hear that she’s just as strong a singer live as she is on record. I want to say too, that I know what Kalamu means about the Arabic thing. I usually don’t like hearing people sing in either Arabic or German - both languages sound very guttural to me, meaning, not at all melodic. But when someone sings well enough, it really doesn’t matter. Souad’s Arabic is beautiful. I actually like it more than when she sings in French. A lot of mixed (no pun) feelings about Saba, huh? I don’t have any mixed feelings about her lifestyle or racial heritage or sound or anything. Honestly, I don’t have a clue as to how authentic or inauthentic her Somali is. How would I know? Strangely enough, one of her songs, "Furah," is my favorite out of all of the songs Kalamu posted (by all four of the artists, I mean). The other three aren’t really doing it for me. Why? I dunno. The other ones have a sort of repetive sound, rhythmically. They sound a little too "easy," I guess. "Furah" is a great record though. I’ve listened to that one about about ten times in the last two days. Before I say anything about Ernestine Deane, I want to comment about the breadth of these sounds. I’ve mentioned before that we have a tendency to think of Africa as though it’s a single, quantifiable "thing." Of course, it’s anything but. It’s a vast, vast continent; in some ways, it’s silly to even talk about "African music." I mean, really - listen to these four singers. All four are young, progressive, attractive female singer-songwriters of African ancestry. Sounds like a lot of similarities, right? Except that their music sounds nothing alike. Even if you have no interest in African music, I think you can easily hear the difference in these styles of singing and playing. So that’s that - the vastness of Africa and African music. So, Ernestine. I have to give Ernestine the nod as the most polished and balanced performer. She clearly knows what she’s doing, what she wants to express, how she wants to sound, how she wants to be heard. That’s not a qualitative statement. I mean, I’m not saying she’s "better" than the other three singers; I’m saying she sounds further along on her chosen musical road. I know why Kalamu picked "Prayer For Cape Town" as the feature. It has that emotional depth and is also easy on the ears. I like it. I like "Brown" too - good groove. And "Water." It’s a little ponderous, but I think I could eventually get past that and really like it. She’s a talent. The last thing I want to say before we wrap up what must surely be the longest single post in the history of blogging itself is about Ernestine’s vibe. She sounds like she lives close to the sea. Before I knew who she was (or even knew her name or where she was from), I asked Kalamu whether or not she was from an island country. He told me no, but she was from a town that was right on the water, near the intersection of two oceans. I wasn’t surprised. There’s this melancholic, slightly morbid (I can’t think of a better word) vibe to her sound. She sounds like New Zealand singers and Icelandic singers and some Jamaican singers. Like they’re floating down into the depths and don’t really care whether or not they drown. I’m not saying they sound similar to one another and I’m not even sure I’m making sense, but there’s a certain sadness that ocean people seem to have. I don’t know what that’s about. —Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Monday, July 21st, 2008 at 12:01 pm and is filed under Contemporary. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |