A Change Is Gonna Come

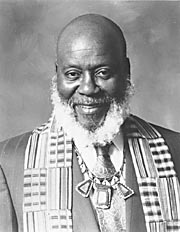

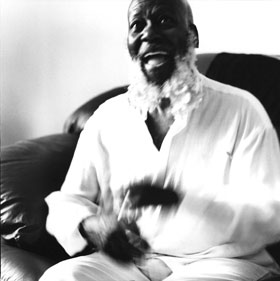

An Interview with Harold Battiste

By Mtume ya Salaam

The Neville Brothers’ version of “A Change Is Gonna Come” is one of my all-time favorite covers. I also like Sam Cooke’s original version and the Fugees remake; I wanted to write about all three, but I don’t know much—no pun intended—about Sam Cooke or his music. As luck had it at that time, every Wednesday Kalamu and I would meet up with musician-producer-arranger-band leader-teacher-record label owner-and griot Harold Battiste for dinner and conversation. I knew Harold could give me some insight into Sam Cooke’s music because of an incident that had occurred a few weeks previous.

I was hanging out in Harold’s home office, watching Harold fool around on his Mac G4 while we waited for Kalamu to show up. (A weekly occurrence; Kalamu is always late. 😉 ) I don’t remember how Sam Cooke’s name came up, but I do remember asking Harold how well did he (Harold) know him (Sam). “I knew him well,” Harold told me. “That’s his chair you’re sitting in.” Immediately, I jumped to my feet! Of course, I’d sat in the chair many times before—it’s an ordinary-looking, brown leather office chair—but now, for some reason, it felt different to sit there. It felt almost like I’d been sitting in the lap of a ghost.

I found out later (from Kalamu) that Harold not only knew Sam well but also arranged and helped Sam write his first big hit, “You Send Me.” Harold, consistent with his trademark humility and ceaseless self-deprecation, never mentioned that he was instrumental in jump-starting Sam’s career. That was a few months ago. Now, reading back over my quick transcription of our conversation, I think the conversation itself is far more interesting and potentially enlightening about Sam Cooke and his classic recording “A Change Is Gonna Come” than any drivel I would come up with. So, with no further delay….

Mtume: Was Sam really born by a river?

Harold: [Laughing.] I don’t know.

Mtume: So where did that come from? It was just a metaphor?

Harold: I don’t know. It could be that he was born by a river. I honestly don’t know.

Mtume: So it’s a metaphor?

Harold: [Laughing.] I don’t know! I already told you I don’t know three times! That’s what he [Sam] said. So why would you question that?

Mtume: I’m not questioning it. I’m just wondering if it was meant poetically or….

Harold: I just always thought of it as a metaphor or whatever you want to call it. Something like Ol’ Man River. The river’s always got a little place in folklore.

Mtume: Do you know anything about how he came up with the lyrics?

Harold: All I really remember is that during that time he was very interested and we had several conversations about the racial situation. That’s why he was willing to finance that soul station at one time. He was very much into that. And that’s why he started his own record label. He was very much into those things during that period of time.

Mtume: I don’t know much about Sam Cooke’s history. Generally speaking, did he record more music in that vein or was “A Change Is Gonna Come” pretty much the only song?

Harold: That probably was the only one. He wasn’t like Curtis Mayfield. He wasn’t doing that. He was singing love songs for his pop fans.

Mtume: Do you know if there was anything similar going on behind the scenes like when Marvin Gaye did What’s Going On? There was a whole thing going on where Berry Gordy was making comments to Marvin like, “Don’t be ridiculous. Pop radio doesn’t want this stuff.”

Harold: Sam did just one song. Which was not enough to make any people have a problem. He wasn’t overtly that kind of cat.

Mtume: What year was that? ’64?

Harold: ’64? Yeah.

Mtume: That’s the reason I was asking. I don’t know anything about the ‘60s other than what I’ve seen in books but it seems like that song was sort of, uh, I don’t know if ‘incendiary’ is too strong of a word….

Kalamu: It wasn’t strong enough [i.e., the sentiments expressed in the song weren’t overtly political enough] to be incendiary in that time period.

Mtume: You’re saying that because it’s couched in metaphor?

Kalamu: At that time, it was a ‘safe’ song.

Mtume: [Surprised.] As early as ’64? That was a ‘safe’ song in ’64?

Kalamu: Yeah! You have to understand, we listen to it today and hear the social commentary. But at that time, if someone wasn’t advocating revolution, it really wasn’t that serious.

Harold: That song was more like spiritual or gospel.

Mtume: It’s funny that I would hear the song today as being more overtly political than it sounded back then.

Kalamu: That’s because you’re comparing it to what’s on the radio today. Go back and look at the charts during that time period.

Mtume: You mean like “Ball Of Confusion” and “War” and all that stuff? I know those were hit records, but I guess I would’ve thought that [the advent of overtly political popular songs] was later. Who did “Ball Of Confusion”? The Four Tops or the Temptations?

Kalamu: Temptations. I’m not good with years, so don’t hold me to the years. But I do know the talk about “A Change Is Gonna Come” was that Sam knew he was going to die. That’s why he cut it.

Mtume: But Sam got killed, right?

Kalamu: Yeah.

Mtume: So how could he have known he was going to die if he got killed?

Kalamu: I don’t know! I’m just telling you what was being said.

Mtume: Oh, I get it. You mean like, Tupac is still alive.

Kalamu: Right. A lot of people were saying that he knew. They were taking it to the extreme. You know, to the Negro Conspiratorial extreme. [Laughter.]

Mtume: Right, right. White people have their urban myths and Black people have conspiracy theories.

Kalamu: A brother said to me the other night, “Y’all can believe that earthquake just happened if you want to, but…. [This conversation was recorded a few days after a major tsunami hit East Asia.] [Laughter.]

Mtume: [Jokingly.] That sounds about right.

Kalamu: “It was an underground atomic explosion. They were testing.”

Mtume: And you know what I love about it? Even if you know it’s ridiculous, there’s a little voice in the back of your head going, “You know what? It could be true.” … Anyway, I’m doing something on three versions of the song. The Neville Brothers’ have a version of “A Change Is Gonna Come.” And do you [Harold] know the rap group The Fugees?

Harold: No.

Mtume: Lauryn Hill used to be in the group. She rapped with The Fugees.

Harold: Oh, OK.

Mtume: They have a version of “A Change Is Gonna Come” too. What I’m saying is, that song has taken on a certain significance and I’m just wondering if y’all knew. You [Kalamu] were telling me that session musicians were going home to their wives after doing What’s Going On saying, “I just recorded a classic.” I’m just wondering if that was the feeling with “A Change Is Gonna Come” or if it’s been more over time.

Harold: No, it wasn’t like that. It was a good song and it was a meaningful song. But it wasn’t in character for Sam. It was what he felt deep down but he’d never shown that.

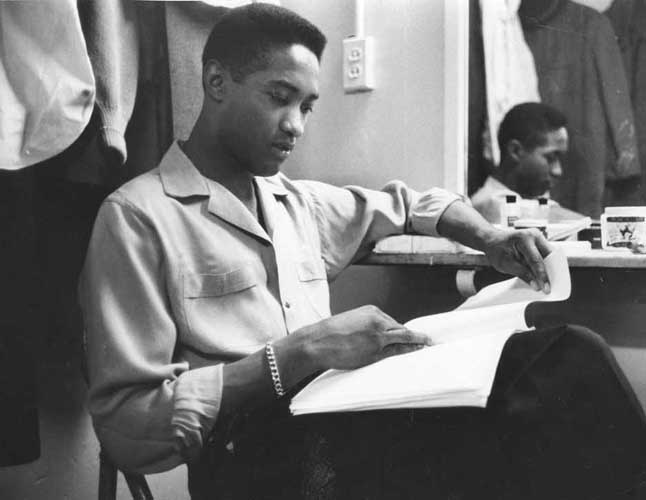

Mtume: So what was his persona?

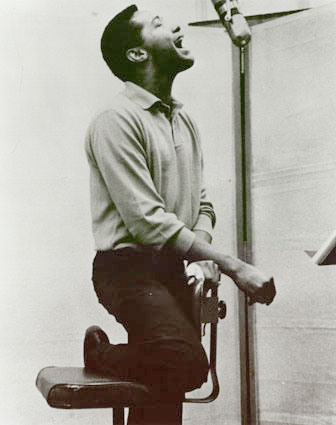

Harold: He was a matinee idol.

Mtume: A clean-cut, good-looking, ‘sing to the ladies’ type?

Harold: Yeah. He was singing to the ladies.

Kalamu: And he was smooth. That was the thing about Sam. He was so smooth that when I played a couple of his records that have blues songs on it, I had people calling the radio station saying, “That’s Sam Cooke?!” [Laughter.]

Harold: But he had those feelings. He had a lot of anger.

Mtume: You know what, you just took the words out of my mouth! The question I was about to ask you was, people talk about “A Change Is Gonna Come” as if it has a blues feel or almost a melancholic sound. But I don’t hear that. I hear anger. Even though he’s not singing in an angry tone, I hear an undercurrent of anger.

Harold: He did have a lot of anger.

Mtume: About?

Harold: Well about the whole gamut of things. The record industry. The role blacks had to play.

Mtume: In the [music] industry or in general?

Harold: In general. In general, and in particular in the industry. He was very much aware of what he thought they were doing.

Kalamu: You should make clear to him, Harold, that RCA wanted Sam exclusively but Sam carved off other portions of his career and worked with other musicians and RCA couldn’t have any of that.

Mtume: I don’t understand.

Harold: Well, like they showed with Ray Charles in the movie. Where he had the meeting?

Mtume: OK, yeah.

Harold: That’s why Sam started his own label and had his own publishing company. He was very conscious.

Mtume: So you’re saying it wasn’t just what was going on generally, with the Civil Rights movement, but it was also that he specifically saw what was going on in the industry itself. And maybe he was able to make some of those better decisions but he saw people all around him being used by the music system.

Harold: Yeah, you could say that. I used the word ‘angry’ because he was really making an effort to rectify what he could. Not that he was out on TV making statements or anything like that.

Kalamu: It was at the cusp of the Black Power movement before it really began. He was coming out of the Civil Rights movement. And the main thrust of the Civil Rights movement was to become part of the mainstream and get a piece of the action. To assimilate. But Sam and some other musicians eventually said what they really wanted was to have their own thing. And that’s a reflection of what became the Black Power movement. Sam died before he could see the national movement. But my generation, listening to his music, said that song…

Mtume: It was prophetic in a way.

Kalamu: Right. It was saying to us, “A change has got to come.” Later for this. You know? See that line about “I went to my brother”?

Mtume: Yeah. “I said, ‘Brother, could you help me, please?’ ”

Kalamu: Right. You had some of these [in a sardonic tone] Negroes…. [Laughter.]

Harold: Take a Negro and make him a Vice President. [Harold is referring to the record industry executives, not political office.] You had some Blacks who were like that. They saw what was coming.

Kalamu: Those kinds of references that resonated with the audience then, it’s not fully clear now. Nobody at that time ever thought Sam was talking about one of his blood brothers. Everybody understand that he was talking about these Negroes who are in these positions and aren’t doing anything.

Mtume: For the people.

Kalamu: Right.

Mtume: It’s a complex song. It’s not as straight-forward and direct as it seems. There’s a lot of undercurrent to it, which is why that river metaphor is a good metaphor because there’s a lot going on beneath the surface in that song.

Kalamu: Two things to put it into context. It came out right after Malcolm was assassinated.

Harold: Right after?

Kalamu: Yeah, because Malcolm was assassinated February 21st, ’64. No, ’65. It came out right before Malcolm was assassinated.

Harold: Those things that happened later kept elevating the meaning of the song.

Mtume: And then when was King assassinated?

Kalamu: ’68.

Mtume: And then Kennedy was ’70? ’69?

Kalamu: Kennedy was ’63. November of ’63.

Mtume: Oh, that’s right! Because that’s the famous “chickens coming home to roost” thing. That was about Kennedy. Of course.

Harold: And Bobby was assassinated in ’66 or something like that.

Mtume: And then the Civil Rights Act was signed in…?

Kalamu: ’64. The Voting Rights Act was signed in ’65. The March on Washington was ’63.

Harold: Malcolm was before Martin?

Kalamu: Yeah. Malcolm was in ’65.

Harold: That was a, uh, a tough decade.

Mtume: That must have been unbelievable to hear that news coming over and over like that.

Kalamu: You also can’t overlook that people were coming back from Vietnam.

Mtume: Right. Because Hendrix did “Machine Gun” towards the end of Vietnam, right? And that was New Years Day of 1970. Or New Years Eve of ’69.

Kalamu: Right. “A Change Is Gonna Come” came at a time when it reflected what was happening with society at large at various levels.

Mtume: And it sounds like you’re saying the succeeding years just served to strengthen the message of the song beyond what it may have sounded like in ’64 when it came out.

Harold & Kalamu: Yeah.

[Here’s a brief timeline of newsworthy events for the five-year period beginning January of 1963. It’s a stunner.

• 1963 – Martin Luther King makes his “I Have A Dream Speech” in Washington D.C. / John F. Kennedy is assasinated.

• 1964 – Nelson Mandela sentenced to life in prison. / Civil Rights Act passes. / Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) becomes Heavyweight Champion of the World.

• 1965 – Malcolm X is assasinated. / U.S. sends first troops to Vietnam.

• 1968 – Martin Luther King is assasinated. / Robert F. Kennedy is assasinated.

Note: The U.S. didn’t offiically pull out from Vietnam until 1973. (Although, as Kalamu says, troops were already returning from the war throughout the latter half of the Sixties.)]

Mtume: I was thinking about “What’s Going On.” That record was asking, “What’s going on? Right here, right now.” But with Sam, it was more of a foreshadowing.

Harold: It was a prophesy.

Mtume: Yeah, that’s one of those songs—there’s not too many of them—like “Get Up, Stand Up” by Bob Marley or… Actually, Bob Marley didn’t write that. I should say Peter Tosh. [Laughter.] As soon as you [Kalamu] looked at me like that I realized what I was saying. But what I was saying is, it’s hard to put into your mind that someone actually sat down at a piano or picked up a guitar or was driving down the street or whatever they were doing and actually wrote that. It seems like something that had to already have been down. The opening lines of those songs are so incredible. You say, “Who could’ve composed this?” Maybe the artists themselves feel that way.

Kalamu: That’s why I always say the movement of the people leads the art and then the art reinforces the movement. It’s not the other way around. The artists don’t create the movement. But they do give it a broader or more popular form. But you have to have a movement.

>End<