GOODIE MOb. / “Soul Food”

And today our children wonder: what the hell happened, how could you go from a love supreme to a disco ball? —Kalamu ya Salaam, from his review of Doug & Jean Carn’s “Infant Eyes.”In his write-up of Jean Carn’s “Infant Eyes,” Kalamu asked if I remembered when our family broke up, if I remembered when he left the marriage. I do remember, of course. I was thirteen years old. It’s not the type of thing a thirteen-year-old forgets. But, Kalamu wasn’t really asking if I remembered. He knows that I do. What he was really doing was drawing a parallel between the personal breakups that occurred around that time with the larger breaking up of the alternative New African vision that he and my mother and their community of like-minded Mothers and Fathers (or Mamas and Babas, as we young people referred to them) were attempting to nurture into reality. Now that I’ve been through marriage and divorce myself, now that I know first-hand how complex and horrible the reality of breaking up can be (particularly when children are stuck in the middle), I find it impossible to put myself in my parents’ shoes. They not only lost what I lost—job, home, child, partner—they also lost the hopes and dreams of an entire generation. I know what the pain of losing a family feels like. I wouldn’t wish it on an enemy. But to lose a family and at the same time lose everything that you and your entire generation of young freedom fighters sacrificed for, worked for and (literally) bled for? It had to be devastating. (And I wonder now, which came first? Did the counter-revolutionary pressure create the fissures in the personal relationships? Or did the strains in the relationships create the opening the system needed to push its way in?) Anyhow, like Kalamu said last week: what does any of this have to do with music? Well, the moment I read Kalamu’s line about going from ‘A Love Supreme’ to a disco ball, I thought of the rise and fall of my favorite hip-hop group of the Nineties, the mighty, mighty Goodie MoB. (The group’s name is usually pronounced in two words, ‘Goodie Mob,’ but sometimes, in deference to the phrase ‘The Good Die Mostly Over Bullshit,’ it is pronounced in three words, Goodie Mo Bee.) In the span of three albums, Goodie MoB. went from giving the working-class Black community ‘food for our souls’ to giving (or attempting to, at least) the whole world a disco ball.

The Goodie MoB. story illustrates a phenomenon that has occurred time and again in America. Revolutionaries are, by definition, a threat to the system. The system is set up to implicitly and automatically combat any revolutionary action, any fight for true change. And, there are forces within the system that explicitly and directly attack any revolutionary action. Should these default defenses fail, the system has one last trick up its sleeve, and what a trick it is. Instead of fighting the revolutionary, the system does exactly the opposite. It offers the revolutionary a place at the table, a piece of the pie. It says, “We give. You win. Here, take this money and do whatever you want with it.” If one were to look back at many of the major and not so major figures of the Civil Rights Era, many ended up dead, in jail, or strung out on drugs (victims of the system’s attack mode), but many others ended up as ‘respectable’ members of society (victims of the system’s ‘trick’ mode)—politicians, businessmen and women, college professors or lecturers, all doing quite well for themselves. But as the legendary Jamaican DJ Buju Banton once sang: “Those who can run, will run / But what about those who can’t? / They will have to stay / Opportunity [is] a scarce, scarce commodity.”

The Goodie MoB. story illustrates a phenomenon that has occurred time and again in America. Revolutionaries are, by definition, a threat to the system. The system is set up to implicitly and automatically combat any revolutionary action, any fight for true change. And, there are forces within the system that explicitly and directly attack any revolutionary action. Should these default defenses fail, the system has one last trick up its sleeve, and what a trick it is. Instead of fighting the revolutionary, the system does exactly the opposite. It offers the revolutionary a place at the table, a piece of the pie. It says, “We give. You win. Here, take this money and do whatever you want with it.” If one were to look back at many of the major and not so major figures of the Civil Rights Era, many ended up dead, in jail, or strung out on drugs (victims of the system’s attack mode), but many others ended up as ‘respectable’ members of society (victims of the system’s ‘trick’ mode)—politicians, businessmen and women, college professors or lecturers, all doing quite well for themselves. But as the legendary Jamaican DJ Buju Banton once sang: “Those who can run, will run / But what about those who can’t? / They will have to stay / Opportunity [is] a scarce, scarce commodity.”

Goodie MoB.’s first two albums were for those who never did get their fair share of that scarce, scare commodity called opportunity. The albums were for those who couldn’t run. For those trapped on the wrong side of the gate when the fences went up. For those who had to stay. But by the third album, Goodie MoB. was offered, and accepted, the system’s trick. They chose to sell out rather than continue the fight. On a track from Soul Food entitled “Thought Process,” Cee-Lo anticipated this development when he rapped:

Goodie MoB.’s first two albums were for those who never did get their fair share of that scarce, scare commodity called opportunity. The albums were for those who couldn’t run. For those trapped on the wrong side of the gate when the fences went up. For those who had to stay. But by the third album, Goodie MoB. was offered, and accepted, the system’s trick. They chose to sell out rather than continue the fight. On a track from Soul Food entitled “Thought Process,” Cee-Lo anticipated this development when he rapped:

Sometimes I don’t even know how I’m gon’ eat ‘Bout twenty dollars away from being on the street Shit, you might see a nigga on TV But it’s almost like I’m rapping for free That lil’ money be gone / God damn it, I’m grown Gotta help keep the heat and the lights on…Whether the offer was literal (a new contract in exchange for ‘lightening’ the sound and mood of their music) or more likely, only implied (Goodie MoB. could easily see for themselves how much money they could make if they had a hit album like some of their peers) is ultimately immaterial. The result was the same: Goodie MoB. recorded a third album that is as phony as their first two are real. That is as light and fluffy as their first two are heavy and meaningful. That is set in a shiny, materialistic and make-believe world that is light years away from their original setting, the working-class streets of Atlanta, Georgia. What follows is a description of parallel moments in the Goodie MoB. story; as the list unfolds, it will become painfully obvious that these four brothers—revolutionary spirits to be sure—suffered the same fate suffered by my parents’ generation. Namely, the system eventually destroyed them, either by creating or by exploiting fissures in their bond. Album title:

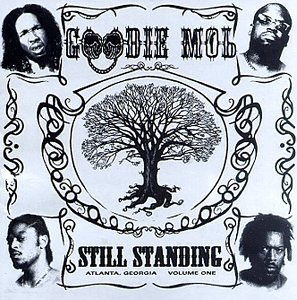

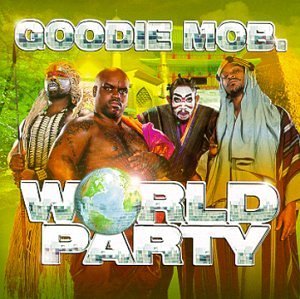

1995 – Soul Food. A double (or triple) entendré by which the group place themselves firmly within the Black community. Throughout the album, the term ‘soul food’ is used not only literally (confirming that Goodie consider themselves ‘just folks,’ as opposed to ‘stars’ or ‘performers’) but also figuratively (the phrase sometimes means ‘Mama’s cooking’—i.e., the family, and particularly the ‘Mama’ figure, is both valued and respected) and lastly, metaphorically (“Everything I did / Different things I was told / Just ended up being food for my soul.”) 1998 – Still Standing. A phrase that says: “Despite the success, and despite whatever the pressures a revolutionary group on a major label inevitably faces, we are not going away, we are not giving up the fight.” As Cee-Lo put it on the title track, “I was granted this music as my soul mate / To procreate / And give back what I was given / A life worth livin’ / And I am still standing.” 1999 – World Party. Immediately, this title indicates to me two things: 1) Via the word ‘world,’ I gather that the group is consciously seeking to expand its audience (a euphemistic way to say ‘selling out’) and, 2) via the word ‘party’ I gather that they hope to achieve this dubious goal by changing their style or lyrics or both from something earthy and real (first album) or hard and defiant (second album) to something more light and widely appealing.

Album cover:

Album cover:

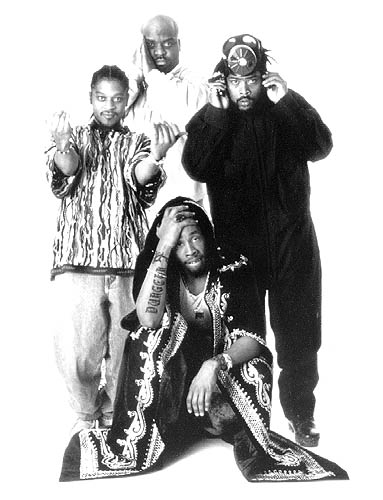

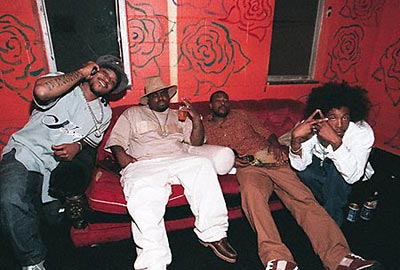

1995 – Prayer Circle. The brothers sit on the four sides of a small wooden table, their heads bowed in prayer. They are either in a family kitchen or at a soul food restaurant; on the table sits a salt shaker and a bottle of hot sauce. The brothers are dressed in ordinary clothes—their demeanor and physical appearance (bald head, cornrows, white T-shirt) suggest that they are four average members of a Black working-class community. Their feet aren't visible, but if they were, one wouldn't be surprised to see at least one pair of beat up work-boots. If there is a visual metaphor at work, it visible only by negation. Meaning, one might draw inferences about the music more because of what is not present in the picture (expensive car, expensive jewelry, objectified female, alcohol or drugs, etc.) rather than what is there (four brothers thanking the Lord for their blessings before breaking bread). 1997 – Wanted Poster. Here, unlike the first album, there is a distinct visual metaphor. The four brothers’ faces are framed in each corner of a poster which appears to be an ad for the return of runaway slaves. (I say ‘appears to be’ because nowhere on the album cover do I see ‘Wanted’ or ‘Runaway’ or anything of the like. Whether this exclusion was intentional subtlety or a concession to their record company, I cannot say.) In the center of the poster is an image of a large tree—it’s branches are ominous, it’s roots are twisted. While the cover of Soul Food is predominately muted earth-tones (indicating warmth and comfort), the cover of Still Standing is grey and black (indicating coolness, if not outright coldness). From the four corners of the poster, the brothers stare back at us either dispassionately or angrily. 1998 – Homage to Traditional World Cultures. Cee-Lo is an Indian Buddha. T-Mo is an Arab. Big Gipp, a Japanese Samurai. Khujo, an African warrior. The art is very colorful, so colorful that the images leap out at the viewer with a DayGlo immediacy. The first word that comes to mind when looking at the cover is ‘sparkly.’ For the first time, the brothers look like performers rather than ordinary people. They are ‘dressed up’: both Gipp and Khujo wear face-paint; Cee-Lo is draped in a fuchsia body-wrap; T-Mo wears an ‘Arab’ turban. Also for the first time, Cee-Lo (who would soon leave the group to pursue a solo career) is positioned in front of the other three members. The move is subtle, but Cee-Lo is clearly front-and-center. He is the ‘star.’ One other note: in the inside shots of the group, in the pictures where the brothers are dressed as ‘themselves,’ three of the four members—all except Khujo—show off platinum chains and watches, obvious signifiers of their newly-gained financial status.Group Logo:

1995 – In the place of the two ‘O’s in ‘Goodie’ are brown fists in handcuffs. In the place of the ‘M’ in ‘MoB,’ the torso and arms of a shirtless Black male. 1997 – The two ‘O’s in ‘Goodie’ are now black fists in shackles. (Note the shift from a prison metaphor to a slavery metaphor.) Inside the ‘O’ in ‘MoB.,’ there is a silhouette of a body hanging by its neck. 1998 – Both the name ‘Goodie MoB.’ and the phrase ‘World Party’ are rendered in small, shimmering ‘mirrors,’ an obvious representation of a disco ball. The ‘O’ in ‘World’ is a literal disco ball – a map of the world superimposed onto a glittering ball of mirrors. (The effect didn't reproduce well in our shot of the album cover, but trust me, it's a disco ball.)

Intro track:

Intro track:

1995 – A blues sung by Cee-Lo entitled “Free.” Sample lyrics: "Lord, it’s so hard / Living this life / A constant struggle each and every day / Some wonder why / I’d rather die / Than to continue living this way…." 1997 – A rap by Cee-Lo entitled “The Nigga Experience.” Sample lyrics: "I'm sick of lying / I'm sick of glorifying dying / I'm sick of not trying / Shit, I'm sick of being a nigga…." 1998 – Yelling in Spanglish above the whoops and cheers of a virtual crowd, MTV’s La-La introduces the title song, “World Party.” The chorus of which is an interpolation of Lionel Richie’s “All Night Long”: "Party / All night / Fiesta / Forever" (Repeat 4x)First single:

1995 – “Cell Therapy.” A now-classic tale of ghetto paranoia/future fiction. Through dark and powerful imagery, the four brothers present the 21st century future-ghetto as a place where every community is gated and serial coded, where “unmarked black helicopters swoop down,” the Constitution is permanently repealed, and “the New World plan” is “the planet without the Black man.” Chorus: “Who’s that peeking in my window? / ‘Pow!’ / Nobody…now.” 1997 – “They Don’t Dance No Mo’.” An extended metaphor that argues against the mindlessness and violence of the modern Black club scene while simultaneously and brilliantly bemoaning the absence of dancing in the modern hip-hop scene. (I say ‘brilliantly,’ because the song simultaneously argues both for and against dancing.) Chorus: “They don’t dance no mo’ / They don’t dance no mo’ / All they do is this / All they do is this.” (‘This,’ meaning standing on the wall acting hard.) 1999 – “Chain Swang.” The lyrics are indistinct – part bragging, part ‘positive,’ part threatening. But the most memorable aspect of the song (for better or worse) is the chorus: “Whether you slang ‘caine or you gang bang / Or work a nine-to-five just trying to maintain, man / Do you thang, man / It’s all the same, man / Let your chain swang / Let your chain hang.” By modern rap standards, this glorification of criminal culture and material consumption is very, very mild. By the standard Goodie MoB. set for themselves on their first two albums, it is virtual treason.Love Song:

1995 – “Guess Who.” The four brothers’ tribute to Black mothers. Each MC has a different perspective, but a common thread of appreciation and respect runs throughout. Khujo: “When I came home blurred and couldn’t find the keyhole / Guess who unlocked the doors…”; Cee-Lo: “My Mama / Destination unknown / Went out on her own / She was barely even grown…”; Gipp: “Standing in front of the two-inch glass / A woman ready to hand the cash over for her son…my Mama”; T-Mo: “Pearl, my world / What would I do without her spark? / Probably be on the street with nothing to eat.” Chorus: “I dedicate this song to you / For all that you brought me through / I know there will never be another / That will love me like my Mother.” 1998 – “Beautiful Skin.” A song made, as Cee-Lo puts it on the spoken intro, “Out of common respect, for all women.”* I like all four verses, but Gipp’s is my favorite because of the specificity and (likely) truth of his story. (I assume his verse is about his wife, Neo Soul diva Joi.) “Downtown Atlanta, checking your long legs / Got me smirking / Fixed me dinner one night, candles lit / Kinda thought you was slick / But it turned out you wouldn’t lie / Looked me in the eye / I listened….” Chorus: “God is your light from within / It shines through your beautiful skin / What they say ‘bout you ain't true / There's no me if there is no you / I hope that you understand / You got to respect yourself before I can.” 1999 – “The Dip,” “I.C.U.” and “Cutty Buddy” – All three songs are about picking up women for (presumably) one-night stands, replete with repeated references to alcohol, clubs and posteriors. Respective choruses: “You know how good it could be / If I take you home with me / I know the mood is right / I don’t wanna be along tonight / Let’s dip, shorty” and “I see you / Do you see me? / I’m staring at ‘cha” and “You can be my cutty-buddy, my hangout honey / You can be my cutty-buddy / Cutty, cutty.” (‘Cutting’ is Atlanta slang for having sex.)

In 1999, when World Party came out, I was doing a list-serve named Art Of Rap Weekly. Each week, I and three other hip-hop fans talked about a new album and I transcribed the resulting conversation. World Party was unanimously trashed, but even more than the negative reaction we all had to the album, the thing I remember most was the hurt and anger that one brother, Gerald, expressed. As we worked our way through the album, discussing the significance (or lack thereof) of the lyrics and themes of each song, Gerald grew angrier and angrier. Eventually, he was so angry, he was almost moved to tears. These four brothers had been his heroes.

Goodie MoB.’s change in style and substance was so hard to swallow not only because of the magnitude of the change but also because of the (apparent) suddenness of it. We never saw it coming.

During hip-hop’s so-called Golden Age (the late Eighties), artists like Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions and X-Clan created a sort of ‘pastime paradise.’ The images, lyrics and videos of political hip-hop were straight out of the Civil Rights Era. While I enjoyed the music, I can’t honestly say I connected fully with it. It wasn’t music of our times, for our times. Later, in the early and mid Nineties, artists like Ice Cube (on the West Coast), Nas (on the East Coast) and Outkast and Goodie MoB. (in the South) connected with me in a powerfully personal way. Here were young brothers who had both the mic skills and the consciousness to drop politically and socially relevant lyrics while rocking hard enough to capture parts of the hip-hop audience who didn’t care whether or not lyrics were meaningful. It must have both mystified and exasperated Goodie MoB. to see like-minded artists all around them going platinum and reaping the monetary rewards of selling millions while they (Goodie) continued to struggle just to get to gold status (500,000 copies sold). Goodie MoB. must have been particularly confused by the ever-increasing popularity of their musical cousins, Outkast.

For those familiar with P-Funk, we might say that Goodie MoB. was Funkadelic (gritty, loud, bluesy, abrasive) to Outkast’s Parliament (clean, quirky, more pop-oriented). Whether individually or as a group, the members of Outkast and Goodie MoB. consistently made guest appearances on each other’s recordings. Both groups were well received by critics. Initially at least, both groups were produced by Organized Noize, another part of the extended Outkast/Goodie brotherhood, the Dungeon Family. Given all of this, the four members of Goodie MoB must have had trouble understanding why Outkast albums consistently out-sold Goodie MoB. albums by a 4 to 1 margin, if not more. (Not to mention that Outkast is a duo; Goodie is a quartet. Meaning, all else being equal, the money has to be cut four ways instead of two.)

In 1999, when World Party came out, I was doing a list-serve named Art Of Rap Weekly. Each week, I and three other hip-hop fans talked about a new album and I transcribed the resulting conversation. World Party was unanimously trashed, but even more than the negative reaction we all had to the album, the thing I remember most was the hurt and anger that one brother, Gerald, expressed. As we worked our way through the album, discussing the significance (or lack thereof) of the lyrics and themes of each song, Gerald grew angrier and angrier. Eventually, he was so angry, he was almost moved to tears. These four brothers had been his heroes.

Goodie MoB.’s change in style and substance was so hard to swallow not only because of the magnitude of the change but also because of the (apparent) suddenness of it. We never saw it coming.

During hip-hop’s so-called Golden Age (the late Eighties), artists like Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions and X-Clan created a sort of ‘pastime paradise.’ The images, lyrics and videos of political hip-hop were straight out of the Civil Rights Era. While I enjoyed the music, I can’t honestly say I connected fully with it. It wasn’t music of our times, for our times. Later, in the early and mid Nineties, artists like Ice Cube (on the West Coast), Nas (on the East Coast) and Outkast and Goodie MoB. (in the South) connected with me in a powerfully personal way. Here were young brothers who had both the mic skills and the consciousness to drop politically and socially relevant lyrics while rocking hard enough to capture parts of the hip-hop audience who didn’t care whether or not lyrics were meaningful. It must have both mystified and exasperated Goodie MoB. to see like-minded artists all around them going platinum and reaping the monetary rewards of selling millions while they (Goodie) continued to struggle just to get to gold status (500,000 copies sold). Goodie MoB. must have been particularly confused by the ever-increasing popularity of their musical cousins, Outkast.

For those familiar with P-Funk, we might say that Goodie MoB. was Funkadelic (gritty, loud, bluesy, abrasive) to Outkast’s Parliament (clean, quirky, more pop-oriented). Whether individually or as a group, the members of Outkast and Goodie MoB. consistently made guest appearances on each other’s recordings. Both groups were well received by critics. Initially at least, both groups were produced by Organized Noize, another part of the extended Outkast/Goodie brotherhood, the Dungeon Family. Given all of this, the four members of Goodie MoB must have had trouble understanding why Outkast albums consistently out-sold Goodie MoB. albums by a 4 to 1 margin, if not more. (Not to mention that Outkast is a duo; Goodie is a quartet. Meaning, all else being equal, the money has to be cut four ways instead of two.)

The way I see it, World Party was Goodie MoB.’s attempt not so much to go pop, as it was to go ‘Outkast.’ The attempt failed. Goodie MoB.’s appeal was to be found in the elements of their style that didn’t work well for the pop market. Goodie was so loved by their core fans precisely because they weren’t slick. They weren’t radio friendly. They weren’t contrived. They weren’t catchy. They were more craftsmen than artists. More builders than architects. They were more saw than scissors. They told things the way they saw it, in the language they used everyday. There was a consistent blues feel to their music. Their music said, “We see the things you see. We go the places you go. We do the things you do. We are with you. We are you.” Goodie MoB. never came across as four performers lecturing down to their audience. They came across as four average brothers with a gift—brothers who would have been bus drivers or mechanics or hotel workers if they hadn’t been blessed with the ability to create music. They spoke for all the other average brothers who’s gifts lie in areas other than music (and for those who may well have been just as gifted in music, but hadn’t gotten the breaks that Goodie got). Goodie MoB. spoke for those who had no public voice.

The way I see it, World Party was Goodie MoB.’s attempt not so much to go pop, as it was to go ‘Outkast.’ The attempt failed. Goodie MoB.’s appeal was to be found in the elements of their style that didn’t work well for the pop market. Goodie was so loved by their core fans precisely because they weren’t slick. They weren’t radio friendly. They weren’t contrived. They weren’t catchy. They were more craftsmen than artists. More builders than architects. They were more saw than scissors. They told things the way they saw it, in the language they used everyday. There was a consistent blues feel to their music. Their music said, “We see the things you see. We go the places you go. We do the things you do. We are with you. We are you.” Goodie MoB. never came across as four performers lecturing down to their audience. They came across as four average brothers with a gift—brothers who would have been bus drivers or mechanics or hotel workers if they hadn’t been blessed with the ability to create music. They spoke for all the other average brothers who’s gifts lie in areas other than music (and for those who may well have been just as gifted in music, but hadn’t gotten the breaks that Goodie got). Goodie MoB. spoke for those who had no public voice.

Often, Goodie’s most profound moments weren’t ‘profound’ at all. Near the end of Big Gipp’s verse on “Goodie Bag” (from Soul Food), Gipp suddenly says, seemingly out of the blue, “Could someone please turn the lights on the 166 so I can see where the fuck I’m going?” When I first heard those lyrics, I remember laughing out loud, laughing because someone with a public voice had finally said something about these dark-ass streets we’re forced to live on. I mean, really—could someone turn on the lights? Or what about Cee-Lo’s line (from “Sesame Street,” another Soul Food track): “Thirteen and a half years old / Standing at the bus stop / Waiting in the cold / On the way to be / Degraded for a fee / So I can help get my family / Of this street….” If there was ever a more accurate description of menial labor than “being degraded for a fee,” I haven’t heard it. Then there’s the sense of community communicated by rhymes like Khujo’s (from “Soul Food”): “Tameka and Tiffany tripping and skipping rope / To the beats from my jeep / As I speak, ‘Whassup’ / From the driver’s seat”; and how about the sense of place communicated through these alliterative lines by André Benjamin (from his guest appearance on “Black Ice,” a single from Still Standing): “It was a beautiful day off in the neighborhood / Yellows and greens and blues / And browns and grays and hues / That ooze beneath dilapidated wood.”

Throughout Soul Food and Still Standing, powerful but ‘ordinary’ moments show up again and again; the messages are simple, both in wording and technique, but they are profound in the way they communicate to like-minded listeners a sense of belonging and togetherness. They say to the listener: “We know things are hard, but we’re in this together.” Perhaps more importantly, they say: “We’re going to be OK.” And if “we’re going to be OK” doesn’t sound to you like much of a message, allow me to disagree. We’ve all experienced times where we felt uncertain, or scared, or alone, and someone we believed in stepped in and said, “It’s going to be OK.” Just hearing those words is sometimes enough to change our behavior. To help us stand a little straighter, lift our heads a little higher. To help us make the right choices instead of the easy ones. To be optimistic instead of defeatist. We believed in the message, because we believed in the messengers, Goodie MoB. We believed in them for their honesty, for their normalcy, for their lack of avarice or contrivance. We believed in Goodie MoB. because they were real.

Given all of this, it is perfectly understandable why Brother Gerald was virtually moved to tears by the blindside sell-out of World Party. It really is enough to make you cry.

Often, Goodie’s most profound moments weren’t ‘profound’ at all. Near the end of Big Gipp’s verse on “Goodie Bag” (from Soul Food), Gipp suddenly says, seemingly out of the blue, “Could someone please turn the lights on the 166 so I can see where the fuck I’m going?” When I first heard those lyrics, I remember laughing out loud, laughing because someone with a public voice had finally said something about these dark-ass streets we’re forced to live on. I mean, really—could someone turn on the lights? Or what about Cee-Lo’s line (from “Sesame Street,” another Soul Food track): “Thirteen and a half years old / Standing at the bus stop / Waiting in the cold / On the way to be / Degraded for a fee / So I can help get my family / Of this street….” If there was ever a more accurate description of menial labor than “being degraded for a fee,” I haven’t heard it. Then there’s the sense of community communicated by rhymes like Khujo’s (from “Soul Food”): “Tameka and Tiffany tripping and skipping rope / To the beats from my jeep / As I speak, ‘Whassup’ / From the driver’s seat”; and how about the sense of place communicated through these alliterative lines by André Benjamin (from his guest appearance on “Black Ice,” a single from Still Standing): “It was a beautiful day off in the neighborhood / Yellows and greens and blues / And browns and grays and hues / That ooze beneath dilapidated wood.”

Throughout Soul Food and Still Standing, powerful but ‘ordinary’ moments show up again and again; the messages are simple, both in wording and technique, but they are profound in the way they communicate to like-minded listeners a sense of belonging and togetherness. They say to the listener: “We know things are hard, but we’re in this together.” Perhaps more importantly, they say: “We’re going to be OK.” And if “we’re going to be OK” doesn’t sound to you like much of a message, allow me to disagree. We’ve all experienced times where we felt uncertain, or scared, or alone, and someone we believed in stepped in and said, “It’s going to be OK.” Just hearing those words is sometimes enough to change our behavior. To help us stand a little straighter, lift our heads a little higher. To help us make the right choices instead of the easy ones. To be optimistic instead of defeatist. We believed in the message, because we believed in the messengers, Goodie MoB. We believed in them for their honesty, for their normalcy, for their lack of avarice or contrivance. We believed in Goodie MoB. because they were real.

Given all of this, it is perfectly understandable why Brother Gerald was virtually moved to tears by the blindside sell-out of World Party. It really is enough to make you cry.

After World Party, Goodie MoB. broke up. Cee-Lo went solo and has since released two acclaimed and relatively successful solo albums, Cee-Lo Green & His Perfect Imperfections (2002) and Cee-Lo Green Is The Soul Machine (2004). Khujo and Big Gipp also released solo projects (neither did well with either critics or the record-buying public) before reuniting with T-Mo to record a fourth Goodie MoB. album entitled One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show. (The title is an unsubtle swipe at their estranged brother, Cee-Lo, who happens to be both short and stocky.) Though the various albums contain sparks of goodness here and there (most often on Cee-Lo’s two projects) none of the former brothers’ solo or group efforts since the breakup have even approached the level of sincerity, honesty and good ol’ down-home Southern funk that the first two Goodie MoB. albums exude through every song.

In the end, the brotherhood’s name proved to be prophetic: the GOOd did DIE, and in all likelihood, it was Mostly Over Bullshit.

—Mtume ya Salaam

*You won't hear this line on the version in the jukebox because the posted version is the radio edit. For whatever reason, most of Cee-Lo's spoken intro didn't make the cut.

Click here to purchase Goodie Mob's Soul Food

After World Party, Goodie MoB. broke up. Cee-Lo went solo and has since released two acclaimed and relatively successful solo albums, Cee-Lo Green & His Perfect Imperfections (2002) and Cee-Lo Green Is The Soul Machine (2004). Khujo and Big Gipp also released solo projects (neither did well with either critics or the record-buying public) before reuniting with T-Mo to record a fourth Goodie MoB. album entitled One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show. (The title is an unsubtle swipe at their estranged brother, Cee-Lo, who happens to be both short and stocky.) Though the various albums contain sparks of goodness here and there (most often on Cee-Lo’s two projects) none of the former brothers’ solo or group efforts since the breakup have even approached the level of sincerity, honesty and good ol’ down-home Southern funk that the first two Goodie MoB. albums exude through every song.

In the end, the brotherhood’s name proved to be prophetic: the GOOd did DIE, and in all likelihood, it was Mostly Over Bullshit.

—Mtume ya Salaam

*You won't hear this line on the version in the jukebox because the posted version is the radio edit. For whatever reason, most of Cee-Lo's spoken intro didn't make the cut.

Click here to purchase Goodie Mob's Soul FoodThis entry was posted on Sunday, August 7th, 2005 at 12:02 am and is filed under Contemporary. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

10 Responses to “GOODIE MOb. / “Soul Food””

August 8th, 2005 at 8:58 am

Mtume, I’m sitting here trying to remember why I bought "Soul Food" in 1995. I think it would say something important about where my head was at then, but try as I might I can only remember talking about the album after I had bought it. Their song about the Red Dawgs (the para-military arm of the Atlanta P.D.) really resonated with my college friends who were from ATL, and I really dug all the soul food references. I also remember writing a paper for a youth culture course I was taking and I quoted the conspiracy theories present in Goodie MoB’s and Ice Cube’s work. To paraphrase Archie and Edith, Them were the days.

August 8th, 2005 at 10:14 am

Mtume, you all have achieved texture, with the jukebox. The rap pieces as a bridge work. I didn’t mind them at all. They must be the guys you talking about MoB. My impression is that their rap works because the lryics, the music are caught up, seasoned, and bounded by soul, I mean, community, I mean, larger than a posse or a clan. There’s more to the world beside talking shit and showing off, on an individual tip.

There are times we each as individuals need to step away from our families for a moment, even point out their shortcomings rather loudly. Well, all that’s part of growing up. Whatever failures, say, I might see in a Robeson or a Wright, I ain’t gonna crack on them without giving them their props, and their significance.

All our artistic production it seems to me if it’s gonna call itself Community, as James Brown says, It’s gotta have Soul. And I would add, it oughta swing. If rappers and poets and critics recognize that all this fronting and conflict ain’t where it is anymore. It’s how we gonna survive with the world passing us by.

There’s got to be a powerful recognition, our papas have left us a powerful legacy, powerful weapons to sustain the struggle for a thousand years. We all need some Soul Food if we gonna do it right. And it’s gotta Swing.

One more thing that’s gotta happen. We got to respect that “There Ain’t Nothing Wrong with Being a Sufferer.” There’s meaning there.

Everything ain’t everything. As Marvin intimated, There’s a Cosmic Groove. And you don’t need no degree to know when somebody ain’t in the groove. Yall aint’ got no problem yall grooving.

Rudy

August 8th, 2005 at 11:35 am

This is just a beautiful Crime Scene Investigation. As you’ve stated so well, the important and significant truth of the Goodie Mob story is that it is just another rite of commodification in our culture. That you Laid. It. Out. for us to see so well Is a blessed service to those who do give a damn. It is sustenance for resisting the forces that don’t give a damn. Soul Food Damnit!

August 10th, 2005 at 8:39 am

One of the reasons of music’s importance is the effect that it has on the spirit. You can never tell what the effect music will have on the listener. Control issues are at the root of the industry’s mode of operation. That’s why the internet is one of the best things that could have ever happened to an independent artist. Especially if the artist or performer has the fortitude to express their idealism. While some think that idealism is basically a commodity that manifested by youth I feel idealism is an unforgiving virtue. There will come times when an artist or performer has to make hard choices. And if that artist is going to be true to whatever ideals he deems important then some real sacrifices have to be made.

One of the beautiful things about jazz is that you can have Sun Ra and the Arkestra, The John Coltrane Quartet, in bold letters on a marquee or album cover and nobody gets hurt. People talk about how great Bob Marley is but can you imagine that tight band without Ashton ‘Family Man’ Barrett’s bass holding it down? In the case of Sun Ra some of his cats stayed with the Arkestra (in the same house even) for thirty and forty years and never made “rock star” money. Trane never asked Elvin to leave but Elvin chose to leave with the addition of Rashid Ali. My point is that being a musician doesn’t make a person who they are, being who they are makes an artist the type of artist they are. But, as a listener, do you want to imagine a Sun Ra band without John Gilmore, Ronnie Boykins or Marshall Allen? How about Trane’s classic quartet without Elvin Jones? I doubt it. Check out Wynton Marsalis’ Black Codes From The Underground and Live At Blues Alley. Before Sting came along and ‘appropriated’ Bradford, ‘Tain’ Watts and Kenny Kirkland. Ask Wynton how important the group is. I’m not faulting anyone for the decisions or choices made. And I ‘m definitely not trying to say anything about Wynton’s Marcus Roberts/Wes ‘Warm Daddy’ Anderson et al group. I’m just saying that in a group there is such a thing as ‘group dynamics’ at work. Being a good leader is only one piece of the puzzle. Each member has to be committed to that common goal. Because when the crossroads come – and they most definitely will come – whatever is motivating you to do what you do will be your saving grace. And if money is your main motivator, if fame is the main motivator or if you just simply love music, then that is the thing you are going to fall back on when things get rough. There is a value system at work here. Doing “menial” jobs might be hard to take but selling out is harder. Cecil Taylor was washing dishes in a NYC restaurant when Down Beat came out listing Taylor as number one piano player. You can’t value culture and pimp it at the same time. People who look for realness can sense when an artist is faking.

Nothing last forever but while they were together Goodie MoB and their production crew laid down a foundation which was revolutionary in helping to define the sound of the south in rap music. Sometimes, especially with Black culture trying to survive and thrive in a hostile environment, all you are going to get is a snapshot, a Polaroid. You ain’t gonna always have a Gordon Parks or Romare Bearden to frame that shit into a relevant and panoramic scene. Thanks Mtume.

Peace,

AumRa

August 10th, 2005 at 4:39 pm

“I don’t recall/ever graduating at all/sometimes I think I’m just a disappointment to y’all”

The Goodie Mo-B implosion broke my heart. Mtume, you have provided a fitting epitaph for this group- you KNOW how I feel about this.

Soul Food represents Atlanta for me at that time- warm summer, good food, ‘big-legged Gurls’, Elders dispensing knowledge, RBG medallions purchased at West End Marta Station…

‘Kast and Goodie were like brothers, one whom ended up in the NBA, the other whom had opened up a popular local restaurant, only to abandon it and try and join his brother in the league….WHY?

But I don’t want to dwell on World Party…it doesn’t even exist for me anymore- I think I let my Wife tape a class lecture over it or something. Soul Food though…that is up there with Brand Nubian’s ‘All For One’, A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘Instinctive Travels…’ and Pharcyde’s ‘A Bizarre Ride..’ as classic albums that didn’t reinvent the genre, but displayed a distinct, unmistakeable mastery.

So much has gone down for these cats since…Khujo almost died in a car crash and lost his leg, Ceelo went and ‘got Grown’…Gipp had a child with Joi….a lot of life lived. I don’t think we’ll see them achieve what they had in the first two albums, although I am interested to hear Ceelo when he reaches his forties to see how his voice and singing matures. Other than that, they checked out with World Party……*sigh*

August 13th, 2005 at 1:35 pm

Thought provoking commentary for real (the apple don’t fall far…). Hearing Soul Food takes me straight back to ATL and back to the feeling that maybe hip-hop could still have fresh breath.

Cee-Lo is really on some nextness, I appreciate him, but I also see what you mean about the value of the four perspectives.

But hey, as a Joi fanatic I don’t think calling her neo soul fits. I don’t know if the stint with Lucy Pearl or something on Star Kitty made you write that, but Pendulum Vibe and Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome– with that amazing Betty Davis remake– mean that in my book, Joi defies any sort of categorization.

Yeah, I know, you write brilliant commentary about Goodie Mob and I’m talkin bout Joi. ![]() True.

True.

Mtume says:

You’re right about Joi. I just called her that as a short-hand. It fell in the middle of a paranthetical reference that fell in the middle of a sentence and…. Whatever.

"If I Get Lucky, I Just Might Get Picked Up." Baaaaaaad. And what about the Labelle cover? More badness. And what about Fishbone as a frickin’ backup band?! Will definitely have to post some Joi one of these days.

November 7th, 2005 at 10:40 pm

I thought hip hop started cause people were living in fucked up situations and they needed an escape, so they go to a party and they relax and they enjoy thier life. It wasnt til the message dropped that people got involved in talking about social realities.

hiphop can be a tool for many things, but a majority of people who listen to it like to party.

Some people are dealing with hard hands. I think making one album about having a party isnt really a major crime, okay in a perfect world, they would have banded together forever and maintained this aura of artsitic credibility, but you dont know what the hell these people were facing, things in their real lifes that they may not have spoken of, you are not in their mind….maybe they do all sorts of stuff in their real lifes that is beneficial and supportive of the people, just because their album doesnt represent that, its just an album, every artist has some sort of failure in their career, you are not a member of the goodie mob.. maybe yall should stop looking to them to be some sort of heroes to you, and if you feel you need a hero, instead of looking to artists, look to the person who drives the bus, the person who works the menial job, look to yourself mange . We all human man. You think people who do work menial jobs dont go out on the weekend and party? I don’t see why yall so harsh. It would be great if every artist could get paid to be themselves, but hey, things happen. How “real” do you want them to keep it?

were they your heroes cause you saw some strength in them that you didnt have? And i fyou didnt have it, how can you hate them?

if they were just regular guys and their appeal was that were in touch with the people, how would they be above selling out? most people i know how work menial jobs would sell out in a minute. You think people like washing dishes eight hours a day?

January 25th, 2006 at 11:58 pm

i wont stoplistening to still stanidng or soul food until i have no choice

it is very emotional to me and i never admitted to myself what was lost

those first two albums could touch many people in unimaginable ways

dont let that spirit die it is “immortalized forever on wax cd’s and cassettes”

November 23rd, 2006 at 3:34 am

Thank you. Goodie Mob’s first two albums have been favorites of mine since they were released and I place Soul Food as one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time, up htere with It Takes A Nation.., Criminal Minded, Fear Of A Black Planet, etc. I was severly hurt when I haerd World Party (actually, I couldn’t even stomach listening to the whole thing) and I haven’t been able to really stand any of their solo projects. I really can’t describe what they meant to me, especially Soul Food, except that as Ceelo put it, “it just winds up being food for my soul”

October 8th, 2008 at 4:13 pm

I was just reading your article http://www.kalamu.com/bol/2005/08/07/goodie-mob-soul-food/ and I found it interesting that you started out talking about Jean Carn… are you aware of the tie that Jean Carn has with the Goodie Mob? Unless I missed it you never connected the dots… Are you from East Point as well, or is this purely co-incidence?

Leave a Reply

| top |