ERIC B. & RAKIM / “In The Ghetto”

Last week, we posted three funk classics: Bill Withers’ “Kissing My Love,” Labi Siffre’s “I Got The” and The Meters’ “Just Kissed My Baby.” This week we’re going with three hip-hop classics, Eric B. & Rakim’s “In The Ghetto,” Jay-Z’s “Streets Is Watching” and Public Enemy’s “Timebomb.” Extra points if you’ve already figured it out, but we selected these three records for a specific reason. More on that later.

“In The Ghetto” is a track from 1990’s Let The Rhythm Hit ‘Em, the third of Eric B. & Rakim’s four albums as a duo and arguably the weakest. There’s nothing weak about the track itself, however. All of Rakim’s trademark skills are on display. There’s his penchant for abstract or philosophical concepts: “I learned to relax in my room and escape from New York / Then return through the womb of the world as a thought.” Internal rhyme schemes and frequent alliteration: “Any stage I'm seen on, or mic I fiend on / I stand alone and need nothing to lean on.” Then there’s my favorite aspect of Rakim’s style, the extended metaphors and visual imagery. Here, he rhymes about the many places and methods in which he’s left his mark, from his stomping grounds to foreign lands, from the stages to the streets and even with the ladies:

“In The Ghetto” is a track from 1990’s Let The Rhythm Hit ‘Em, the third of Eric B. & Rakim’s four albums as a duo and arguably the weakest. There’s nothing weak about the track itself, however. All of Rakim’s trademark skills are on display. There’s his penchant for abstract or philosophical concepts: “I learned to relax in my room and escape from New York / Then return through the womb of the world as a thought.” Internal rhyme schemes and frequent alliteration: “Any stage I'm seen on, or mic I fiend on / I stand alone and need nothing to lean on.” Then there’s my favorite aspect of Rakim’s style, the extended metaphors and visual imagery. Here, he rhymes about the many places and methods in which he’s left his mark, from his stomping grounds to foreign lands, from the stages to the streets and even with the ladies:

People in my neighborhood, they know I'm good From London to Hollywood, wherever I stood Footprints remain on stage ever since Sidewalks and streets, I leave fossils and dents When I had sex, I left my name on necks My trademark was left throughout the projects

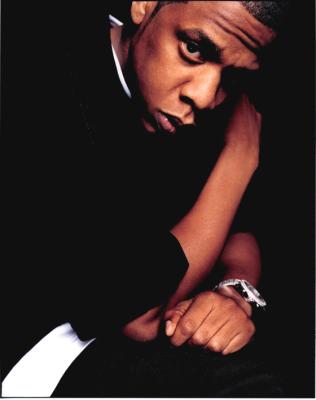

“The Streets Is Watching,” a track from Jay-Z’s second release, 1997’s In My Lifetime, Vol. 1, is a song-length examination, explanation and justification of Jay’s all-consuming desire for financial gain. Although the song details Jay’s reasons for switching occupations from drug dealing to MCing, his thought process indicates neither remorse nor morality. In fact, his primary reasoning seems to be that he’s so good at what he does (whether rapping or dealing) that notoriety follows him like bad credit. But while fame equals money in the entertainment business, fame equals problems in his former profession. So right from the start, Jay gets to the point: “Look, if I shoot you, I’m brainless / But if you shoot me, you’re famous / What’s a nigga to do?” Hence, early retirement.

But the only thing that’s really changed, Jay says, is methodology. His goal—to secure to capital—remains the same:

“The Streets Is Watching,” a track from Jay-Z’s second release, 1997’s In My Lifetime, Vol. 1, is a song-length examination, explanation and justification of Jay’s all-consuming desire for financial gain. Although the song details Jay’s reasons for switching occupations from drug dealing to MCing, his thought process indicates neither remorse nor morality. In fact, his primary reasoning seems to be that he’s so good at what he does (whether rapping or dealing) that notoriety follows him like bad credit. But while fame equals money in the entertainment business, fame equals problems in his former profession. So right from the start, Jay gets to the point: “Look, if I shoot you, I’m brainless / But if you shoot me, you’re famous / What’s a nigga to do?” Hence, early retirement.

But the only thing that’s really changed, Jay says, is methodology. His goal—to secure to capital—remains the same:

My street mentality? Flip bricks forever You know me and money / We’re like armed co-defendants, nigga we stick together Shit, whatever for this cheddar / Ran my game into the ground Hustle harder to see if indictment time came around Now you can look up and down the streets and I can't be found Put in twenty-four hour shifts but that ain't me now….Not on the streets, at least. Because as Jay-Z has proven over the years, he has a gift for being where the money is, for staying just enough ahead of the curve to always have options. A decade later, he’s still writing songs about retirement from ‘the game.’ Only now, he’s trying to make the move from the studio to the board room. And you’d best believe it’s still all about money.

“Timebomb,” a track from Public Enemy’s 1987 debut release, Yo! Bum Rush The Show, is the oldest of this week’s classics and it shows. By today’s standards, Chuck’s direct style and basic rhyme schemes sound antiquated. Still, of the three, this is my favorite track—it may be a twenty-year old record, but it still hits me as hard as it ever did. Chuck’s delivery is so animated that it’s hard to listen to this record without feeling some of his excitement. “Timebomb” (and the entire Bum Rush The Show album) predates Public Enemy’s intense focus on the political. So although Chuck makes a few political references (“I’m a South African government wrecker”), this is essentially a freestyle. Chuck simply grabs the mic, rips it up and stops when he’s done. There’s not even a chorus.

“Timebomb,” a track from Public Enemy’s 1987 debut release, Yo! Bum Rush The Show, is the oldest of this week’s classics and it shows. By today’s standards, Chuck’s direct style and basic rhyme schemes sound antiquated. Still, of the three, this is my favorite track—it may be a twenty-year old record, but it still hits me as hard as it ever did. Chuck’s delivery is so animated that it’s hard to listen to this record without feeling some of his excitement. “Timebomb” (and the entire Bum Rush The Show album) predates Public Enemy’s intense focus on the political. So although Chuck makes a few political references (“I’m a South African government wrecker”), this is essentially a freestyle. Chuck simply grabs the mic, rips it up and stops when he’s done. There’s not even a chorus.

- Eric B. & Rakim - “In The Ghetto” from Let The Rhythm Hit 'Em

(MCA, 1990)

- Jay-Z – “Streets Is Watching” from In My Lifetime, Vol. 1

(Roc-A-Fella, 1997)

- Public Enemy – “Timebomb” from Yo! Bum Rush The Show

(Def Jam, 1987)

—Mtume ya Salaam

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, March 12th, 2006 at 12:55 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

6 Responses to “ERIC B. & RAKIM / “In The Ghetto””

March 12th, 2006 at 6:01 am

I’m not trying to be sarcastic kalamu, but what is your definition of a song? You make a valid point with the selections on this weeks BOL, but there are classics that occupy my cd/cassette racks/and consciousness that makes me question your “song/rap” theory.

Public Enemy: It takes a nation of millions to hold us back

De La Soul: Buhloone Mind State

Outkast: Atliens

the raps on these albums sound like songs to me.

“Why we listen to it at all”

My generation was more interested in “digging” for those samples that the Diddys of today wouldn’t use. We were exposed and in most cases reunited with songs that our parents dug. Hip hop is the reason why i have a lot of gems from eras that preceeded my existence. Sometimes a nice sample was a sweet scent that lead us “curious kids” to good music. Some of those loops we mistakened for “egyptian musk” also guided us into pastures of shitty songs to.

Kalamu,

how can anyone judge music they haven’t listened too?

Your peers are “wick, wick, WACK!

March 12th, 2006 at 5:21 pm

"As far as I am concerned any art which is mainly about the bottom line will never rise to the heights of great art because such art lacks heart." – kalamu Now, as a hip hop head, this is my biggest concern with the culture. The majority of the artists behind the mic are speaking of the music as a "hustle", the alternative to the crack game. MInd you, this is only a component of the culture. However, this component has grown to the point that it’s now the dominant and most heard voice in the culture. In hip hop there are poets and rappers. Poets internalize the world. Rappers externalize the world. Poets are felt, rappers are heard. Ultimately, the rapper says what people want to hear, usually party and bullshit. The poet however says what NEEDs to be said, and over time, people revisit those records long after the party and bullshit is over. But whether it’s the work of a poet, or rapper, you can’t dismiss hip hop music and say they aren’t songs. That’s crazy. The Last Poets didn’t make songs? Sure they did. Sample or no sample. Strip the music away and listen. A great song is a great song even over nothing but the sounds of snapping fingers. "Their" prejudice and lack of understanding made "them" dismiss jazz as music, initially. How stupid do we look, when we do the same thing to "our" own music? One luv.

kalamu says

hardCore and Nadir are asking a similar question. i think most people use the term "song" in two ways without distinguishing one from the other. the first way as a catch-all phrase referring to any relatively short musical composition or performance, the second way as a reference to a musical composition in which a vocalist who is singing is the lead. from the first perspective a rap is clearly a song. from the second perspective a rap is music but it is not a song.

when i raised the question i was intentionally dealing with the hardcore rap perspective that a "good rap song" does not need a singer and that many of these raps that do include singers are, at best, pandering to a general audience in order to be popular. yall know exactly what i mean.

i believe the western song form (what key, stevie, what key?) is one convenient sub-genre of music. we don’t have to try to fit everything into that subdivision, especially with regards to rap. if folk want to call rap a song, that’s ok with me, i’m just asking why? why do we need to reference everything we do to pre-existing western forms and have our thing fit into a western norm, an approach that was designed to exclude us. of course jazz is music, but it is not classical music (unless you want to argue that jazz is "our black classical music," which argument inherently is challenging the western notion of classical music. once again going back to the two uses of the term, classical = the best of a specific category, or classical = a specific form of western music).

what i am interested in is us defining for ourselves what we do. in fact the reason the terms "hip hop" and "rap" are employed is to define and identify specific elements of music. nadir, you once asked why does rap have to be characterized as part of popular black music or an extension of rhythm&blues. why can’t rap be its own category. i think that is a very important question. rap is its own category, it’s own genre and should be celebrated as such. however, if hip hop heads want to argue that rap is just another example of the western song form, that too is a legitimate argument if one defines what one means by "song."

or, to put it another (blunter) way: most rappers can’t sing and most singers can’t rap. although a few can do both, rapping and singing are two different disciplines. each should be recognized and we should develop appropriate terminology and criteria to evaluate their respective strengths and weaknesses both on a comparative basis (i.e. rapping compared to singing) and within each discipline (i.e. what determines a good rap). it seems to me, when i listen to a song, i expect to hear a singer. when i listen to a rap, i expect to hear… ya know what i mean?

—kalamu

March 14th, 2006 at 9:06 pm

It is interesting to me this disconnect that seems to separate the generations of music. It is ironic that rap music is a powerful medium bridging several generations and genres yet there exist a gulf separating musical sensibilities between generations. However it may just be a difference in semantics. Admitedly the older generation has come across as being judgmental while expressing opinions of what is valid music and what isn’t. In reality or at least most cases it is wrong to assign other musical sensibilities to the new music as rap has to be validated and defined by those whose culture gave birth to a form of entertainment that is the most pervasive influence in the world.

The most obvious disconnect to me is the one that takes funk out of the hands of a drummer and places it in the hands of a dj. The most skillful turntablist as well as the head with the biggest ears has to admit that there is a slight disconnect in the natural flow that occurs when the chemist cuts and paste, when the dj scratches, drops beats, loops lines and bounces between tracks. I don’t care how good the technology is, to most pre- generation x’ers sensibilities, it comes off sounding disjointed and slightly out of sync. I imagine this too becomes part of the hustle. Brothers create with turntables and others turn tables selling technology. Then technology begins to direct art and culture becomes a backdrop. Life developed in a Petri dish cannot sustain itself for very long.

Before rap, Black music (even the most syncopated funk) flowed organically. The most glaring interruption being the drum machine. But even with ‘percussion in a can’ there was still a sense of flow to the new hustle. The most significant thing was that one did not have to actually spend the time and effort required to learn all of the nuances, shades, colors and voices of the drum in order to record a song. As long as the record buying public was cool with it this too was fine with producers who did not have to pay a real drummer. I imagine there are those who are content to refer to this as funk. This ‘fake it till you make it’ approach is frowned upon by some of us. I tend to look for creativity and innovation.

I once witnessed The Executioners manifest a form of musical science that broke up 4 or 5 different sampled beats and, using cuts and scratches, recreated the Funky Drummer’s solo from James Brown’s I Got Soul and I’m Super Bad. That exhibition worked for me. That brother made the connection that took what already existed a step further. I felt that dj respected the game enough to show, through, example, that it ain’t where you’re from, it’s where you’re at. He was definitely on some next shit. Don’t get me wrong, if all a person is looking for is a beat to dance to and a stupid line to quote, then perhaps Jay-Z is your man. I’m cool with that as well. Hell, I’ll even give ‘J’ points for his delivery. But me making a less than favorable comment about the Black Album does not necessarily mean I don’t get rap. I’m just not buying Jay-Z’s hustle. I’m looking for something different, something more.

Most jazz fans today including baby boomers as well as the children of the aftershock have learned the hard way that in order for an art form to remain vital and relevant it has to grow. That growth has to proceed naturally from those who love Black culture. Artist cannot expect jazz to move forward by simply varying themes on I Got Rhythm.

Where is rap music today? Where will rap be tomorrow? I’ve heard some say the rap is where the people are. That’s cool as long as it’s the people and not the industry directing the movement. The majority of Black people come from tough neighborhoods and most overcome their environment and contributes to make society better. I have yet to encounter the monolithic mutation that is part pimp/ho, hustler/junkie, murder to stay alive, fatherless crack ho with crazy back, masion dwelling/ cardboard box living, eating out of a dumpster while sipping cristol, blonde afro wearing/ cornrowed dreadlock having Black family out there. Black people may relate to some of that because they witnessed or even lived it at one point or another. That doesn’t necessarily mean that all Black people glorify this way of life. Yet these are the types of aural and visual whips that keep us disconnected by keeping the focus on the most stereotypical caricature imaginable. I understand these images may be popular ans sell units but how many times have you cringed after first seeing or hearing the new video or recording only to later catch yourself bouncing to after hearing it over and over. I know looping is a device that dj’s and mc’s use to keep bangin out the hits but damn! Do we really need to keep seeing and hearing the same shit? More often than not the health and vitality of a cultural art form is not the consideration of the business.

In light of the fact that the first generation of hip hop is headed into middle age is the realization that there are always going to have to be innovators and innovations pushing the envelope and the music as the audience grows is clear. We have all heard how some in hip hop like to claim credit for the resurgence in popularizing older forms by virtue of the fact that rap samples break beats and melodic phrases from rhythm and blues and jazz. This is a good thing – this stem cell approach to keeping old shit fertile. That is innovation. The disconnect comes in when considering a song like Amen (Brother). In the broad scope of Black music Amen is considered a classic of it’s own accord. Yet some "real hip hop heads" declare Amen a classic by virtue of the fact that a fragment of the drummer’s rhythm contains the earliest known beat that has been used over and over by dj’s ever since hip hop’s beginning. Now, me saying that this sounds like some Darwinist revisionism masquerading as hip hop history which seeks, utilizing bad science, to document the exact moment a beat becomes funk; i could see how a statement would tend to create a rift. So I will refraim from making those sorts of comments. But this declaring a song a classic using the aforementioned criteria is interesting to me though.

Brand Nubian’s Wake Up is a classic. Roy Ayers’ Everybody Loves the Sunshine, while being a nice little ditty utilized several times by hip hop performers is not a classic. The Sunshine hook like the riff from the Funky Drummer, the manner in which they are utilized in hip hop would more likely be referred to as "standard devices". Much like a drummer in jazz uses a shuffle or an 8-0-8 beat or boom bap in rap. Again I respect the right of all "real hip hop heads" to define the music however they see fit. Baby Dodds, Papa Joe Jones, Zigaboo Modeleste, and The Funky Drummer never patented beats or drum techniques. Artist Innovate and move on; it a continuum. A lot of entertainers bite claiming they "give the people what they want." However, left to their own devices all people are not going to want the same thing forever and the industry is not going to continue to "date" rap(e) forever. Ask Michael Jackson. If the "real heads" don’t take control of this thing soon then "real hip hop" is going to be buried further "underground" only to be marketed like artesian water.

Consider this, Most rap samples a form of jazz marketed as fusion. Even though this music was popular in the seventies, jazz sales were down. Wynton Marsalis arguably single handedly saved straight ahead jazz for the industry in the early 80’s. Armed with an encyclopedic command of the history of jazz, the intelligence to speak concisely and the virtuosity of a master, Wynton was both literally the face on the business as well as it’s sound and fury. Selling records and receiving Grammy’s in jazz as well as classical music, the New Orleans native proceeded to to raise millions for Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York. The trumpet/composer/band leader wen on to win a Pulitzer Prize for the multi-disc epic, Blood on the FIelds. A few years later, while still in his 40’s, Wynton didn’t even have a record contract. The music industry, as it relates to Black culture, tries to portray itself as a benevolent sponsor but history reveals her as a calculating shrew the likes of which brothers and sisters would be wise to secure both a pre and postnuptual agreement befor climbing into to bed. My reason for this stroll down memory lane is, if I am correct, a lot of hip hop heads refer to the golden era as the early to mid 80’s. It’s twenty years later.

March 15th, 2006 at 4:45 pm

I hate to admit this, but Rakim’s flow makes me tune out and forget to listen. There’s so little variance in his tones that I don’t pay attention to what he’s saying. He has some classic lines that I will always remember (notably most of Microphone Feind and whatever that song is when he says "you thought I was a donut, you tried to glaze me"), but I’ve never been a proper fan.

Baba, I think you’re being generous by saying that you had *children* who were curious about music. You had one child in particular–Mtume ya Salaam–and all of us Salaams have been massively enriched by both of your loves for music. I don’t go out of my way to listen to music. Up until the advent of ITunes I rarely listened to music at home (I think I may be a reincarnated monk), but I know an incredible amount of music due to you and Mtume’s passions.

And I know old school hip hop b/c of Mtume. Schooly D was played so very often in our house… I didn’t know you got that for Mtume.

PSK what the hell does that mean?

P for the people who don’t understand how one homebody became a man

S for the way they scream and shout, one by one I be knocking them out

K (i don’t remember what K was for), but i remember that Schooly D used to rock HARD.

Mtume says:

Kiini, the ‘glaze me’ line is from "Eric B. Is President." And maybe you couldn’t remember the line from "P.S.K." because it doesn’t make sense. Unless you spell ‘cutting’ with a ‘k’: "’K’ is for the way my DJ’s cuttin’ / Other MCs, man, they ain’t saying nothin’." … (Oh, btw. "P.S.K." actually stands for "Park Side Killers.")

April 9th, 2006 at 12:43 am

probably my favorite Rakim song. Beat made by thelate Paul C, I believe (uncredited). The first Rakim song that I really “heard”. I disagree that the album is weak…

This and Gang Starr’s “Step in the Arena” were what I used to listen to as I jogged around Allston, MA in the early 91. I still get runner’s high/lactic acid thinking about it.

Thanks..

Leave a Reply

| top |