MILES DAVIS / Last of the Cool Miles Davis Mixtape

Human beings have been recording and reproducing their sound-making since 1877, when Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. The vast majority of these sound recordings have been recordings of music, or as we call them today, 'records.' That's well over one hundred years and millions and millions of records. Beginning when I was 12 years old, I spent the majority of my free time listening to as many of these 'records' as I could, still, I've heard only a small fraction of the millions. Let's call it 20,000 or so. Of the 20,000 albums I've heard in my lifetime, I want to tell you today about the one I like best. It may not be one in a million, but for me at least, it's one in 20,000.

The oddest thing about my choice (given the other albums I'd likely put in my personal top ten) is that the album has no words. Second only to my love of music is my love of words. I don't mean books necessarily. I love everything about words: the rhythms of speech patterns, the art of linguistics, the unlikely attraction of profanity and slang, the vagueries of penmanship, the specificities of fonts, anything related to words. In fact, for the first ten years of my record collecting, I don't believe I bought a single record that didn't have words.

I can still remember not only the first wordless album I ever purchased but also the circumstances surrounding the purchase. The circumstances were my asking my Baba (for those who don't know, 'Baba' means 'father' and I'm referring to Kalamu) for a recommendation of a "good jazz album for someone who doesn't know anything about jazz." At the time, I worked at Tower Records; I therefore found it both ironic and amusing that the album he suggested was the same one I'd been suggesting to customers for years. Of course, my Baba's selection was based on decades of music knowledge, jazz music in particular. He intentionally suggested an album that was both brilliantly rendered yet immediately accessible. As for my reasoning, it had nothing to do with jazz knowledge (of which I had none then and have relatively little today). I was following what I like to call 'The Elvis Principle.' You know the one - the one that says 8,000,000 Elvis fans can't be wrong? During my time at Tower, the jazz album my Baba suggested I listen to had sold so consistently and to such a variety of people, that I figured it had to be good...or at least, likeable.

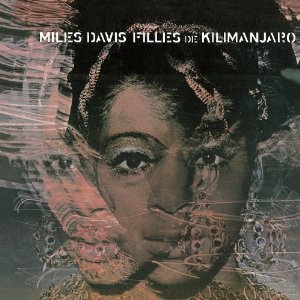

The album is Miles Davis' Kind of Blue. Several years and perhaps twenty or so Miles Davis albums later, I stumbled across another Miles Davis album, Filles De Kilimanjaro. It was love at first…umm…spin.

Miles and company recorded Filles at a crossroads. The musicians are the same five that had been playing together, to great acclaim, for the many years previous. [This bit and some of the following is historically inaccurate. I’m leaving it in for two reasons. One, because I actually believed it at the time. And two, because it’ll give Kalamu something to talk about. Go for it, Baba. ;-) ] The quintet had experimented with electric instruments before, but Filles is the first Miles album that we may truly consider 'electric.' It is also the last that we may truly call 'jazz.' (At least in the traditionally accepted definition of the word.) Clearly, Miles was becoming bored with the acoustics of, well, acoustics. He wanted the volume, sustainability and (to be honest) popularity that only electric instruments can provide.

Members of Miles’ second classic quintet—Herbie Hancock (Fender Rhodes piano), Wayne Shorter (tenor saxophone), Tony Williams (drums), Ron Carter (electric bass) and of course Miles himself—are present for most of the tracks, but they’re doing something new. And, because change was Miles' way (and because the coming changes were already in progress), they knew that these sessions were among the last they'd ever play together as a quintet. I believe these circumstances—the ‘newness’ of the style of music-making combined with the tension of the impending changes—help make Filles the beautiful recording that it is. And let's not forget the engineering. Nearly four decades later, the acoustics still grab me by the gut. The thick warmth of the electric bass. The crystalline clarity of the electric piano keys. The rolled-off effect that mutes the drums. The sharpness of Miles trumpet. The sweetness of Shorter's tenor. The almost chamber-like quiet of the background. Something in the way this recording was produced makes it sound like the quintet had to be playing in the dark. Filles De Kilimanjaro is the sound of perpetual night.

About great records it's sometimes said that 'the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.' (In fact, I've been known to say it myself.) By that, the writer or speaker usually means that each musician or each musical element contributes something different to the recording, but that the recording seems to take on a life of its own, fleshing itself out, filling its own empty spaces, becoming something that none of the individuals musicians or elements could so much as approximate alone. It's a wonderful sentiment. I've heard my share of records that exemplify the statement and I tend to like them a lot. Filles De Kilimanjaro isn't one of them. This music is very obviously the result of separate musicians. The separation is virtually audible. There is no 'wall of sound' effect. No 'greater whole.' Indeed, it's possible to listen to the entire album from the piano's point of view. Or the drum's point of view. Etc.

All five musicians are working in concert, playing variations on the same theme, but they aren't going for a unified sound – instead, they are consciously expressing different points of view. Which makes the moments when all five musicians do play 'together' all the more thrilling. For example, the 10:58 mark of "Tout De Suite." But before the moment, some background.

“Tout De Suite” begins with the entire band collaborating to produce the main theme. But at 2:30, something happens. It's as if the arrangement, the agreed-upon set of guidelines, fissures. Just plain goes to pieces. Herbie begins to pick out notes on the Rhodes seemingly at random. Ron repeats the same (or similar) series of notes on his electric bass, but he makes no attempt to create a groove. Freed from his usual job of anchoring the rhythm section, Williams sounds like a kid (which, at 24 years of age, he almost literally was) let loose in a drum store. He slaps away at the snares and cymbals, creating curious and complicated patterns while riding the hi-hat as if he's trying to set a record for most quarter-notes played in a single tune. There follows a series of intense and searching solos from first Miles, then Shorter, then Corea, but nowhere do we get a sense of unified coherency.

Then, at exactly 10:58…. I don't know how they made the sound – perhaps it's Hancock, Carter and Williams doing some small thing simultaneously, or it may be nothing more than an electronic effect or a tape trick. In any event, there's a pronounced 'shwip!' that sounds like a cassette briefly running backwards, and then, just like that, the band (who've gone their separate ways for nine minutes) suddenly begins to play the theme again. That sound, which doesn't come until eleven minutes into the tune, might just be the most singularly beautiful moment in my entire record collection.

As much as I love "Tout De Suite," it isn’t my favorite tune of the album. That honor goes to "Mademoiselle Mabry," Miles’ tribute to his one-time wife, Betty. (But we’ve featured “Mademoiselle Mabry” before, so I won’t make it the feature.) As in the case of "Tout De Suite," the tune begins with Chick Corea and Dave Holland (who were replacing Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter, respectively) repeating the deceptively simple melodic theme. They play the notes in such a deliberate fashion, that each seems to hang in the air. Eventually, Williams joins them, mallets in hand. Every few measures, Williams adds the metronomic 'tick-tick-ticking' of his high hat followed by a wash of cymbal sounds. It's a full three minutes before we finally hear from the man whose name appears above the title. But oh…! Miles four-minute solo – from 3:00 to 6:46 – might just be the most expressive of his career.

At the nine-minute mark, Shorter steps in. In typically Shorter-esque fashion, he begins by reaching deep down into the bass register of his horn, then letting loose with a flurry of rapidly ascending notes that somehow sound both passionate and serene. Williams, Corea and Holland lock down the groove, somehow sustaining the delicate tension of the almost painfully-slow groove for over sixteen minutes. Sometimes, I listen to this record in amazement, marveling at how Corea and Holland play the same brief series of notes for sixteen minutes (sixteen minutes!) without changing a thing. The only break in the tension comes from Williams' infrequent cymbal strikes. (But don't bother listening for them--they're effectiveness is due in large part to the element of surprise.)

Listen to this song in the dark, paying particular attention to Corea's piano and Holland's bass, and the conventional concept of time evaporates, allowing this sublime piece of music to last near-to-forever yet not even close to long enough. When the song finally ends—and unfortunately it, like all things, must—it ends with the same sublime perfection with which it begins. For no discernable reason, Miles simply quits playing, mid-solo. Williams strikes the cymbals three times. Corea and Holland play the exact same series of notes they've been playing for the previous sixteen minutes. And the record stops.

—Mtume ya Salaam

COOL ASS MILES DEWEY DAVIS

I agree with you that Filles de Kilamanjaro is not only great music, the album is also a major milestone and signifier in the dazzling journey that was Miles’ musical career. Filles is more than a crossroads, it is the last of the cool, the death of the cool. I mean this in the same sense that Miles’ Birth Of The Cool is celebrated as the genesis of that movement, so too Filles is that movement’s 'revelations'—the last statement opening us to further questions but paradoxically offering few certain answers for adherents of the cool style.

A few quick comments: You correctly heard and noted the sound of the electric bass. This album is one of the few times I can recall hearing Ron Carter playing electric bass.

The album Filles is actually a composite of two different recording sessions released as one statement. “Petits Machins (Little Stuff)” – June 19, 1968; “Tout De Suite” (alternate take) and “Tout De Suite” – June 20, 1968; and “Filles De Kilimanjaro (Girls Of Kilimanjaro)” – June 21, 1968, all feature the last great quintet: Miles, Wayne, Herbie, Ron and Tony. “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)” and “Frelon Brun (Brown Hornet)” – September 24, 1968, feature the transitional quintet in which Chick Correa is on keys and Dave Holland on electric bass, along with Miles, Wayne and Tony.

In any case, Miles was not simply transitioning to another quintet. Classic combo days were over, within a year the sound would be overwhelmingly electric and polyrhythmic with the addition of Airto Moreira, and later James Mtume. And that electro/percussion line up fed directly into the rock energy that occupied the majority of Miles’ recording career post-Filles.

Alas, even though he commandeered Charles’ Lloyd’s band (Keith Jarrett on keys and Jack DeJohnnette on drums), among black audiences Miles was never able to become as popular or sell as much as Herbie when Herbie turned to funk. And at the risk of being totally misunderstood, it is important to realize that after Bitches Brew, Miles Davis recordings were never as influential as those of some of his former sidemen, especially the Zawinul/Wayne Shorter Weather Report collaboration, and the aforementioned Herbie Hancock Headhunters and beyond forays.

After Bitches Brew Miles Davis was through as far as shaping the future of music. Miles had abandoned mainstream jazz, had never been heavy into the avant garde, was more a legendary figure than a real influence in rock music, and was never a major force in funk music. I understand that some acolytes point to On The Corner and a couple of other albums as influencing the aesthetics of some rap producers, however without denying a contribution, on the basis of rap recordings from that period, Miles did not significantly influence the direction of rap.

I know that assessment sounds extreme but facts is facts. Did Miles produce anything after Bitches Brew that was absolutely essential to understanding post-World War 2 musical developments?

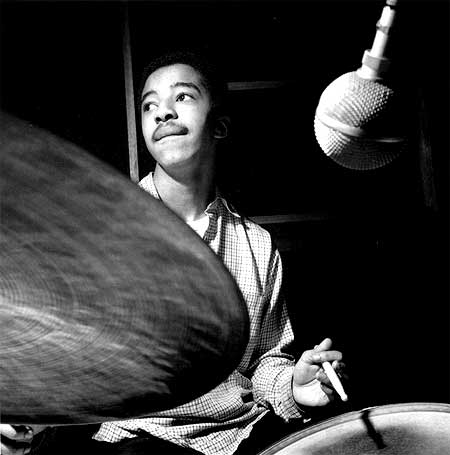

Now back to Filles. Dig, Tony Williams is the main voice keeping this music moving. I’ve heard and studied a lot of drummers, but as far as inventiveness on the drum kit in a jazz combo setting the award has to go to the young mister Tony Williams who was playing the drums as though it was a synthesizer eliciting not only all matter of textures but also advancing the melodic sound of the music. He gave the music a true floating character—flitting like a dragonfly but dropping bombs like a B-52. Tony made you listen because his drumming was the actual lead voice.

Miles may have been captain of the ship but, check it, Tony was the whole damn ocean, and everybody know it’s not the size of the ship that rocks the boat, it’s the motion of the ocean. BTW, if you go back to Tony’s 1964 debut as a leader on Blue Note Records, the beautiful Life Time recording, you can hear where he was coming from. This music did not just happen, nor was it some stuff that sprung fully formed from Miles’ mind. Connect the dots people.

Tony is not keeping time, he is not being a traditional jazz drummer, he is being an instrumentalist who improvises throughout, surprising us, not with beats but with beautiful percussive patterns. Listen to what he does on "Mabry," especially how he offers a completely different texture for Wayne’s solo. Behind Miles it had been all mallets and tom toms and the strings off on the snare, but for Wayne the strings are back on the snare with the hardness of sticks providing a solid percussive attack. Indeed, it’s hard to listen to everybody else because Tony is playing asymmetrical patterns full of unexpected accents. You keep wondering what he will do next—a veritable sea of percussive sounds, swelling, rolling, ebbing, flowing, like I said: an ocean.

Third, and I will (maybe) get deeper into this at another time and offer my evidence, for now I’m just going to drop it. 1. Birth of the Cool was the beginning. 2. Sketches of Spain was the zenith. 3. Filles de Kilamanjaro was the culmination of a trademark contemplative and harmonically rich sound we know as “cool,” a sound that took great pleasure in dredging up, examining, and ultimately both celebrating and surviving some of one’s most painful personal memories. That old R&B cliché is entirely appropriate here: it hurts so good.

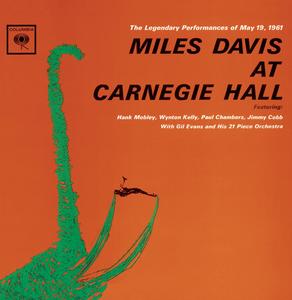

In keeping with that particular 1-2-3 timeline of the cool I present a track most of us have not heard. The track is from Miles Live At Carnegie Hall with Gil Evans, an album that almost didn’t happen because Miles tried to nix the shit for whatever reason—maybe in sympathy with Max Roach who was waging a protest against the event organizers. So although Columbia had previously planned to record live, Miles called off the recording, except engineer Teo Macero was as stubborn as Miles and used the onstage mikes to record from the soundboard. Audio-wise it’s the worse sounding album of Miles on Columbia, music-wise it’s a brilliant summation.

I’m not saying this is better than listening to Miles Ahead or Sketches of Spain but I am saying that this live version of "Aranjuez" is absolutely sublime.

Miles never fully shook his petit bourgosie upbringing, hence is expensive taste in the accoutrements of wealth such as elite foreign automobiles, high fashion clothing, and yes, trophy women. Regardless of his public persona, Miles Davis was never a street cat without formal education who survived by relying on mother wit.

Just to drop one irony on you in this regard: check that Wynton Marsalis’ new release is a collaboration with ‘master blues guitarist’ Eric Clapton and they do some traditional New Orleans style music. What are you saying Kalamu? Well, what about recording with the cats in New Orleans who are direct descendants of that music, the ones struggling to maintain the flame. And in case you need a couple of quick names: Walter Washington and Carl Leblanc.

And make no mistake, I am not condemning Wynton for recording with Clapton, nor am I condemning Miles for recording with Gil Evans; I am pointing out the petit bourgoisie penchant for choosing Euro-centric forms within which to express their artistic creations. Check it both Miles and Wynton garnered national recognition by recording European classical music. Yes, their recordings were brilliant and killing, but that does not obviate the reality of the origins.

The age-old truth about our people is our ability to adopt and adapt other cultures thereby creating not only something new but also creating incredibly beautiful hybrids. Hendrix envy notwithstanding, Miles Davis was a master of sophisticated cool jazz, and was never a master of rock or funk. The beauty of Bitches Brew is that the recording ushered in the fusion movement, which ushered to the frontlines musicians and forms that never otherwise would have been considered jazz. I say ‘beauty’ because the immense strength of black music is that the music can genuinely make room for everybody regardless of their ethnic or class background.

Fusion music with its heavy backbeat never intended to swing, moreover in the long run as all the jazz fusion records make clear the predominant influence became rock rather than funk. Many of us old jazz heads have major issues with fusion jazz, not the least of which is the absence of swing but like Courtney Pine said about some Eastern European jazz cats, they had no intentions of swinging. And that’s ok, that’s their prerogative.

We don’t have to trash post-Bitches Brew Miles because we love cool Miles. To quote another R&B cliché: different strokes for different folks. I don’t disparage fusion Miles, I just don’t dig it. I wear my allegiance on my sleeve: cool Miles for me, and except for the live recordings from Trane’s last tour with Miles, I’ll take the music of the second great quintet quick as a Tony Williams heartbeat.

Just as Miles never found a second horn voice to match either Trane or Wayne, after Tony Williams there was a barrage but no match in terms of subtly shifting the music. Make no mistake Jack DeJohnette is a powerful and beautiful drummer but a great lake is not the ocean.

BTW, newly released Miles Davis recordings of that second great quintet are about to be released—more on that in a minute.

Finally, Mtume, as a gift to you, I added to the Mixtape an alternate version of "Tout Suite," which is taken at a slightly slower tempo. I think the solos in general are tighter on the master take, but the alternate has its own sensual beauty. As far as I’m concerned, after Filles, Miles Davis the master trumpeter takes a backseat to Miles Davis the innovator who was searching for new directions in music.

Although Miles had a whole bunch more to offer, as a trumpet stylist this was the last hurrah—the last of the cool. After Filles it was into the hot, into some other kind of/different kind of vibe whether you could dig it or not. But no more hip, tortured, acoustic trumpet solos that left you sitting in the dark, tear streaks on your inner face, contemplating some unforgettable emotional catastrophe that indelibly pockmarked your internal heart, the one that most people never ever felt, saw or heard, that heart that Miles’ horn unlocked with the brilliant cobalt blue trumpet sound of the cool.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Cool Miles Davis Mixtape

Filles de Kilimanjaro

01 "Tout de Suite"

02 "Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)"

03 "Tout de Suite [Alternate Take]"

Miles Davis At Carnegie Hall

04 "En Aranjuez Con Tu Amor (adagio from Concierto de Aranjuez)"

This entry was posted on Wednesday, September 21st, 2011 at 3:28 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

3 Responses to “MILES DAVIS / Last of the Cool Miles Davis Mixtape”

September 22nd, 2011 at 8:18 pm

Guys you’ve got to check out James Mtume and Stanley Crouch in a debate about Miles Davis. Very Interesting.

September 26th, 2011 at 6:01 pm

Dear Sir(s)

Cheers from the Motherland (Ivory Coast West Africa)

I have to say many thanks

You people are our very dear and private library of congress

This here music is caviar for the ears and the soul.

P.S. i won’t add my 2 cents to the discussion cause I just can’t be objective when it comes to M&M (Miles and Mingus). i love them too much unconditionally, (even their not so good pieces move me in one way or another).

Again many many thanx

Leave a Reply

| top |