FREDDIE HUBBARD / “Red Clay”

Rap and jazz are both more and less connected than you’d think. Kalamu argued the former in a post on Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman.” “Rap took the popular song form,” he wrote, “obliterated the harmony part, and emphasized preaching over a beat. And that was a revolutionary development, a development foreshadowed by what had already happened in the jazz world.” While I thought then, and still think, that Kalamu’s explanation of the connection was overly literal, the fact remains that there are basic similarities—i.e., ‘riffing over rhythm,’ ‘preaching over a beat,’ etc.—that the two genres share. On the other hand, the connection between rap and jazz is too often overstated. As I tried to explain in a post a couple f week’s back, the vast majority of rap music has neither of the essential elements of jazz—those essential elements being melodic improvisation and rhythmic swing—and therefore, it doesn’t make much sense to talk about the ‘jazz elements’ of a rap record when what we’re really talking about are simply jazz samples.

So why do rap producers sample jazz records? I don’t think it’s necessary to overly complicate matters. I’d say that rap DJs or producers sample jazz records for the same reason they sample any other record: because they hear in that particular record a groove that they like. Or they hear a unique sonic texture created by the interplay of the musicians who recorded the song. Or they hear something else that they either can’t or don’t want to duplicate on their own. When a loop is sampled from a record, the sonic texture—the unquantifiable essential ‘somethingness’ of a record that we’ll just call ‘feel’—goes with it. This accounts, at least in part, for the reason I love listening to jazz tunes that have riffs I recognize from samples. I’m hearing and responding to not just the original (jazz) song but also, by association, I’m hearing and responding to the hip-hop song that’s playing in my (subconscious) mind.

One of my favorite jazz tunes in this vein is trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s “Red Clay” (from the 1970 CTI album also named Red Clay). The groove—courtesy of Lenny White on drums and Ron Carter (“yes, my man Ron Carter”) on the bass—is damn near perfect. Hubbard’s opening trumpet solo is excellent as well—searching, piercing, fluid. Herbie Hancock’s lengthy electric piano showed that he was still coasting right there in the sweet spot—a place he’d been comfortably occupying for several years as a co-member (along with session-mate Ron Carter) of Miles’ famed quintet. The legendary saxman Joe Henderson rounds out the all-star band, making this quintet one of the heaviest in jazz pedigree to ever grace a bandstand.

Other sample-delic jazz tracks I love run the gamut from the light jazz-funk of Lou Donaldson’s “Pot Belly” (from Pretty Things, Blue Note – 1970) to the sensual groove stew of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers’ “A Chant For Bu” (from Buhaina, 1973). And of course, there’s the tune Nadir mentioned in the comments section just two weeks ago—and which I’ve since managed to track down—Cannonball Adderley’s out-of-print “Walk Tall.” I should also mention a couple of tunes that we’ve previously discussed at BoL, those being Lou Donaldson’s “Ode To Billie Joe” and Ronnie Foster’s “Mystic Brew.” And just in case you haven’t noticed the theme yet, all of these tunes weren’t just sampled by rappers in general, they were sampled by A Tribe Called Quest, specifically. Check it out, y’all.

—Mtume ya Salaam

Sound is identity

Bass Heavy smiled at me and explained that he thinks sampling a beat (meaning, sampling an entire rhythm loop from one source) is cheating. He and I were producing the music for Baby Love, a 75-minute movie I directed. I had specific music ideas I wanted to realize: an Afro-Cuban vibe here, a Brazilian samba beat there, a Miles fusion sound over here, and so forth. I understood what Bass Heavy was saying, so we started in to build our drum sounds. Once we got the sound we wanted, we laid down the beats.

You might think there can’t be that much difference between, say, one rim shot and another or between one snare pop and another, but there is, and we were looking for the right combination. Bass smiled again and picked up his secret weapons: a handful of CDs with nothing but drum sounds on them. I forget which track it was, but I distinctly remember selecting a Blue Note snare drum sound. And you know what? Bass Heavy had no way of telling whose sound it was because all he did was record drum hit after drum hit after drum hit. Not a whole lick or pattern, just the one sound of the stick hitting the drum. At that moment I fully understood that sound is identity.

Even when I could not identify who the drummer was, I could easily hear the difference between the hits, and when he switched from Blue Note to another label, there was an even more dramatic difference in the sound. It was not just the drummer, it was also the way the drummer was recorded. Needless to say it took us hours to build a drum pattern. The bass drum hit came from one source, the snare from another, a rim shot from another, the ride cymbal from another, a cymbal crash for another. (In fact, with the cymbal crash we even reversed it to get a certain sound—that was a trick I got from Stevie Wonder.)

There’s a lot more to sampling a beat than meets the average ear. I won’t even bother to revisit the jazz/rap discussion. We’ll get to that at another time. Right now I just want to concentrate your attention on the drums—the sound of the drums and the way the drummers play.

The late Sixties/early Seventies were a transitional period in jazz. Swinging was quickly becoming a thing of the past. Everybody was grooving, which inevitably meant playing with a backbeat. (Usually, a heavy emphasis on the fourth beat). This became the major difference between playing jazz and playing funk/R&B.

Paradoxically, while it may seem obvious that swinging calls for a different approach than laying on the backbeat, it’s also true that jazz drummers are generally not adept at playing funk. Jazz drumming and funk drumming are actually different disciplines. Listen to the four cuts Mtume has selected and you will hear four different approaches.

One of my favorite jazz tunes in this vein is trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s “Red Clay” (from the 1970 CTI album also named Red Clay). The groove—courtesy of Lenny White on drums and Ron Carter (“yes, my man Ron Carter”) on the bass—is damn near perfect. Hubbard’s opening trumpet solo is excellent as well—searching, piercing, fluid. Herbie Hancock’s lengthy electric piano showed that he was still coasting right there in the sweet spot—a place he’d been comfortably occupying for several years as a co-member (along with session-mate Ron Carter) of Miles’ famed quintet. The legendary saxman Joe Henderson rounds out the all-star band, making this quintet one of the heaviest in jazz pedigree to ever grace a bandstand.

Other sample-delic jazz tracks I love run the gamut from the light jazz-funk of Lou Donaldson’s “Pot Belly” (from Pretty Things, Blue Note – 1970) to the sensual groove stew of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers’ “A Chant For Bu” (from Buhaina, 1973). And of course, there’s the tune Nadir mentioned in the comments section just two weeks ago—and which I’ve since managed to track down—Cannonball Adderley’s out-of-print “Walk Tall.” I should also mention a couple of tunes that we’ve previously discussed at BoL, those being Lou Donaldson’s “Ode To Billie Joe” and Ronnie Foster’s “Mystic Brew.” And just in case you haven’t noticed the theme yet, all of these tunes weren’t just sampled by rappers in general, they were sampled by A Tribe Called Quest, specifically. Check it out, y’all.

—Mtume ya Salaam

Sound is identity

Bass Heavy smiled at me and explained that he thinks sampling a beat (meaning, sampling an entire rhythm loop from one source) is cheating. He and I were producing the music for Baby Love, a 75-minute movie I directed. I had specific music ideas I wanted to realize: an Afro-Cuban vibe here, a Brazilian samba beat there, a Miles fusion sound over here, and so forth. I understood what Bass Heavy was saying, so we started in to build our drum sounds. Once we got the sound we wanted, we laid down the beats.

You might think there can’t be that much difference between, say, one rim shot and another or between one snare pop and another, but there is, and we were looking for the right combination. Bass smiled again and picked up his secret weapons: a handful of CDs with nothing but drum sounds on them. I forget which track it was, but I distinctly remember selecting a Blue Note snare drum sound. And you know what? Bass Heavy had no way of telling whose sound it was because all he did was record drum hit after drum hit after drum hit. Not a whole lick or pattern, just the one sound of the stick hitting the drum. At that moment I fully understood that sound is identity.

Even when I could not identify who the drummer was, I could easily hear the difference between the hits, and when he switched from Blue Note to another label, there was an even more dramatic difference in the sound. It was not just the drummer, it was also the way the drummer was recorded. Needless to say it took us hours to build a drum pattern. The bass drum hit came from one source, the snare from another, a rim shot from another, the ride cymbal from another, a cymbal crash for another. (In fact, with the cymbal crash we even reversed it to get a certain sound—that was a trick I got from Stevie Wonder.)

There’s a lot more to sampling a beat than meets the average ear. I won’t even bother to revisit the jazz/rap discussion. We’ll get to that at another time. Right now I just want to concentrate your attention on the drums—the sound of the drums and the way the drummers play.

The late Sixties/early Seventies were a transitional period in jazz. Swinging was quickly becoming a thing of the past. Everybody was grooving, which inevitably meant playing with a backbeat. (Usually, a heavy emphasis on the fourth beat). This became the major difference between playing jazz and playing funk/R&B.

Paradoxically, while it may seem obvious that swinging calls for a different approach than laying on the backbeat, it’s also true that jazz drummers are generally not adept at playing funk. Jazz drumming and funk drumming are actually different disciplines. Listen to the four cuts Mtume has selected and you will hear four different approaches.

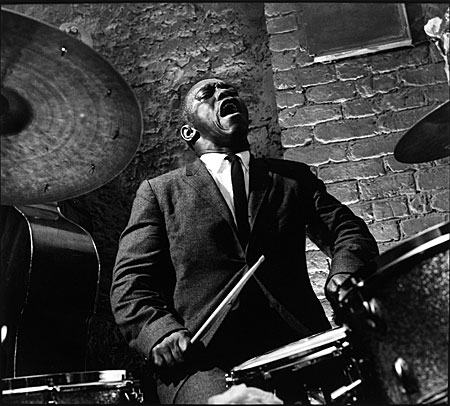

Art Blakey, the dean of jazz drumming and generally acknowledged as one of the swingingest drummers of post-war jazz, doesn’t even offer a hint of backbeating. Blakey enters with his trademark press/roll crescendo and proceeds to drop a polyrhythmic dissertation in swing. Listen to his cymbal work. He is not keeping a steady one, two, three, four, instead he is accenting the beat, consistently playing in between the beats but maintaining momentum by using mini-breaks. He didn’t usually record with a conga player (aside from his Fifties-era experimentation with Afro-Cuban and African rhythms) so this cut is unusal in that way. This is a jazz track all the way. I suspect folk like the theme statement more than the track it self.

Art Blakey, the dean of jazz drumming and generally acknowledged as one of the swingingest drummers of post-war jazz, doesn’t even offer a hint of backbeating. Blakey enters with his trademark press/roll crescendo and proceeds to drop a polyrhythmic dissertation in swing. Listen to his cymbal work. He is not keeping a steady one, two, three, four, instead he is accenting the beat, consistently playing in between the beats but maintaining momentum by using mini-breaks. He didn’t usually record with a conga player (aside from his Fifties-era experimentation with Afro-Cuban and African rhythms) so this cut is unusal in that way. This is a jazz track all the way. I suspect folk like the theme statement more than the track it self.

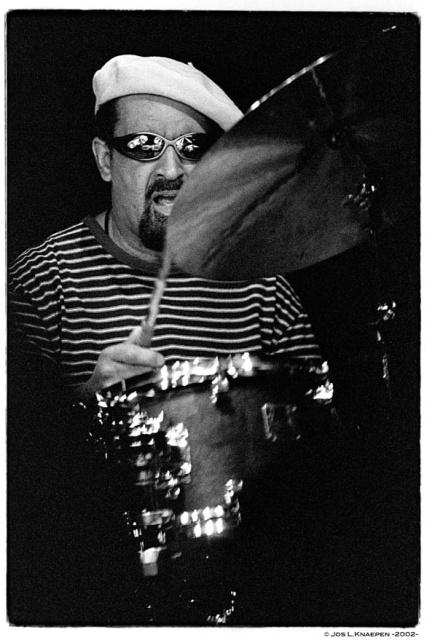

The band on the Lou Donaldson session is Blue Mitchell on trumpet, Dr. Lonnie Smith on organ, Melvin Sparks on guitar, Jimmy Lewis on bass and Idris Muhammad on drums. Even before I checked, I figured that was Idris; the man has his own groove. He plays the cymbals in a steady old-school swing sort of way (very different from how Blakey does it). The popping snare is mainly accents. What Idris does that is distinctive is put his foot into the backbeat. Listen to him dropping those double-bumps followed by a soft snare pop, thereby giving the backbeat a definite emphasis, yet sounding different from most backbeats. As sweet as Idris’ drumming is, the track doesn’t make it for me because the solos are so uninspired.

The band on the Lou Donaldson session is Blue Mitchell on trumpet, Dr. Lonnie Smith on organ, Melvin Sparks on guitar, Jimmy Lewis on bass and Idris Muhammad on drums. Even before I checked, I figured that was Idris; the man has his own groove. He plays the cymbals in a steady old-school swing sort of way (very different from how Blakey does it). The popping snare is mainly accents. What Idris does that is distinctive is put his foot into the backbeat. Listen to him dropping those double-bumps followed by a soft snare pop, thereby giving the backbeat a definite emphasis, yet sounding different from most backbeats. As sweet as Idris’ drumming is, the track doesn’t make it for me because the solos are so uninspired.

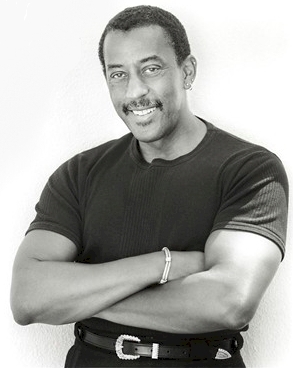

Now Freddie Hubbard’s “Red Clay” is the most exciting track jazz-wise because the solos are bad and the rhythm section is killing, mainly because of bassist Ron Carter who makes it easy super-easy for drummer Lenny White. In fact, many people recognize “Red Clay” by the bass line alone. When you have a bass player holding down the bottom like Ron Carter does, as a drummer you don’t have to do much. Plus, the soloist are blowing their tails off. If you concentrate on Carter’s bass lines, you will find yourself mesmerized.

Now Freddie Hubbard’s “Red Clay” is the most exciting track jazz-wise because the solos are bad and the rhythm section is killing, mainly because of bassist Ron Carter who makes it easy super-easy for drummer Lenny White. In fact, many people recognize “Red Clay” by the bass line alone. When you have a bass player holding down the bottom like Ron Carter does, as a drummer you don’t have to do much. Plus, the soloist are blowing their tails off. If you concentrate on Carter’s bass lines, you will find yourself mesmerized.

Now for the Cannonball set, I’ll simply say check out how locked into the pocket Roy McCurdy is, and yet at the same time Roy does not play the same lick over and over again. He snaps a hard backbeat on the four, yet roams free on the one, two and three. It is an exciting amalgamation of the metronomic backbeat of funk and the freedom of jazz swing. By the way, that’s Nat Adderley on cornet, Joe Zawinul of keys, Victor Gaskin on bass, and Cannonball on alto.

In fact, I believe I ought to call Bass Heavy and tell him to pick up on Roy McCurdy’s snare pop. It’s fat, phat and all that. Notice too that Roy's playing is dominated by the snare sound whereas Blakey was all over the kit, Idris was emphasizing the bass drum and Lenny White was riding his cymbals. It’s amazing what you can hear when you listen to masters.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

A master jazz writer

Actually, what's amazing is what you can hear when you listen to masters along with a master. A master jazz writer, that is.

We were late getting this week's BoL together. Sometimes, it's a comedy of errors. Kalamu had a last-minute meeting. I somehow lost or deleted or wrote-over my original "Red Clay" write-up. It was a mess. So by the time I hit the sack Saturday night, Kalamu was still out and about—he hadn't yet posted this response. I thought, "Oh well. In the morning, I'll check out Kalamu's response and give the jukebox a spin to make sure everything is straight." (Which is what I usually do Saturday night.)

So I woke up this morning, fired up the ol' eMac and pressed 'play' on the jukebox. The Good Reverend Jesse Jackson yelled "Walk tall!" and off he went. Then I started reading Kalamu's post. At first, I was just kind of reading along, thinking, "Right, right," or, "OK, I can dig that," or, "Damn, that's what I should've said," or whatever. But then I got to the part where Kalamu started breaking down into intricate details, down to the sub-atomic level, each drummer's varying technique. Before I knew it, I couldn't even hear the music anymore. I was lost in the words, following along with what Kalamu was saying, learning more than I ever hoped to know about music that I selected!

Kalamu made mention of this a few weeks ago, but one of the strengths of our little thing is that our specialties lie in different areas of the music. I might not listen to a whole lot of hip-hop anymore, but anyone who reads BoL on a weekly basis knows that hip-hop is where my heart is. It's me. R&B and Soul are like brothers to me—I love 'em, I know 'em, I feel what they do. Other styles are like good friends—I can kick it with a whole variety of electronic, or rock, or alternative styles and while I don't feel like I do when I'm with family, I'm still in my element. It's cool. I got my cousins that I love to death: reggae, samba, salsa, a whole handful of African styles, I could go on and on. I don't know them as well as I know my other folks, but I always dig what they have to say. Then there are the older folks—Paw Blues, Maw Gospel and yes, Jazz. Those are my grandparents. I got a couple of them from back home (Blues and Gospel). They're good, good people. Wise, steady, true. Sometimes they disagree with each other, arguing and fussing in front of the grandkids, but the truth is, they're as real as real gets. Without them, I wouldn't, couldn't be here today. But then there's Jazz. Man. That's my Maw and Paw from, well, sometimes I think they're from everywhere. They may have been born back home—not to far from where Paw Blues and Maw Gospel still stay—but by now, they've traveled the world. They're complicated, moody, worldly and supremely intellectual. I'm never exactly sure where they're coming from. Sometimes, they come at me from such unforeseen, unlikely angles that I don't know what to make of what they're putting down. Then, just when I've gotten used to their strangeness, they come at me straight. I'm sitting there looking for the angle and there isn't one. (Unless you're hip to the fact that a straight line can be an angle too. But that's a jazz thing. I won't try to get to deep into that.)

Anyway, the point I'm trying to make is, as much as I dig jazz as a sound, as a style, as a feeling, as a groove, when I listen to it or write about it, the most I can do is scratch the surface. I can point the way to some hip sounds, but I damn sure can't get down deep beneath the surface, excavating, extricating and illuminating the minute (but oh so important) details the way Kalamu can. Hell, the only reason I even know these tunes exist, is because one of my favorite hip-hop crews sampled them! Meanwhile, Kalamu's breaking down the vagueries of each drummer's methodology. I guess that about says it all.

—Mtume ya Salaam

Now for the Cannonball set, I’ll simply say check out how locked into the pocket Roy McCurdy is, and yet at the same time Roy does not play the same lick over and over again. He snaps a hard backbeat on the four, yet roams free on the one, two and three. It is an exciting amalgamation of the metronomic backbeat of funk and the freedom of jazz swing. By the way, that’s Nat Adderley on cornet, Joe Zawinul of keys, Victor Gaskin on bass, and Cannonball on alto.

In fact, I believe I ought to call Bass Heavy and tell him to pick up on Roy McCurdy’s snare pop. It’s fat, phat and all that. Notice too that Roy's playing is dominated by the snare sound whereas Blakey was all over the kit, Idris was emphasizing the bass drum and Lenny White was riding his cymbals. It’s amazing what you can hear when you listen to masters.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

A master jazz writer

Actually, what's amazing is what you can hear when you listen to masters along with a master. A master jazz writer, that is.

We were late getting this week's BoL together. Sometimes, it's a comedy of errors. Kalamu had a last-minute meeting. I somehow lost or deleted or wrote-over my original "Red Clay" write-up. It was a mess. So by the time I hit the sack Saturday night, Kalamu was still out and about—he hadn't yet posted this response. I thought, "Oh well. In the morning, I'll check out Kalamu's response and give the jukebox a spin to make sure everything is straight." (Which is what I usually do Saturday night.)

So I woke up this morning, fired up the ol' eMac and pressed 'play' on the jukebox. The Good Reverend Jesse Jackson yelled "Walk tall!" and off he went. Then I started reading Kalamu's post. At first, I was just kind of reading along, thinking, "Right, right," or, "OK, I can dig that," or, "Damn, that's what I should've said," or whatever. But then I got to the part where Kalamu started breaking down into intricate details, down to the sub-atomic level, each drummer's varying technique. Before I knew it, I couldn't even hear the music anymore. I was lost in the words, following along with what Kalamu was saying, learning more than I ever hoped to know about music that I selected!

Kalamu made mention of this a few weeks ago, but one of the strengths of our little thing is that our specialties lie in different areas of the music. I might not listen to a whole lot of hip-hop anymore, but anyone who reads BoL on a weekly basis knows that hip-hop is where my heart is. It's me. R&B and Soul are like brothers to me—I love 'em, I know 'em, I feel what they do. Other styles are like good friends—I can kick it with a whole variety of electronic, or rock, or alternative styles and while I don't feel like I do when I'm with family, I'm still in my element. It's cool. I got my cousins that I love to death: reggae, samba, salsa, a whole handful of African styles, I could go on and on. I don't know them as well as I know my other folks, but I always dig what they have to say. Then there are the older folks—Paw Blues, Maw Gospel and yes, Jazz. Those are my grandparents. I got a couple of them from back home (Blues and Gospel). They're good, good people. Wise, steady, true. Sometimes they disagree with each other, arguing and fussing in front of the grandkids, but the truth is, they're as real as real gets. Without them, I wouldn't, couldn't be here today. But then there's Jazz. Man. That's my Maw and Paw from, well, sometimes I think they're from everywhere. They may have been born back home—not to far from where Paw Blues and Maw Gospel still stay—but by now, they've traveled the world. They're complicated, moody, worldly and supremely intellectual. I'm never exactly sure where they're coming from. Sometimes, they come at me from such unforeseen, unlikely angles that I don't know what to make of what they're putting down. Then, just when I've gotten used to their strangeness, they come at me straight. I'm sitting there looking for the angle and there isn't one. (Unless you're hip to the fact that a straight line can be an angle too. But that's a jazz thing. I won't try to get to deep into that.)

Anyway, the point I'm trying to make is, as much as I dig jazz as a sound, as a style, as a feeling, as a groove, when I listen to it or write about it, the most I can do is scratch the surface. I can point the way to some hip sounds, but I damn sure can't get down deep beneath the surface, excavating, extricating and illuminating the minute (but oh so important) details the way Kalamu can. Hell, the only reason I even know these tunes exist, is because one of my favorite hip-hop crews sampled them! Meanwhile, Kalamu's breaking down the vagueries of each drummer's methodology. I guess that about says it all.

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, July 16th, 2006 at 2:34 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

4 Responses to “FREDDIE HUBBARD / “Red Clay””

July 17th, 2006 at 1:41 pm

NIIIICE set for this segment. I noticed the Tribe Called Quest theme from Red Clay. The only question is that I guess I never read the liner notes for several of Tribe’s songs but I thought they sampled/interpolated The Last Poets’ “Tribute to Obabi” instead of ‘A Chant for Bu’

BTW, when Kalamu said, “Listen to his cymbal work. He is not keeping a steady one, two, three, four, instead he is accenting the beat, consistently playing in between the beats but maintaining momentum by using mini-breaks.” I would agree. However, I thought most GOOD percussionists do that anyway. Maybe I was misinformed.

BTW, Pot Belly does not work or sounds unusually garbled.

July 18th, 2006 at 6:25 am

I can hear Grand Puba somewhere when I hear Walk Tall. What song was that???!!!

one love,

Ekere

Mtume says:

That was Brand Nubian. "Concerto In X Minor."

July 18th, 2006 at 7:23 pm

Nice work the last couple of weeks w/ The Tribe, then segue to jazz artists they’re connected to via sample. I’m a die-hard Blakey fan so was startled/excited to hear that the sample opening Low End Theory was Buhaina(‘s). Am thankful in the vein that Mtume alludes to for hip-hop artists leading me to so much fine jazz.

Speaking of, any way to tie in a post of “Up Jumped Spring” ? Maybe it’s me getting old and sentimental, but that song gets more beautiful every time I hear it.

July 19th, 2006 at 9:24 pm

nice choice on the freddie hubbard cut. have either of you heard the ‘red clay’ cover by dwele and roy hargrove, performed live on gilles peterson’s show? it was comped on gp’s ‘bbc sessions’ double disc that came out last year.

Mtume says:

I haven’t heard that, but I’d like to. Somebody hit me up. mtume_s@yahoo.com

Leave a Reply

| top |