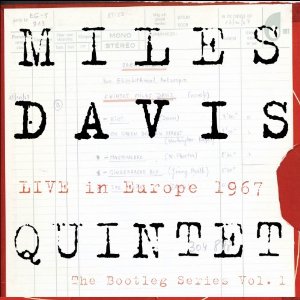

MILES DAVIS QUINTET / Official Bootleg Miles Mixtape

This is music from what many of us consider Mile Davis’ greatest jazz band: the quintet with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. This is also hours of previously unreleased music and even a concert DVD. Live in Europe 1967 is pivotal in jazz history.

John Coltrane died July 17, 1967. Trane was the only rival Miles had as the supreme jazz musician of the sixties.

This is music from what many of us consider Mile Davis’ greatest jazz band: the quintet with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. This is also hours of previously unreleased music and even a concert DVD. Live in Europe 1967 is pivotal in jazz history.

John Coltrane died July 17, 1967. Trane was the only rival Miles had as the supreme jazz musician of the sixties.

“Trane was on a search, and his course kept taking him farther and farther out…he was expressing through music what H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panthers and Huey Newton were saying with their words, what the Last Poets were saying in poetry. He was their torchbearer in jazz, even ahead of me…I had been it a few years back, now he was it and that was cool with me.” —Miles Davis, quoted in the liner notesExcept Miles was serious about being a leader, about figuring out new directions, and as always, Miles recognized that in the world of jazz, a world of improvisation and collaboration, in order to really do anything substantial one needed comrades, musicians equally, if not more so, dedicated to creating new and challenging music. When Coltrane left Miles in 1959, Miles retreated into the tried and true while trying to find a saxophonist to replace Trane. Of course there was no one. Although Sonny Stitt, George Coleman, Sam Rivers, Hank Mobley were among the many aspirants, each had their own strengths and made significant contributions but none of them fired up Miles the way Trane had. And it wasn’t just the soloing. Look at the repertoire. For the most part all the Miles Davis bands after Trane and before Wayne, all of them played old material, but then came Wayne. By 1967 the great quintet was entering its fourth year as an established ensemble—and that was a long time for a Miles Davis band with permanent personnel. These men knew each other, knew each other’s personality quirks and subtleties, were fully aware of each other’s body language, could instantly hear and respond to the portent of micro-moves in phrasing, they really, really knew each other and could shift the music in a split second to both anticipate and reflect a kaleidoscopic approach to music making, pirouetting in tandem as though doing a collective pas de deux. They could play the shit out of old shit, but these cats were also wizards at creating something new. Initially they simply turned the old songs inside out, reshaped the harmonic structures, often resorting to the surgery of elimination rather than the spectacle of adding more and more elements. In this context, new material created to build on the band’s collective extra sensory perception was the scientific alchemy that enabled Miles to hit new heights both in his personal performance and in the collective performance of his band. This was the phase when Miles’ trumpet chops were at their maximum in terms of range and velocity—the whisperer could also scream like a demon. A cool icon whose career had been built on subtlety was now also playing with blowtorch intensity. And as significant as the above mentioned considerations are, there was one other major element: this sophisticated sound proved intellectually challenging and not just emotionally stimulating. Whereas rhythm was behind all of the music of that era, most of the competing jazz bands did not have the wide range and profound harmonic depth that this unit seemingly effortlessly displayed. The complex chords flew by so fast, for many listeners it was probably as daunting as a tourist trying to follow a furious debate in a foreign language. On top of all of the intellectual mastery they also swung like crazy thanks mainly to the dynamic time keeping and time freeing combination of bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams who between them did the impossible, they kept the music in the pocket based in large part on Carter’s unerring harmonic anchor and simultaneously let it all hang out propelled mainly by Williams off kilter and captivating percussion accents. This wonderful music was preserved in large part because of the combination of George Wein’s perception as a producer combined with European respect for the artistry of jazz. Wein put together tours that featured a broad swath of jazz from early traditional to the most recent avant garde. Those tours, sold as a package, promoted the best of a broad range of musicians. In Europe, state and municipal agencies would record, broadcast, and preserve many of these performances. Even the minimum audio fidelity was at a high professional level that compared favorably to most live recordings then being produced in the USA, except on the home-side of the Atlantic ocean most of this jazz, viewed as non-commercial, was either niggardly recorded or not recorded at all. Even though this is the band that gave us the major studio works E.S.P., Miles Smiles, Socerer, Nefertiti and Miles In The Sky, other than the early Live At The Plugged Nickel (1965) set, there are no official USA-based live recordings from this the longest lasting of all of Miles’ quintets. America regarded jazz as nigger music and treated its documentation and preservation as it did the people chiefly responsible for the creation of jazz, which is to say the music was either exploited or neglected. Were it not for George Wein and European respect for jazz all of this music would have been long gone, vaporized into the atmosphere and into the consciousness of those who were fortunate enough to hear the original performances. For this October/November 1967 tour, the repertoire remained constant with few variations from tour venue to venue. Davis’ “Agitation” and Shorter’s “Footprints” and “Masqualero” were now standard at each concert, complemented by Monk’s “ ‘Round Midnight.” What these guys did with the material was the real difference as their arrangements and treatments of the music metamorphosed from night to night. The 1967 Miles Davis quintet was a marvel of modern music: cool on the surface but oceanic in their power and undercurrents. Even a quick, causal listen confirms that we should be deeply appreciative that this music is still with us in recorded form. This is why I highlight the provenance of European respect and recording of America’s greatest contribution to world culture. Even in cinema and despite Hollywood’s obvious dominance, there are widely recognized major filmmakers from all over the world. In jazz, in terms of the development and advancement of the artform, there are no universally recognized musicians who were not either born in the USA or who did not migrate to the USA to advance themselves. All of the above is the social and musical context not often discussed when talking about classic jazz recordings. In the case of this Miles Davis music, hopefully this brief discussion helps one and all to appreciate both the depth of this music and our extreme good fortune that the music is now available for all to hear. Live In Europe 1967 – The Bootleg Series Vol. 1 is a three CD + DVD, 4-disc set and is totally worth your investment of time and money. —Kalamu ya Salaam

Live In Europe 1967

01 “Agitation” (Copenhagen)

02 “Footprints” (Antwerp)

03 “ ‘Round Midnight” (Antwerp)

04 “Masqualero” (Paris)

05 “On Green Dolphin Street” (Antwerp)

06 “Gingerbread Boy” (Antwerp)

07 “The Theme” (Antwerp)

Live In Europe 1967

01 “Agitation” (Copenhagen)

02 “Footprints” (Antwerp)

03 “ ‘Round Midnight” (Antwerp)

04 “Masqualero” (Paris)

05 “On Green Dolphin Street” (Antwerp)

06 “Gingerbread Boy” (Antwerp)

07 “The Theme” (Antwerp)

This entry was posted on Monday, October 31st, 2011 at 8:21 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |