MILES DAVIS / “Miles Plays Standards”

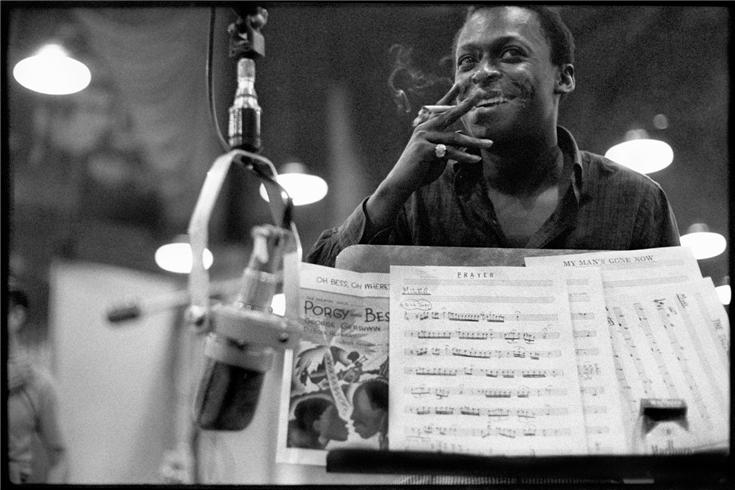

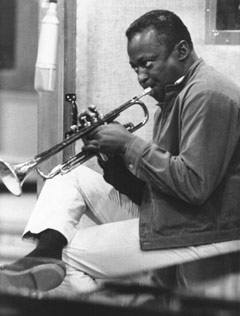

Miles. 1960. I was in eighth grade and checking out Mad Magazine (satirical funnybook with Alfred E. Newman as the lead character/mascot and his motto was “what, me worry?”). There was a faux ad for air conditioners with a smiling black man holding a trumpet and a caption something like “blows cool.” I didn’t get it. Had to ask Edward Wiltz (who played trumpet in the school band) who was that man with the horn and what do they mean "blows cool"? Within a year, I was fully up to date.

Miles. 1960. I was in eighth grade and checking out Mad Magazine (satirical funnybook with Alfred E. Newman as the lead character/mascot and his motto was “what, me worry?”). There was a faux ad for air conditioners with a smiling black man holding a trumpet and a caption something like “blows cool.” I didn’t get it. Had to ask Edward Wiltz (who played trumpet in the school band) who was that man with the horn and what do they mean "blows cool"? Within a year, I was fully up to date.

Miles was always a trend setter. Yeah, he was a musician but I believe he also kept a sharp eye on history. His first major historic move was, of course, Birth of the Cool featuring hot drummer Max Roach and a band full of white musicians playing in what quickly became known as the cool style. I never cared too much for that recording.

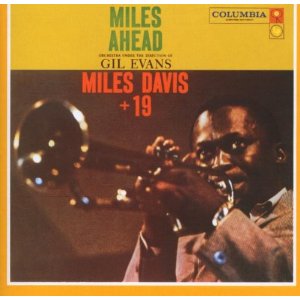

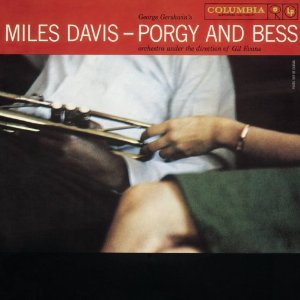

But I did dig Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and, of course – of course, Sketches of Spain. Those were the real cool records that I totally dug. All them West Coast trumpeters were boring except for the wunderkind Chet Baker, who was from Oklahoma, or some place Midwest like that. In later years as Chet's sound matured I liked his music and when I saw the documentary on Baker (Let’s Get Lost, or some title like that), I understood. All those cats wanted to be cool like Miles but their lives were not like Miles’ life, no matter how much smack (heroin) they might shoot up in imitation of black life, or rather in imitation of how they perceived black life.

Along with thousands of other jazzheads, I really snapped to attention when Miles put together that first great quintet: Red Garland on piano, Philly Joe Jones on drums, the uber-magnificient Paul Chambers on bass, and monster-man John Coltrane on tenor. That was the band that defined post-bop "progressive jazz," completely pushing aside the Modern Jazz Quartet, which, if you think about it, had been Miles’ main roadblock in terms of Miles being the king of cool jazz.

The quintet with Trane, often known as Miles’ first great band, did a hip, alley-op slam dunk. Rather than trying to out-cool the MJQ, they came with post-bop fire and blaze. Moreover, they were totally unlike that hip music for yatching that was the trademark sound of Miles with Gil Evans. Note: the first cover for Miles Ahead had a picture of a white woman on a yatch, sailing in the breeze, or something like that. The quintet with Coltrane was for hipsters of whatever hue, forget about the country club set.

Instead of exotica and leisure class play, this band was workin’, steamin’, playin’ and relaxin’. This was, yeah, five on the black hand side rather than polite finger snaps of the inner hand beige beatnik clique or the upper Manhattan well to do who liked jazz as long as the blackness of the music was surrounded by classical sounding arrangements. And this is where we pick up on Miles for this week’s BoL.

Miles was always a trend setter. Yeah, he was a musician but I believe he also kept a sharp eye on history. His first major historic move was, of course, Birth of the Cool featuring hot drummer Max Roach and a band full of white musicians playing in what quickly became known as the cool style. I never cared too much for that recording.

But I did dig Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and, of course – of course, Sketches of Spain. Those were the real cool records that I totally dug. All them West Coast trumpeters were boring except for the wunderkind Chet Baker, who was from Oklahoma, or some place Midwest like that. In later years as Chet's sound matured I liked his music and when I saw the documentary on Baker (Let’s Get Lost, or some title like that), I understood. All those cats wanted to be cool like Miles but their lives were not like Miles’ life, no matter how much smack (heroin) they might shoot up in imitation of black life, or rather in imitation of how they perceived black life.

Along with thousands of other jazzheads, I really snapped to attention when Miles put together that first great quintet: Red Garland on piano, Philly Joe Jones on drums, the uber-magnificient Paul Chambers on bass, and monster-man John Coltrane on tenor. That was the band that defined post-bop "progressive jazz," completely pushing aside the Modern Jazz Quartet, which, if you think about it, had been Miles’ main roadblock in terms of Miles being the king of cool jazz.

The quintet with Trane, often known as Miles’ first great band, did a hip, alley-op slam dunk. Rather than trying to out-cool the MJQ, they came with post-bop fire and blaze. Moreover, they were totally unlike that hip music for yatching that was the trademark sound of Miles with Gil Evans. Note: the first cover for Miles Ahead had a picture of a white woman on a yatch, sailing in the breeze, or something like that. The quintet with Coltrane was for hipsters of whatever hue, forget about the country club set.

Instead of exotica and leisure class play, this band was workin’, steamin’, playin’ and relaxin’. This was, yeah, five on the black hand side rather than polite finger snaps of the inner hand beige beatnik clique or the upper Manhattan well to do who liked jazz as long as the blackness of the music was surrounded by classical sounding arrangements. And this is where we pick up on Miles for this week’s BoL.

We open with two Miles and Gil Evans tracks. This is the caviar of cool jazz, they might as well have even put instructions for how to make a dry martini on the back cover of Miles Ahead. And, of course, that hip, hip, swinging version of "Summertime." Philly Joe’s rim shots are down in the mix but no problem because Paul Chambers is a driving wheel on bass, and atop it all was the black cherry tartness of muted Miles. There are thousands of other versions of "Summertime" and most of them are just that: other versions. Miles' is the reference for what a hip "Summertime" should sound like.

Next up are two shots from the first great quintet and two transitional pieces. Miles’ “Surrey With The Fringe On Top” and “If I Were A Bell,” are quintessential examples of what black cool jazz sounded like. Medium tempo, deep swing with that hint of danger Coltrane’s sound injected. Think: a jazz club in what used to be called the ghetto. Deep night, one or two in the autumn morning. All the squares are gone and anyone hanging is making the scene, which means they dig the music and dig doing whatever the music might suggest or inspire.

One thing not often mentioned was the intellectual complexity: this was music you felt, nodded your head to, but also music that provoked thought. It called for concentration and deep, existential conversations about the meaning of one’s life. Not just how one felt but more importantly what one thought about feeling the way we felt when we listened. This music made it hip to be intelligent. Some poetry, or more likely, a book (or even a chess match) was never too far away from this music.

We open with two Miles and Gil Evans tracks. This is the caviar of cool jazz, they might as well have even put instructions for how to make a dry martini on the back cover of Miles Ahead. And, of course, that hip, hip, swinging version of "Summertime." Philly Joe’s rim shots are down in the mix but no problem because Paul Chambers is a driving wheel on bass, and atop it all was the black cherry tartness of muted Miles. There are thousands of other versions of "Summertime" and most of them are just that: other versions. Miles' is the reference for what a hip "Summertime" should sound like.

Next up are two shots from the first great quintet and two transitional pieces. Miles’ “Surrey With The Fringe On Top” and “If I Were A Bell,” are quintessential examples of what black cool jazz sounded like. Medium tempo, deep swing with that hint of danger Coltrane’s sound injected. Think: a jazz club in what used to be called the ghetto. Deep night, one or two in the autumn morning. All the squares are gone and anyone hanging is making the scene, which means they dig the music and dig doing whatever the music might suggest or inspire.

One thing not often mentioned was the intellectual complexity: this was music you felt, nodded your head to, but also music that provoked thought. It called for concentration and deep, existential conversations about the meaning of one’s life. Not just how one felt but more importantly what one thought about feeling the way we felt when we listened. This music made it hip to be intelligent. Some poetry, or more likely, a book (or even a chess match) was never too far away from this music.

We devotees of being-in-the-know used to do listening parties. Gather, a few jiggers of whiskey or a jug of wine and Miles, and it was on. There was, of course, much to be discussed because by the sixties the Civil Rights movement was in full effect and Miles was seen as both elegantly cool and fiercely militant. Getting beat-up by the cops in front of a New York nightclub where he was the featured artist actually elevated Miles’ reputation. Yeah he got his ass whipped but he didn’t back down, turn Tom, and sheeplishly vacate the sidewalk because some racist cop told him to move on. We knew all those stories and we heard all those stories in the music, especially the way Miles and company recast the tin pan alley and show tunes of that era.

Then Trane split and Miles was adrift for a minute. You can hear it in “Someday My Prince Will Come.” Right off the bat there is a bass line announcing a new direction. And, my god, this was a Walt Disney tune. Red Garland’s famous block chords are gone. Wynton Kelly is doing a Bud Powell influenced albeit blues drenched, single note style of piano that is appropriate for the hotter sound Miles was headed toward. Miles talked Trane into returning to take a solo, and what a solo!

Pay close attention to the bass. It’s a marvel of minimalism. Here we have a Miles trademark: take a song that is sappy or schmaltzy at best and turn that banality into something elegant and beautiful, in waltz time no less. Hank Mobley takes the first sax solo. He’s the guy who was called in to replace Trane. Mobley has been dubbed the middle-weight champ to indicate that he is damn good but he’s not in the same weight class with Coltrane. So when Trane enters, it’s all over because we know the music is going someplace else.

We devotees of being-in-the-know used to do listening parties. Gather, a few jiggers of whiskey or a jug of wine and Miles, and it was on. There was, of course, much to be discussed because by the sixties the Civil Rights movement was in full effect and Miles was seen as both elegantly cool and fiercely militant. Getting beat-up by the cops in front of a New York nightclub where he was the featured artist actually elevated Miles’ reputation. Yeah he got his ass whipped but he didn’t back down, turn Tom, and sheeplishly vacate the sidewalk because some racist cop told him to move on. We knew all those stories and we heard all those stories in the music, especially the way Miles and company recast the tin pan alley and show tunes of that era.

Then Trane split and Miles was adrift for a minute. You can hear it in “Someday My Prince Will Come.” Right off the bat there is a bass line announcing a new direction. And, my god, this was a Walt Disney tune. Red Garland’s famous block chords are gone. Wynton Kelly is doing a Bud Powell influenced albeit blues drenched, single note style of piano that is appropriate for the hotter sound Miles was headed toward. Miles talked Trane into returning to take a solo, and what a solo!

Pay close attention to the bass. It’s a marvel of minimalism. Here we have a Miles trademark: take a song that is sappy or schmaltzy at best and turn that banality into something elegant and beautiful, in waltz time no less. Hank Mobley takes the first sax solo. He’s the guy who was called in to replace Trane. Mobley has been dubbed the middle-weight champ to indicate that he is damn good but he’s not in the same weight class with Coltrane. So when Trane enters, it’s all over because we know the music is going someplace else.

At first that someplace else was backward to cooler times, which “On Green Dolphin Street” indicates. This musical retrenchment was “cool” but the events happening during that time period demanded a different temperature. I believe Trane had already lit the fire and, once burned, Miles yearned for more of that out-there-ness heat. “Bye Bye Blackbird” is from Trane’s last 1960 European tour with Miles and was recorded at a Paris concert way before “Green Dolphin,” which was recorded in 1961 at The Blackhawk night club in San Francisco. Notice the irony of returning to the cool sound in the city known as beatnik heaven. Compare the Paris recording to the San Francisco record. You can hear how Trane was pushing the band somewhere else—and, yes, not everyone was ready to go. You can hear a large contingent of the French audience booing and an equally vociferous element cheering. It was clearly a bloody birth. Ultimately Miles elected to move ahead rather than stand pat on the cool approach.

The next three cuts (“My Funny Valentine,” “Stella By Starlight,” and “I Thought About You”) are from the new quintet just before Wayne Shorter joins Miles. The tenor saxophonist is George Coleman who, to continue the boxing metaphor, is a light-heavyweight. I love what Coleman does. If you’re going to play that cool style, if you’re going to play standards, if you’re going to swing, well then be cool, play and swing like George. Except, the new direction was not about returning to the old ways even thought initially they used an old repertoire.

This marked the end of the transitional journey to the next great quintet (Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, Tony Williams on drums, and composer Wayne Shorter on tenor replacing George Coleman).

Wayne’s most significant contribution was as a composer. Not only did Shorter bring great tunes to the band, I believe he encouraged the others to compose. Shortly thereafter they completely abandoned doing standards. By then we were into the seventies. Nobody was focusing on old shit. Socially, everybody—well certainly active and intelligent black folk and the progressive wing of what was sometimes then referred to as mother-country liberals—we were all trying to bring the new, trying to be original, trying to come up with something unique. Reflecting that social and political reality, the music changed, radically.

Over a decade later when Miles retrenched to playing standards, it was mostly selecting contemporary pop songs of the time period rather than resurrecting the pre-sixties standards that had previously made up the bulk of Miles recorded work. The long, twenty-minute version of “My Man’s Gone Now” is the exception that proves the rule. Significantly Miles is once again on a relaxed tip and once (or is this thrice? it's sometimes hard to keep track of Miles without a scorecard) again you hear Miles’ mastery of playing a ballad.

At first that someplace else was backward to cooler times, which “On Green Dolphin Street” indicates. This musical retrenchment was “cool” but the events happening during that time period demanded a different temperature. I believe Trane had already lit the fire and, once burned, Miles yearned for more of that out-there-ness heat. “Bye Bye Blackbird” is from Trane’s last 1960 European tour with Miles and was recorded at a Paris concert way before “Green Dolphin,” which was recorded in 1961 at The Blackhawk night club in San Francisco. Notice the irony of returning to the cool sound in the city known as beatnik heaven. Compare the Paris recording to the San Francisco record. You can hear how Trane was pushing the band somewhere else—and, yes, not everyone was ready to go. You can hear a large contingent of the French audience booing and an equally vociferous element cheering. It was clearly a bloody birth. Ultimately Miles elected to move ahead rather than stand pat on the cool approach.

The next three cuts (“My Funny Valentine,” “Stella By Starlight,” and “I Thought About You”) are from the new quintet just before Wayne Shorter joins Miles. The tenor saxophonist is George Coleman who, to continue the boxing metaphor, is a light-heavyweight. I love what Coleman does. If you’re going to play that cool style, if you’re going to play standards, if you’re going to swing, well then be cool, play and swing like George. Except, the new direction was not about returning to the old ways even thought initially they used an old repertoire.

This marked the end of the transitional journey to the next great quintet (Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, Tony Williams on drums, and composer Wayne Shorter on tenor replacing George Coleman).

Wayne’s most significant contribution was as a composer. Not only did Shorter bring great tunes to the band, I believe he encouraged the others to compose. Shortly thereafter they completely abandoned doing standards. By then we were into the seventies. Nobody was focusing on old shit. Socially, everybody—well certainly active and intelligent black folk and the progressive wing of what was sometimes then referred to as mother-country liberals—we were all trying to bring the new, trying to be original, trying to come up with something unique. Reflecting that social and political reality, the music changed, radically.

Over a decade later when Miles retrenched to playing standards, it was mostly selecting contemporary pop songs of the time period rather than resurrecting the pre-sixties standards that had previously made up the bulk of Miles recorded work. The long, twenty-minute version of “My Man’s Gone Now” is the exception that proves the rule. Significantly Miles is once again on a relaxed tip and once (or is this thrice? it's sometimes hard to keep track of Miles without a scorecard) again you hear Miles’ mastery of playing a ballad.

No other post-bop jazz musician had been both so assertive and so influential in playing ballads. A bunch of cats still played cool but they didn’t capture the attention of young lions looking to make new music. Miles had the charisma that most of his cool contemporaries lacked. Once you heard what Miles did with standards, well, a new standard was set.

I believe that one of the hippest ways of being cool was to take something square, flip it, and present the old song in a new way. Of course, Miles’ trademark was minimalism but in order for that minimalism to fully work its magic, Miles needed some fire in the hole, which in his last years was provided by saxophonist Kenny Garrett fulfilling the role of Coltrane. Garrett was the perfect foil for the older Miles Davis. Garrett on “Human Nature” is like Trane on “Blackbird.”

Over in the covers section we will hear a vocal and an instrumental version of each of the standards that Miles delivers here in the classic section. More on that when you get there.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Miles Plays Standards Playlist

No other post-bop jazz musician had been both so assertive and so influential in playing ballads. A bunch of cats still played cool but they didn’t capture the attention of young lions looking to make new music. Miles had the charisma that most of his cool contemporaries lacked. Once you heard what Miles did with standards, well, a new standard was set.

I believe that one of the hippest ways of being cool was to take something square, flip it, and present the old song in a new way. Of course, Miles’ trademark was minimalism but in order for that minimalism to fully work its magic, Miles needed some fire in the hole, which in his last years was provided by saxophonist Kenny Garrett fulfilling the role of Coltrane. Garrett was the perfect foil for the older Miles Davis. Garrett on “Human Nature” is like Trane on “Blackbird.”

Over in the covers section we will hear a vocal and an instrumental version of each of the standards that Miles delivers here in the classic section. More on that when you get there.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Miles Plays Standards Playlist

01 “My Ship” - Miles Ahead

01 “My Ship” - Miles Ahead

02 “Summertime” - Porgy & Bess

02 “Summertime” - Porgy & Bess

03 “Surrey With The Fringe On Top” - Chronicle: The Complete Prestige Recordings

04 “If I Were A Bell”

03 “Surrey With The Fringe On Top” - Chronicle: The Complete Prestige Recordings

04 “If I Were A Bell”

05 “Someday My Prince Will Come” - Someday My Prince Will Come

05 “Someday My Prince Will Come” - Someday My Prince Will Come

06 “On Green Dolphin Street” - In Person Saturday Night At The Blackhawk

06 “On Green Dolphin Street” - In Person Saturday Night At The Blackhawk

07 “Bye Bye Blackbird” - Olympia 1960

07 “Bye Bye Blackbird” - Olympia 1960

08 “My Funny Valentine” - The Complete Concert 1964 My Funny Valentine

09 “Stella By Starlight”

10 “I Thought About You”

08 “My Funny Valentine” - The Complete Concert 1964 My Funny Valentine

09 “Stella By Starlight”

10 “I Thought About You”

11 “Time After Time” - Live Around the World

11 “Time After Time” - Live Around the World

12 “My Man's Gone Now” - We Want Miles

12 “My Man's Gone Now” - We Want Miles

13 “Human Nature” - Live Around the World

13 “Human Nature” - Live Around the World

This entry was posted on Tuesday, November 16th, 2010 at 9:38 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

One Response to “MILES DAVIS / “Miles Plays Standards””

November 21st, 2010 at 2:47 am

Another fantastic breath of life week. The Miles posts are brilliant — always so good to get the context while listening to the development.

Great to hear the Kiwi sounds too.

Thanks so much Kalamu!

Leave a Reply

| top |