VARIOUS ARTISTS / “Harold Battiste Mixtape”

Harold Battiste: a history of our future. That which is eaten changes the one who eats. You may never have heard of him by name but you have heard his music. There is no American music as a major contribution to world culture, none, without the seminal and essential contributions of black musicians.

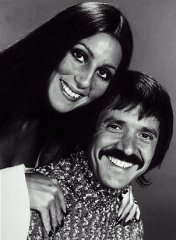

Harold Battiste was born in 1931 in New Orleans, Louisiana. In addition to founding All For One (AFO) Records, America’s first collectively musician-owned, black record company, Harold Battiste was in the vanguard of musical directors on television with his pioneering work with the Sonny & Cher nationally broadcast television show. Harold also was an arranger and in-studio producer for Sam Cooke and co-creator of the infamous Dr. John musical persona. A retired professor of music, at 78 years old, Harold Battiste continues to work with and inspire young musicians in New Orleans.

On Saturday, March 21, 2009 Harold was honored with a concert featuring the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and a plethora of guest musicians. Generally these tribute events too often are musically lame, nostalgia trips, especially when the music is presented with a classical orchestra. The cloak of classical music is supposed to somehow supply an element of elegance and class, usually it’s really nothing more than the death shroud of cooption.

Despite my inherent anti-establishment bias, I recognized something deeper going down in Dixon Hall on the campus of Tulane University, a deeptitude that grounded the music and made for an authentically enjoyable night.

The concert was produced by trumpeter Edward Anderson. Anderson studied under Harold Battiste at the University of New Orleans. Edward Anderson is currently Director of the Institute of Jazz Culture and Assistant Professor of Music at Harold’s alma mater, Dillard University.

I sat next to the honoree for the event. There was genuine warmth in the greetings and felicitations of a stream of well-wishers and admirers who briefly visited with Harold, shaking his hand and exchanging words of praise and gratitude.

The musicians played well, there were even a couple of extraordinary moments: Henry Butler playing some amazing solo piano; Wanda Rouzan camping it up singing Sonny & Cher songs but also genuinely singing; Bill Summers on congas and percussion and Alexei Marti on timbales providing a deft rhythm bed for an expanded arrangement by Edward Anderson and Kyle Saulnier of Harold’s composition “Marzique Dancing.” I was told that the night’s proceedings were recorded for future broadcast on public radio; hopefully, that is in fact the case.

I am currently negotiating to produce a Harold Battiste tribute CD. The music on this mixtape is the preliminary line-up for a CD whose working title is: Harold Battiste – The Man Behind The Music.

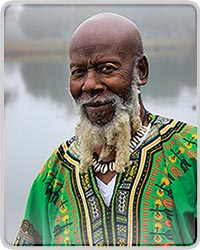

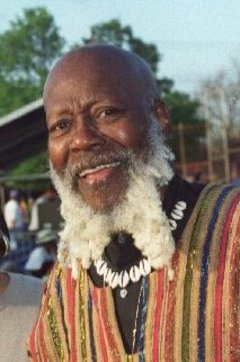

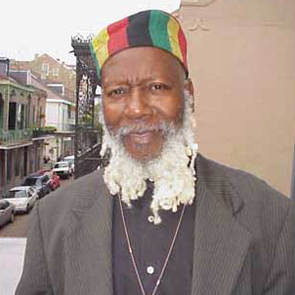

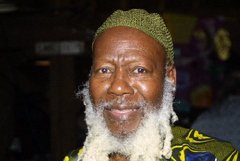

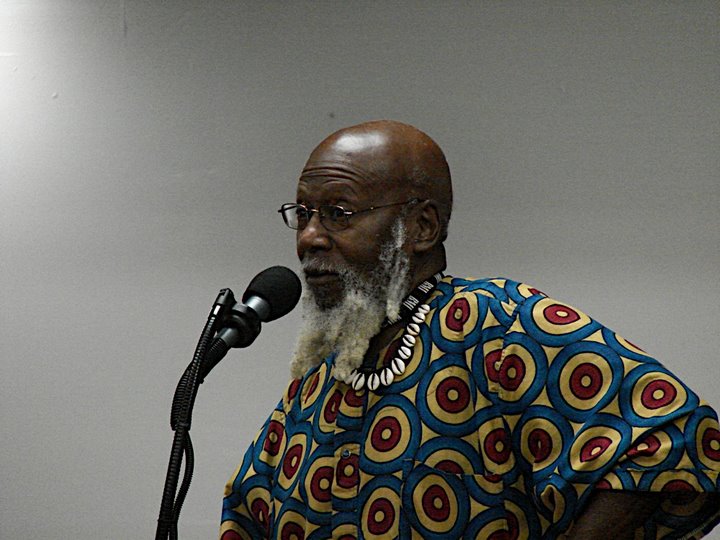

Harold and I are close friends—as one of the many well-wishers noted, “yall look like brothers.” We both had on African attire and both had grey beards. Wednesdays are our weekly date to dine together. We often speak about what I shall call ‘the disappearance of blackness,’ i.e. the transformation of our people and our contributions into something whose representation is often at odds with its reality.

The main concern is not the transformation itself but rather the representation: we are erased from history; others are given credit for “discovery” and lauded as “creators”; the pubic is fed fowl and told that the music is fish. It upsets Harold. I tell him, vexation and worriation are capitalism’s inevitable trademark.

One small vexation example will suffice to illustrate how frustrating and pervasive the little things can be. The program handout and articles about the Harold Battiste tribute program in the daily paper all identify Harold as a graduate of Booker T. Washington High School. Harold graduated from Gilbert Academy, which closed in the late fifties. What’s happening is that the error has not only developed a life of it’s own but worse, since the Times Picayune is the newspaper of record that researchers use, that error will probably be multiplied many times over.

So what’s the big deal about Harold’s high school? This illustrates how our true history gets erased and over time replaced by an alternate version. The process is not necessarily a conspiracy or malicious but regardless of intent the result is a distorted version of our reality. We’ve got tons of work to do.

Back in the mid-eighties after visiting Haiti, I wrote a poem that included the lines: when you swim with sharks, be careful less you become the diner. In that regard, no contemporary ocean is more treacherous that the American entertainment industry.

What are we to do? When we go along to get along, our contributions get subsumed into the dominant culture and we are, as they used to say in Argentina, “disappeared.” If we fight for recognition, our friends ask why are we emphasizing race, don’t we want to eliminate an emphasis on color; while our foes accuse us of reverse racism.

I think the only solution is to tell the truth: the truth about our struggles, the truth about our contradictions and confusions, the truth about our conundrums standing at the cross-roads of modernity and tradition, unsure of how to proceed. But time no stand still. Proceed we must, proceed or die out completely.

At the conclusion of the tribute program, Harold mounted the stage and spoke a few parting words. Poignantly he spoke about all of his colleagues and compatriots who have already gone on to glory. He spoke about his anger at clarinetist and music educator Alvin Batiste, who died last year. “I was angry because he died and left me here.”

Reeling off a quick list of recently deceased friends and musical cohorts, Harold avowed that he never expected to live as long as he has. “I wondered why I was still here. I guess, maybe, it was to get to see this night.”

And then we chuckled inwardly and smiled the bittersweet smile of survivors recognizing both the blessing and the curse of surviving the long march through the slaughter.

What slaughter, you may ask. Ah, my friend, look back over the path we have trod. Those sign posts and roadside mile markers are the bones painted with the blood of those of us who did not make it to where we are today. Life is a business littered with death, and in America, for many of us (generally those of us who are of color, and especially those of us who are also poor), both our life and our death are generally ignored even as it is we who have given life to this intensely contradictory social experiment popularly known as the United States of America.

What America would be if it were not for we, is a reality too terrible to contemplate. All men are created… who are the true creators and at what cost their creations?—these are the questions we should ask and answer. All of the creators and the contexts within which they created should be both critiqued and acknowledged. There is still so much work to do. To be continued…

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Check the Harold Battiste Mixtape playlist.

1. “She Put the Hurt on Me” - Prince La La - Crescent City Soul

2. “Cry, Cry, Cry” - Alvin Robinson - Gumbo Stew

3. “I Got A Feelin' ” - Nooky Boy - Gumbo Stew

4. “Cha Dooky Doo” - Art Neville – Art Neville

5. “I Know” - Barbara George - I Know

6. “You Talk Too Much” – Joe Jones - The Best Of Joe Jones

7. “Check Mr Popeye” - Eddie Bo - Gumbo Stew

8. “Ya Ya” – Lee Dorsey - More Gumbo Stew

The first eight tracks are all from the second wave of New Orleans R&B, the era that immediately preceded the more famous and more popular Allen Toussaint era. Included are Art Neville, a foundational member of the legendary Neville Brothers; Barbara George, whose hit song exemplifies the spirit of New Orleans R&B—especially when you consider the Melvin Lastie trumpet solo that became a sine qua non essential to the repertoire of any and all New Orleans trumpeters; Joe Jones, one of the early legendary characters of New Orleans R&B with a song whose title passed into popular parlance when confronted with loquacity; Eddie Bo, who died literally the day before Harold tribute concert—Bo will be remembered as the main orchestrator behind the numerous hits, semi-hits and imitation hits for the fifties New Orleans dance craze known as “the Popeye”; and Lee Dorsey whose most famous song is often mis-credited to Allen Toussaint but is actually the result of Harold Battiste’s production work.

Once when I was interviewing Harold many years ago, the whole tale slowly unfolded about “I Know,” Barbara George’s monster hit. Among the numerous revealing truths is that Melvin’s solo was not a solo. Harold had composed the trumpet part and assigned it to Melvin to play at the recording session. I and literally tens of thousands of other New Orleanians grew up with that trumpet sound forever anchored in our ear. So, over forty years after it had sold millions, imagine my surprise to find out that the famous phrases rather than a spontaneous outpouring were actually the meticulous craft of a master working behind the scenes.

9. “The Beat Goes On” – Sonny & Cher - The Essentials Sonny & Cher

The Sonny & Cher story has been told so often and so many different ways. Even though all the anecdotal tales have become more musical myth than factual truth, Harold is central in all of these stories—especially the ones that neglect to mention Harold by name. Thrust into the do-or-die position of musical director for a weekly network broadcast, Harold Battiste was among the first black musicians to fill that position. The irony is that while the music played on television is mainly derived (some would say stolen) from black music, very, very few of the musical directors on network television have been black musicians. On his second go round, Sonny had to literally beg Harold because Harold had by then seen and heard what Hollywood had to offer and it was not to Harold taste. Trivia note: after doing one movie score, Paramount offered to hire Harold to score movies but Harold declined, partly because my man really wanted to be a jazz musician and really enjoyed playing music more than scoring music. There were other considerations, more complex, some of which were not about the music per se but all of which bespoke the difficulties of being yourself in a profession and a social milieu dominated by others. Ah, but regardless of what we do, or don’t do, “the beat goes on.”

10. “Iko Iko” - Dr. John - Dr. John's Gumbo

I’m going to make this simple. Harold was the midwife at the birth of Dr. John. The child would have been stillborn had not Harold been producing, especially in terms of selecting the accompanying musicians and establishing the musical details. Proof of this is that after the second Dr. John recording failed to live up to the first, Atlantic records begged and cajoled until Harold relented to produce Mac Rabbenack’s third album, the one that cemented the reputation of the good Doctor.

Of both Sonny & Cher and Dr. John, Harold takes a philosophical view and softly notes in conversation that back then, one did not get much credit as a producer and arranger, in fact, your name was seldom listed on either musical credits or royalty checks.

11. “You Send Me” – Sam Cooke - Portrait Of A Legend 1951-1964

12. “A Change Is Gonna Come” – Sam Cooke - Portrait Of A Legend 1951-1964

The Sam Cooke relationship is classic. Harold happened to be in the studio when Sam’s initial pop recording session. The idea was to re-make Sam in the Nat King Cole or Johnny Mathis bag. The song was “Summertime” (or some other standard of that type). The recording had gone ok but not exciting. Back room arguments ensued. The behind the scenes big man offered to pay a debt to one his producers by giving the rights of the session to that producer since the guy was insisting that Sam was worth the investment in strings and chorus in the studio. The session producer who was about to make one of the best deals in musical history had been working with Harold who worked for the big man (yeah, yeah, I know all of this would be easier to understand if I just called names but what difference would it make if I said Art Rupe and Bumps Blackwell, without a whole bunch more background, you still wouldn’t understand what went down; anyway…).

So Bumps turns to Harold and asks Harold to do something when Sam tells Bumps that he, Sam, has a song idea. Sam strums so chords on a guitar and repeats an insistent refrain: “you send me.”

Do something, indeed. Harold and Sam worked together. Harold retreated for a spell to contemplate and work. Shortly Harold returns with charts for the singers and flushed out ideas for both the lyrics and the music. They record it as the “B” side of the single. The song catches fire as the results of radio DJs turning the record over and featuring the new song by Sam Cooke.

I would say the rest is history but in this case it would be much more accurate to say the rest is mythology—Harold’s name is not generally called with the cast of characters surround the rise of Sam Cooke are listed. But Sam knew and employed Harold on a long term basis to develop talent and provide in studio assistance.

BTW, on “A Change Is Gonna Come” Harold is playing piano. I said to Harold, man, you’re so far down in the mix, I can’t hear what you’re doing. Harold responded modestly, wel, that’s the way they wanted to mix it at the time. Maybe it does sound better without the piano part, I haven’t heard the raw tapes so I can’t say but I do know, once again, points to the erasure of Harold role in assembling the musicians even though he wasn’t producing this particular session.

Harold is but one of many examples of this particular sinister syndrome.

13. “It’s All Over Now” – The Valentinos – The SAR Story

Here’s another convoluted story that I’m going to simplify for the purposes of this Mixtape listing. The lead singer of The Valentinos vocal group was Bobby Womack. They were friends of Sam Cooke. Cooke had even loaned them the money to buy a car in order to motor out to California after the father of the family put his sons out of their home because he found out the young gospel group had been singing secular music on the side. This was, of course, a predicament that Sam Cooke knew well as he was one of the first major stars of gospel music to cross-over to secular music.

In 1964 this song hit big time, and became even bigger on an international level when The Rolling Stones covered the song and it became their first number one hit. Bobby, as the songwriter, came into a small fortune as a result of royalties. But the twist is that Cooke was killed in 1964 and less than six or so months after Cooke’s death, Bobby Womack married Cooke’s widow. As you might imagine the high drama of the intertwining tales of gossip and fact practically ensured that Harold Battiste's production role gets overlooked.

14. “When The Saints” – Harold Battiste & Ellis Marsalis - Harold Battiste Presents Next Generation

Back in the early fifties when Ellis Marsalis entered college at Dillard University he was playing tenor saxophone in a band called the Groovy Boys (or some other generic nomenclature). Once Ellis hooked up with a senior on campus who was a music major and really advanced, Ellis was persuaded to switch from tenor to piano. The persuader was Harold Battiste. Here, decades later, Harold on soprano and Ellis on piano perform a swinging rendition of a New Orleans standard.

15. “Song For Dance” – Jessie McBride & The Next Generation – Jessie McBride Presents The Next Generation

Houston-born pianist Jessie McBride studied with Harold Battiste at the University of New Orleans, whose jazz program had been established by Ellis Marsalis, who in turn had called for Harold to return home to New Orleans from a nearly three decades long stay in Los Angeles. Harold joined Ellis at UNO and together they taught virtually a whole generation of contemporary jazz musicians. Jessie was so taken with the music and approach of Harold Battiste that he formed a band of younger students to play the historic music and continue the AFO legacy.

“Song For Dance” is a Harold Battiste composition that is available in the Silver Book. Consisting of sheet music, biographies and photographs, The Silver Book represents the jazz oriented life work of Harold Battiste and his AFO cohorts.

This edition of The Next Generation consists of Jesse McBride on piano, David Pulphus on bass, Joe Dyson on drums, Allen Dejan on tenor, Andrew Baham on trumpet, and Rex Gregory on alto.

16. “Body And Soul” – Harold Battiste – unreleased gig tape

17. “Nevermore” – American Jazz Quintet - From Bad To Badder

18. “Cry Again” – Harold Battiste featuring Tammi Lynn – unreleased gig tape

19. “Beautiful Old Ladies” - Harold Battiste – unreleased gig tape

As I said earlier, Harold really wanted to be a full time jazz musician but responsibilities and opportunities for other pursuits often blocked that path while simultaneously opening other roads for Harold to travel. These last four tracks represent Harold in that context.

“Body And Soul” is from a nineties gig at New Orleans’ leading jazz club, Snug Harbor.

“Nevermore” is from a tribute concert/conference series for drummer Ed Blackwell that was produced in Atlanta by Rob Gibson who would go on to become the first director of Jazz at Lincoln Center during Wynton Marsalis tenure. The Blackwell tribute featured the three major bands in which Blackwell was the drummer: The American Jazz Quintet (AJQ), The Ornette Coleman quartet, and Old And New Dreams. At the point of this recording the American Jazz Quintet had not worked together for over 25 years but came together with only one short rehearsal earlier in the day to produce a beautiful tribute concert featuring original members Alvin Batiste on clarinet, Harold Battiste on tenor, Ellis Marsalis on piano, Richard Payne on bass and Edward Blackwell on drums, along with Earl Turbinton on alto subbing for his now deceased mentor, tenor saxophonist Nat Perrilliat, who had in originally taken the tenor chair when Harold relinquished it so that Nat could be featured with the group. Harold figured that Nat was a monster player and that Harold’s hands were already filled composing, arranging and producing for the group.

“Cry Again” is an Ellis Marsalis composition from back in the day and Tammi Lynn was the original AFO featured vocalist. Harold is playing piano on this track.

I believe that “Beautiful Old Ladies,” is Harold’s most notable composition. This version features Harold on saxophone and Ellis Marsalis on piano. Both “Cry Again” and “Beautiful Old Ladies” are from a concert at The Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans.

This entry was posted on Monday, March 23rd, 2009 at 7:02 am and is filed under Contemporary. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |