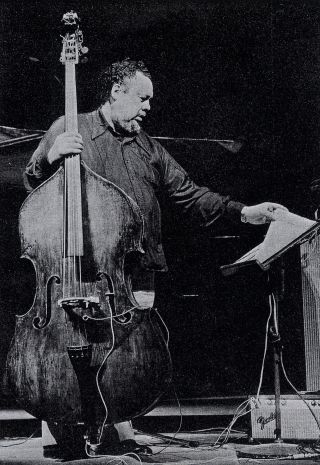

CHARLES MINGUS / “Trio And Group Dancers”

I graduated from high school in May 1964. From August 1964 through March 1965 I attended Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota—I stayed that long because I had to wait for the weather to break in order to make my getaway. It was cold. Totally cold.

Years later I began to appreciate the learning experience of being at Carleton, the people I met, the films I saw, lectures I absorbed, the completely new to me variety of classmates. I remember one senior student who was dating a guy that was present when Malcolm X was gunned down. Some years later I got to know Robert Allen, a man I first met through reading his letter he wrote to the senior student describing the horror.

While there I had been dating a fellow student from Turkey. To a 17-year-old freshman from the deep south, Carleton was a totally different world that introduced me to the wider world, and started me on some roads I would continue to travel for years. For example, my first gig as a jazz DJ was at the Carleton college radio station—Sunday nights, 8pm to 10pm. I played a wide variety of jazz, emulating Larry McKinley, the famous New Orleans WYLD radio personality who had a Satuday afternoon program called This Is Jazz.

One of my most daring shows was playing the entire Black Saint And The Sinner Lady album. The whole thing. No chatter, not even when I flipped the record over so quickly and smoothly there was hardly an appreciable pause.

Preparing to do the write up for this week’s BoL, I started listening to Black Saint trying to decide what section to feature or whether I was going to just do one or maybe two tracks, or whatever… you know just feeling it out. I started with the longest cut, the fourth song, which was actually a medley of the last three parts of the suite.

As I listen I almost cried. I certainly hollered loudly during certain parts.

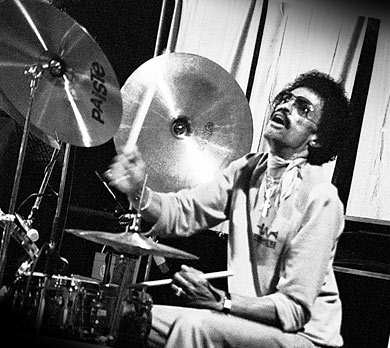

For a year or so circa 1967/68 I was a part-time professional drummer. I had first been highly influenced by Art Blakey and then totally blown away by Tony Williams. But the discipline and beauty of Max Roach was also deeply embedded in my ear. And yet, beyond all of the above mentioned (and also beyond the incomparable, pile-driving magician Elvin Jones), beyond every drummer I knew and respected there was the whirlwind that was Danny Richmond, Mingus’ main drummer.

Preparing to do the write up for this week’s BoL, I started listening to Black Saint trying to decide what section to feature or whether I was going to just do one or maybe two tracks, or whatever… you know just feeling it out. I started with the longest cut, the fourth song, which was actually a medley of the last three parts of the suite.

As I listen I almost cried. I certainly hollered loudly during certain parts.

For a year or so circa 1967/68 I was a part-time professional drummer. I had first been highly influenced by Art Blakey and then totally blown away by Tony Williams. But the discipline and beauty of Max Roach was also deeply embedded in my ear. And yet, beyond all of the above mentioned (and also beyond the incomparable, pile-driving magician Elvin Jones), beyond every drummer I knew and respected there was the whirlwind that was Danny Richmond, Mingus’ main drummer.

If you have never played modern jazz as a drummer you probably do not realize how difficult it is to play free, to improvise and at the same time hold together the ensemble’s rhythmic pulse. I know that a lot of jazz drumming sounds like a mad hatter pounding to no purpose other than loud noise but even doing that is difficult in the midst of music as wide open as this work.

The diminuendos and crescendos are nothing short of impossible to match in both their emotional impact and the precision of their execution. At certain moments you don’t have time to decide what to play, you just have to play counting on your instinct and gut. You don’t choose to hit this cymbal or rim shot the snare—you do whatever you do and keep moving.

In the Black Saint context, Danny Richmond was the tail who had to lead the tiger. By that I mean, they were playing a composition full of shifting rhythm patterns and wild swings in the dynamics. In one sense he knew where they were going but he never could be sure when they would get there. Nevertheless, Richmond had to be the engine keeping the music moving. He both augmented what the men were playing by providing appropriate stokes, rolls and cymbal crashes in sync with whatever they came up with while at the same time he pulled the whole ensemble into and out of the various stops and starts—doing it on time, on the dime, no hesitation.

If you have never played modern jazz as a drummer you probably do not realize how difficult it is to play free, to improvise and at the same time hold together the ensemble’s rhythmic pulse. I know that a lot of jazz drumming sounds like a mad hatter pounding to no purpose other than loud noise but even doing that is difficult in the midst of music as wide open as this work.

The diminuendos and crescendos are nothing short of impossible to match in both their emotional impact and the precision of their execution. At certain moments you don’t have time to decide what to play, you just have to play counting on your instinct and gut. You don’t choose to hit this cymbal or rim shot the snare—you do whatever you do and keep moving.

In the Black Saint context, Danny Richmond was the tail who had to lead the tiger. By that I mean, they were playing a composition full of shifting rhythm patterns and wild swings in the dynamics. In one sense he knew where they were going but he never could be sure when they would get there. Nevertheless, Richmond had to be the engine keeping the music moving. He both augmented what the men were playing by providing appropriate stokes, rolls and cymbal crashes in sync with whatever they came up with while at the same time he pulled the whole ensemble into and out of the various stops and starts—doing it on time, on the dime, no hesitation.

Dannie Richmond. I’m telling you the man is the real Captain Marvel. He deserves a medal of honor for keeping time on this one.

To illustrate what I mean, listen to any of the tracks twice, or thrice, and on the fourth time see if you can even pat your foot in time all the way through without getting flustered and wrong-footed.

Besides the “holy shit Dannie, you a bad man” on the skins, besides the deeptitude of Charles Mingus’ composition—and that is a lot of besides to put aside, but anyway, besides all of the aforementioned, notice the fierceness of this music.

Mingus got these musicians to play at a level of intensity any of them rarely, if ever, matched on any other record they made. Shortly, Trane was to arrive along with Albert Ayler, and they brought Einsteinium nuclear fission-esque saxophone energy to modern jazz—oh, and must mention Pharoah Sanders in that number—but what they brought was mostly improvisation. What Mingus drops here is both composition and improvisation. Not even Sun Ra has a record that is as exhaustive as this work.

Finally (or should I say, for now this is all I have to say), it is stunningly clear that The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady captures the thoroughgoing emotional intensity of magnificent fucking better than any other record ever made.

The record is so graphic it’s almost pornographic. It’s the energy of sex that Mingus captures. There’s no cooing and oohing, no squealing and moaning, just eleven men making music like somebody had a gun to their heads and prompted them to play hard or die. Nobody died that day.

When the radio show ended at ten, I was exhausted. I didn’t smoke then and don’t now but that was one time I could have used a cigarette.

Dannie Richmond. I’m telling you the man is the real Captain Marvel. He deserves a medal of honor for keeping time on this one.

To illustrate what I mean, listen to any of the tracks twice, or thrice, and on the fourth time see if you can even pat your foot in time all the way through without getting flustered and wrong-footed.

Besides the “holy shit Dannie, you a bad man” on the skins, besides the deeptitude of Charles Mingus’ composition—and that is a lot of besides to put aside, but anyway, besides all of the aforementioned, notice the fierceness of this music.

Mingus got these musicians to play at a level of intensity any of them rarely, if ever, matched on any other record they made. Shortly, Trane was to arrive along with Albert Ayler, and they brought Einsteinium nuclear fission-esque saxophone energy to modern jazz—oh, and must mention Pharoah Sanders in that number—but what they brought was mostly improvisation. What Mingus drops here is both composition and improvisation. Not even Sun Ra has a record that is as exhaustive as this work.

Finally (or should I say, for now this is all I have to say), it is stunningly clear that The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady captures the thoroughgoing emotional intensity of magnificent fucking better than any other record ever made.

The record is so graphic it’s almost pornographic. It’s the energy of sex that Mingus captures. There’s no cooing and oohing, no squealing and moaning, just eleven men making music like somebody had a gun to their heads and prompted them to play hard or die. Nobody died that day.

When the radio show ended at ten, I was exhausted. I didn’t smoke then and don’t now but that was one time I could have used a cigarette.

P.S. The feature selection is part 4 and took up the entire second side of the Lp in the vinyl format when first issued. However, the track was actually a medley. Here’s the breakdown of the tracks as originally issued.

Side one

"Track A — Solo Dancer" – 6:20

Stop! Look! and Listen, Sinner Jim Whitney!

"Track B — Duet Solo Dancers" – 6:25

Hearts' Beat and Shades in Physical Embraces

"Track C — Group Dancers" – 7:00

(Soul Fusion) Freewoman and Oh, This Freedom's Slave Cries

Side two

"Mode D — Trio and Group Dancers"

Stop! Look! and Sing Songs of Revolutions!

"Mode E — Single Solos and Group Dance"

Saint and Sinner Join in Merriment on Battle Front

"Mode F — Group and Solo Dance"

Of Love, Pain, and Passioned Revolt, then Farewell, My Beloved, 'til It's Freedom Day – 17:52

P.P.S. Trivia that makes you go "ummm..."—the original Black Saint And The Sinner Lady liner notes were written by Mingus and Dr. Edmund Pollock, who was Mingus’ psychotherapist.

P.S. The feature selection is part 4 and took up the entire second side of the Lp in the vinyl format when first issued. However, the track was actually a medley. Here’s the breakdown of the tracks as originally issued.

Side one

"Track A — Solo Dancer" – 6:20

Stop! Look! and Listen, Sinner Jim Whitney!

"Track B — Duet Solo Dancers" – 6:25

Hearts' Beat and Shades in Physical Embraces

"Track C — Group Dancers" – 7:00

(Soul Fusion) Freewoman and Oh, This Freedom's Slave Cries

Side two

"Mode D — Trio and Group Dancers"

Stop! Look! and Sing Songs of Revolutions!

"Mode E — Single Solos and Group Dance"

Saint and Sinner Join in Merriment on Battle Front

"Mode F — Group and Solo Dance"

Of Love, Pain, and Passioned Revolt, then Farewell, My Beloved, 'til It's Freedom Day – 17:52

P.P.S. Trivia that makes you go "ummm..."—the original Black Saint And The Sinner Lady liner notes were written by Mingus and Dr. Edmund Pollock, who was Mingus’ psychotherapist.

This entry was posted on Monday, June 1st, 2009 at 7:47 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

One Response to “CHARLES MINGUS / “Trio And Group Dancers””

June 5th, 2009 at 2:44 pm

Having liner notes written in concert with your psychotherapist makes me go hmmm, indeed. The guitar in these pieces keeps surprising me. It is beautiful and lyrical and a wonderful complement to and respite from the type of intensity on display in the more horn-centric bits of the piece.

The cuts in the jukebox are quite beautiful. Great music to write to.

Kiini

Leave a Reply

| top |