CHEIKH LO / “Bambay Gueej”

“[Afro-Cuban music] was my school. I never had the chance to go to school a more how to play the drums, or the guitar, or anything like that. Where we received our schooling was through listening, lots of listening. And the impression from listening to Cuban music was strong, and stayed within us, like an imprint. You can't erase it. I think it's also a return to sources for the Cubans. They left with that. They left Africa, and they took something with them. And in listening, we sense that. Maybe we learned in school who the Cubans are, so that we would know the history. But we could sense it right away, by listening.”

—Cheikh Lo

Bumblebee time! Last week I dropped the theory of black musical pollination to help explain and understand influences, exchanges and developments found in contemporary Black music both on the continent and in the diaspora (and beyond: think New Zealand). Well, Cheikh Lo is King Bumblebee. This man is a synergistic phenomenon. But before we study up on his flights of imagination, let’s look at the groundwork that was laid before him.

There is an album called African Salsa: Senegalese Salsa Fireworks and it features a number of Senagelese musicians who mixed Senegalese forms with Afro-Cuban Salsa. It’s mind-blowing to hear these grooves. It sounds like Spanish Harlem or Habana on a hot night but the supple voices are not shouting out in Spanish. It’s wild. There’s a refreshing tingle to it—sort of like the difference between quality mineral water and distilled water; it’s water but the trace elements give the mineral water a little extra kick.

Since the late forties, Cuban music has been popular throughout West and Central Africa and especially in the Congo (were they developed Soukous) and Cameroon (where they came up with Makossa). In Senegal, they came up with Mbalax, a style that was drum heavy and incorporated elements of popular music from abroad including Afro-Cuban, Funk and Soul, and later Hip Hop.

Pape Fall is the man who is considered one of the founding fathers of African Salsa in Senegal. I can’t say for sure he started it because I don’t know enough but I know he’s got a dance floor flow that won’t quit. Fall has half of the 14 tracks on African Salsa.

When I was getting into some Afro-Cuban music I ran into a group called Africando, dug it and duly added it to the collection without knowing one thing about the music except it was a little different. Turns out Africando is a concept group. In 1990, music producer Ibrahim Sylla from the Ivory Coast and arranger Boncana Maiga (of the New York-based Fania All Stars) originally from Mali came up with the idea to combine Salsa players based in New York with vocalists from Senegal.

Africando was a huge success and over the years vocalists from other West African countries were added. Salif Keita even did a short stint with the group that was then known as Africando All Stars. Again, I don’t know enough to tell you who is singing on which tracks but I know enough to know these jams are astoundingly beautiful. At some point I suppose I should do some research and do a full write-up on Africando. They are a significant development in the music. Africando has one cut on African Salsa.

African Salsa is absolutely a great starting point. Highly recommended.

* * *

At this point it is important to me that I make sure folks don't miss the political undercurrent to the Afro-Cuban connection. Musically, Africando came out of New York City, not Havana. Cuba is under heavy American embargo. It's difficult for Cuban musicians to participate in USA-based projects even as Afro-Cuban styles and aesthetics defiantly cross embargo barriers. Plus, Puerto Ricans, with their own history of African rhythms and retentions, are able to participate without embargo restrictions.

In Senegal, and throughout Africa, the situation vis-a-vis Cuba is the exact opposite of the USA embargo. Most Africans are proud of Cuba and grateful for Cuban medical and military assistance, particularly when Cuba sent fighters to Angola to share the struggle against apartheid South African soldiers who were then marching on Angola. We in the United States are generally ignorant of Cuba's political role in Africa but Africans aren't. Thus the popularity of Cuban music is not simply or solely an aesthetic popularity.

* * *

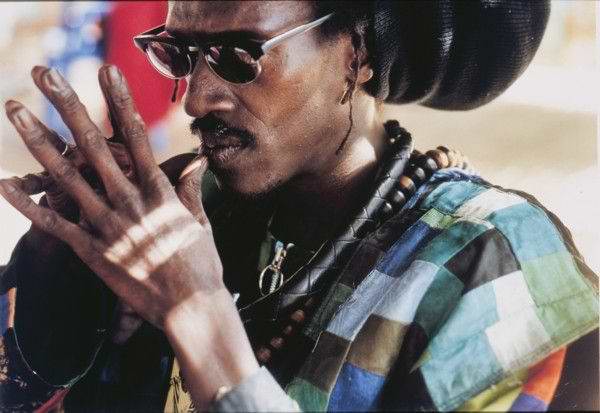

So that was some of the atmosphere within which Cheikh Lô came to musical maturity. He started off as a drummer in various bands and only later picked up a guitar and began to compose his own songs. He is considered one of the most serious of African artists. Cheikh is a Baye Fall, a Senegalese Sufi order of Islam. The spiritual element is essential to Cheikh’s music.

Undoubtedly Cheikh’s personal background shaped him to be open to the world and not to fear incorporating outside influences. He was born of Senagelese parents in Burkino Faso and, the son of a jeweler, he was reared in a home that was at the cross roads for numerous people passing through the region.

"There were Toucouleur there. There were Malians passing through. Every day, people came and people went. Sometimes, there were thirty people in our home."

—Cheikh Lo

Lô moved to Senegal in 1978 to pursue a career in music.

According to National Geographic World Music website, Lô's recording debut, Doxandeme (Immigrants), was released as a cassette in 1990. Doxandeme brought him some notoriety.

Lô also spent a couple of years working in Paris during his period of development. After opening for Youssou N’Dour on a European tour, Lô and N’Dour returned and produced Cheikh’s noted 1997 debut.

Cheikh works slowly, taking years to produce an album and it pays off. Each of his works are sonic gemstones. Ne La Thiass (1996), Lô’s debut CD/LP was produced by Youssou N’dour. Thiass has a quietly spiritual acoustic vibe that is a gumbo of influences, so many different elements mashed together into one uniquely intoxicating taste. In 1996, Ne La Thiass won the European Music Journalists’ prize for Best World Music Album.

Bambay Gueej (2000), Lô’s second album, represents Cheikh Lô filtering the major influences on contemporary Senegalese music into one astounding presentation. This time Youssou is a co-producer.

One minute it’s Salsa (“M’Beddemi"), the next it’s funk (“Bambay Gueej”)—that’s James Brown’s Pee Wee Ellis arranging the horns—and the next minute Cheikh is doing something that sounds almost like a combination of Central American folk music and West African griot storytelling with a hint of reggae ("N’Dokh”). The way Cheikh mixes the influences it’s impossible to totally separate one element from another.

Note that on “Bambay Gueej” there is not only a strong James Brown element in the mix, Lô also literally incorporates Fela Kuti’s “African Woman” into the song. Fela’s Afro-Beat music is heavily influenced by James Brown. “Bambay Gueej” is a double genuflect to the twin manifestations of the bomb: funk on the American side of the Atlantic and Afro-Beat on the black hand side.

Lô’s third album Lamp Fall (2005) raised the ante again. Cheikh had been working on the album for years but was not satisfied with what he had. This was not the first time he refused to release music because he did not think it was fully developed.

After the good reception to his first cassette, he worked on a second cassette for the Dakar market but declined to release it. Lô is a thoughtful, serious musician who intends to make every release a meaningful step forward. For those intent on hearing early Lô, both cassette recordings are contained on the 1999 album titled Inedits.

Inedits sounds on the one hand like ordinary African pop—synthesizers and all—on the other you can hear Lô’s strong lead vocals and his interest in different styles of music. It’s not bad but it is not even a shadow of what Cheick Lô would produce afterwards.

To complete the post-production on Lamp Fall Cheikh Lô decided to go to Brazil where he hooked up with Carlinhos Brown.

“Carlinhos’s studio is there in the neighborhood. And the young musicians he works with, they play those big drums with sticks. I said to myself, This is almost Africa. Effectively, this is Africa. Because they themselves were transported from Dakar-Gore to wind up in Brazil.”

—Cheikh Lo

So yes, that is a berimbau (a bowed Brazilian percussion instrument) and an accordion on “Keile Magni.”

“Fattaliku Demb” has so many different rhythms working, if you weren’t raised on some of this stuff, you’d have to have jackrabbit instincts to follow its twists, turns, shifts and reverses. Moreover, it’s not just rhythms. The harmony moves as well—I bet you this is some of what Ornette Coleman was aiming for with harmolodics.

The title cut, “Lamp Fall,” comes at you in waves: a syncopated bass careening off a jazz drummer with a Senagalese melody line sung by Cheikh and R&B horns, funk piano, and heavy Senegalese percussion. It’s the kind of mash up that takes talent to put together without making a mess. This is some of the most intricately layered and yet totally stinky funk you ever want to experience. It’s astounding.

Here is where the story turns mysterious. Cheikh Lô has a new album, Senegal Bresil but I couldn’t find any information in English on it, nor is it available from the usual suspects States-side, i.e. no Amazon, no iTunes. You have to do some deep trolling to find it. I believe I got it off a Russian site.

Anyway, I am totally enthralled by what my man is doing. It’s really a remake of Lamp Fall. As near as my extremely poor translations can make out, what had happened was: Cheikh Lô decided to do an album specifically for an African audience but instead of composing all new material, Lô chose to re-record selections from Lamp Fall with Brazilian musicians. So Cheikh went to Brazil and hooked up with percussionist Samba Ndoh and recorded in Salvador (the capital of Bahia, Brazil).

I know that some critics find Lô’s music “too modern” or even “gimmicky” because of all the varied influences that shine through. I think it reflects the African aesthetic of both/and rather than the classical Euro-dynamic of either/or. Of course that is a simplification but it may help one to appreciate that Lô is not trying to be different, nor is he reaching for an international (i.e. “Euro/American” audience); indeed, Cheikh Lô already is international, it’s just that the different nations he chooses to address are those with strong African Diaspora and African heritage elements.

The new album is on the World Circuit label and is described as “Senegal-Bresil: Reggae Rhythms And Mbalax For De Salvador De Bahia.” This is probably the most interesting “crossover” album in decades—Lô is crossing from black to black, whereas “crossover” traditionally has referred to non-white moving toward Euro/American audiences / aesthetics / tastes.

“Sante Yalla” opens with samba drums before quickly slipping into a Cuban clave. “Senegal-Bresil” is a self-explanatory mix of mbalax and samba. I’m not quite sure how to describe “Bamba Mo Woor” except to say that it resides way above ground level, floating on a funky cloud, or is it a orbiting on a satellite?

While I don’t think everything on Senegal Bresil works as smoothly as Lamp Fall, I do think it is one of the most daring developments of the past twenty years or so in attempting to move contemporary African music forward.

What is most significant is that I don’t have translations of the music. I’m only vibing on the sound. I can’t catch the lyrical sense, the political points. Language barriers notwithstanding, I totally enjoy the sounds I do understand: the rhythms, the melodies, the harmonies.

Political Pan-Africanist can only dream of uniting across national boundaries, through the music Cheikh Lô is making Pan-Africanism a reality. Significantly, regardless of how many influences Lô stirs into the pot, the Senegalese identity remains intact.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

A lot of listening

After reading this write-up, I'm embarassed to admit this, but before this week, I'd only ever heard one song by Cheikh Lô. Even worse, I had no idea he was a major artist. So far, I've only listened to these tracks one time through each, but I'm most impressed by the Senegal Bresil material. It's like a strange and intoxicating mashup of reggae, MPB and traditional Senegalese sounds. The other thing is, I knew a little something about Africando, and already have a few of their tracks, but I didn't know they had any connection to Senegal. I'm digging the Pape Fall too (another cat I've never before even heard of). Man, oh, man do I have a lot of listening to do.

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, April 6th, 2008 at 11:48 pm and is filed under Contemporary. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

4 Responses to “CHEIKH LO / “Bambay Gueej””

April 7th, 2008 at 6:53 pm

As one of your faithful listeners from way back in Dakar Senegal, last week’s set provided literal hours of musical journeying for my family of literal African Americans. I thought to myself, it can’t get any better than this – Stevie and Senegal? My two passions, my two halves brought together in rhythmic celebration?

And then, ya’ll topped yourselves by offering week 2! God Bless ya’ll brothers, you are doing mighty, mighty work. You are one of the few places in cyberspaces where the Black world always meets in celebration! And the story you tell of salsa and mbalax is my own family’s story. Salsa being the music of my mother’s generation of post independence cross pollination flavor. Somewhere in the seventies (about the time my Senegalese mother had settled in Harlem NYC with my Caribbean father), the salsa rage was still the sets that connected her with the Afro Puerto Rican/Cuban/Dominican communities we were living amongst. I remember as a young girl feeling their absolute shock and delight at the mighty distance music was traveling. Likewise, I remember how much of Stevie’s always on time ballad stirred in my mother a beautiful burgeoning sense of connection to this new place she was calling home…

By the time my (now divorced) mother returned with us to Dakar in the 80’s, mbalax had taken over, and Youssou Ndour and his Super Etoile were all the rage. Salsa was seen as the music of the post colonial elite – the soundtrack of all things imported if you will. The music of access and nepotism, whereas the fees to get into the clubs where mbalax were playing, well… we know who was there and wasn’t. The riddims were fast, and the dances were dirty and required the skills of a generation of young folks reaching past salsa to something else. Mbalax brought with it a pride in what it meant to be Senegalese.

Katharina Kane writes about this I believe on her liner notes to Orchestra Baobab’s newest album.

Without making this too long, please know that Senegal, despite so much transition is integrating both aspects of itself, Pape Faye has weekly sets where the dance floor is always packed, and well any dj worth his weight, at either house party or club knows that the expectation is to rock multi flavored sets of both salsa and mbalax at party pitch before turning to – can you guess… hip hop! And not the local kind, either.

Djere dieuff (righteous thanks), brothers, for keeping not only my fam but the global Black fam connected. Your space is one of the few where the Black world meets in celebration. We can hardly wait to see you on this side of the Atlantic soon… Perhaps a New Year’s dj Kalaamu/Mtume party on Goree Island?

April 11th, 2008 at 4:36 pm

a lovely quote to open your reflection on Lo’s music. when I first saw him perform live, each song unfolded like a fresh chapter in a very cool book on the evolution of african music. the funk and grooves were undeniable, but as you danced extra beats and rhythmic hooks emerged which continually challenged and delighted. the traditional influences were there, but it was so obviously something new being forged. somebody spoke recently about playing, dancing or grooving to music as being one of those few times where your head, heart and body are fully engaged in something beautiful. that seems particularly true for this man’s music

May 9th, 2008 at 10:32 am

I missed this earlier. Just a couple of quick observations. The remark that Cheikh Lo’s second K7 was unreleased because he didn’t think it was good enough is something you picked up off a sleeve note – I think from the CD release of “Ne la thiass”. Not true. Like “Doxandeme” his first, “Dieufdieul” was issued on the Audio Video label. I have K7 and CD copies of both – but “Dieufdieul” is very rare in K7 form. Perhaps it was issued and withdrawn by Robert Lahoud, the French guitarist who appears to have owned the label.

I saw Cheikh Lo live in St Louis, Senegal in 1997. His performance was completely different to how he comes over on “Ne la thiass” and subsequent albums, which are somewhat meditative and very subtle. He was absolute dynamite! Little Richard could NOT have stood on the same stage! I saw him a couple of years later in London and he was as you hear him in his Jololi recordings.

MG

May 9th, 2008 at 10:39 am

PS Cheikh Lo used to play drums in Ouza’s band. Along with Grant Green, Ouza is my all time favourite musician. Ouza named his son Cheikh Lo. He plays keyboards in Ouza’s band now.

MG

Leave a Reply

| top |