VARIOUS ARTISTS / “African Beats Mixtape”

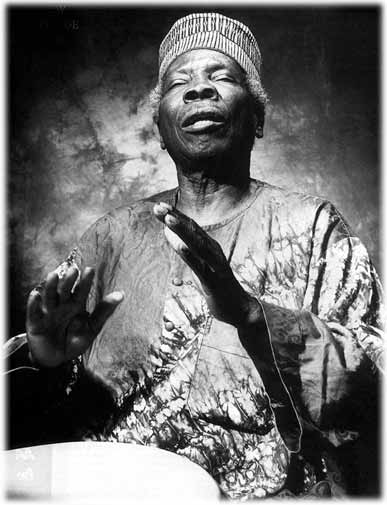

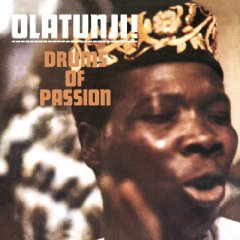

I was in sixth grade when Drums Of Passion by Babatunde Olatunji was released in 1958. I didn’t catch up to it until some to or three years later but even then it was still news. Some more years later, Carlos Santana had a big hit covering “Jingo.” By the late sixties we all knew who Olatunji was and that includes John Coltrane.

Turns out that Trane and Tunji were hooking up to work together—Trane’s last commercially released concert recording was at Olatunji Center of African Culture in Harlem. Years before that Trane recorded the composition “Tunji.” So yes, being a Trane freak, I had to know Olatunji.

Babatunde Olatunji had journeyed to the USA to study medicine and ended up establishing himself as the preeminent states-based, African musician. He heavily promoted African culture, mainly but not exclusively Nigerian music and dance.

Drums Of Passion is one of those early landmark albums that was the beginning of a trend before any movement was in sight or earshot. Jazz musicians knew—hell, the best of them are always in the know; being in the know is essential to how they get to be the best—but the general public lagged far behind. Drums Of Passion offered some of us the opportunity to catch up a little bit.

There is not much more necessary to say except listen to the rhythms, to the rhythms. Listen. To the rhythms.

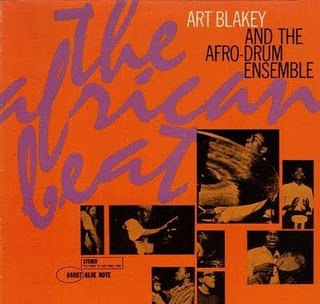

By the mid-sixties I was listening heavy to Art Blakey. I dug Max Roach’s melodic treatments and eventually signed onto the Tony Williams-forever bandwagon—although, to be clear, Williams was but a younger and truly innovative extension of Blakey’s approach. And, of course, there was Elvin Jones.

I could copy some of Art Blakey’s solos on drums (once even won a talent show contest at Fort Bliss, Texas playing a drum solo patterned on Blakey) and I could even dream of playing like Tony, but Elvin was way, way beyond not only what I could do but also far beyond what I could even imagine myself doing.

So anyway, I had a ton of Blakey records (and believe me that’s possible given the goo-gobs of releases Blakey piloted). One of Blakey’s albums that I always ended up returning to was The African Beat.

Art led a literal battery of percussionist, including regular trombonist Curtis Fuller featured exclusively on tympani. There was no piano, no bass and the only horn was Yusef Lateef doing his “exotic” thing mixed with his funky tenor thing. I never tried to play any of Art’s solos from that record because they were so much a part of the ensemble of drummers.

This album illustrates a jazz approach to African rhythms, i.e. soloists stand out from the ensemble with more emphasis on the soloist than on the ensemble, or more precisely I should say, with the solo statements being a major part of the overall ensemble.

One of the major compositions, “Love, The Mystery Of,” remains a favorite of mine. In 1994 while attending Panafest in Ghana, West Africa I had the opportunity to meet the song’s composer Guy Warren. Warren had been featured in Haile Gerima’s famous movie Sankofa. I hung out with Gerima and one day we took a day trip into the countryside to meet Warren. The music was always and always will be central to my existence, so you can imagine how important visiting Warren in his home was to me.

I listened to Blakey’s The African Beat more than I did to Drums Of Passion.

I was standing in the wings waiting for the conclusion of the encore number. My sista-friend and concert producer Baraka Sele had asked me to do a public interview of the musicians at the conclusion of the concert. I was happy to oblige and damn the music was happening. We were at NJPAC (New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Newark, New Jersey) where Ms. Sele is assistant vice-president of programming.

Saxophonist David Murray working with Doudou Rose’s drummers. On organ Donald Smith, the talented brother of Lonnie Liston Smith, was tearing it up. Donald and I knew each other from back when he was in an Illinois college band that played at the jazz festival in New Orleans and all the hip young musicians would hang out the whole weekend at Willie Tee and Earl Turbinton’s Jazz Workshop in the French Quarter.

Donald waved at me, I smiled back, patting my foot and shaking my leg. But then the music just kept getting more and more gooder (I know it’s ungrammatical but that approximates how good the music was getting when it already was real good). At first faintly, and then insistently, the music was calling my name, especially those damn drums. I started doing a little one drop step.

I was still backstage in the wings. Donald was smiling harder, bobbing his head. Some of the musicians on stage saw me dancing and a couple of the drummers waved to me to come and dance. I hung back, or I should say, tried to hang back but the music had lassoed my butt and was pulling me inch by inch toward those powerful drums. I guess it was about a half hour later before the music stopped and we were all sitting in chairs across the front of the stage. I was in the center, right near where I was when the music part of the program finally ended.

Master Doudou Rose speaking through an interpreter thanked those of us who had danced. He said the music was made for dancing. To which all I could do was say “amen.”

That was not my first exposure to Doudou. Somehow I had gotten hold of his album Djabote, which was recorded on Goree Island in Senegal, West Africa and featured 50 drummers and 80 singers—the drummers were mainly Muslims, the singers were mainly Catholic. The music was all African.

Djabote is in a category of one. I have been to numerous drumming sessions on three continents and a bunch of Caribbean islands including Haiti and Cuba. I owned a lot of drum recordings. There is nothing else remotely like what Doudou does.

The power of it, the intricacy of the interlocking rhythms, the unity of fifty drummers all hitting on the one, the voices floating above and interweaving between the beats; the compositional shape of the rhythm patters; all of that and more of that—this was drum heaven.

Djabote is not a blowing session where drummers wild out. This is an orchestrated concert with music passionately conducted by Doudou Ndiaye Rose, the widely acknowledge Senegalese master of percussion. This is one of the most spiritual recordings ever made.

Drums are the earth-based, human heartbeat of life. Drums of Passion, The African Beat and Djabote are three major indexes in the history of recorded African beats.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

African Beats Mixtape Playlist

The first three tracks are from Drums Of Passion by Babatunde Olatunji

01 “Akiwowo (Ah-Key-Woh-Woh)”

02 “Baba Jinde (Baba-Gee-Un-Day)”

03 “Jin-Go-Lo-Ba (Jin-Go-Low-Bah)”

The next three tracks are from The African Beat by Art Blakey

04 “Love, The Mystery Of”

05 “Ayiko, Ayiko (Welcome, Welcome)”

06 “Ero Ti Nr'Ojeje”

The remaining six tracks are from Djabote by Doudou N’Diaye Rose

07 “Sidati Aidara”

08 “Chants Du Burgam”

09 “Baye Kene Ndiaye”

10 “Tabala Ganar”

11 “Diame”

12 “Walo”

This entry was posted on Monday, February 1st, 2010 at 4:02 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

2 Responses to “VARIOUS ARTISTS / “African Beats Mixtape””

August 22nd, 2010 at 1:49 am

HI there,

Thanks for sharing it blog over here… amazingly written

Thanks,

kate

January 11th, 2015 at 9:23 pm

I was fortunate to land on your article and ut made me feel very good. It shows how much Africans have contributed to the world music.

Thank you very much for sharing.

Leave a Reply

| top |