MILTON NASCIMENTO / “San Vicente”

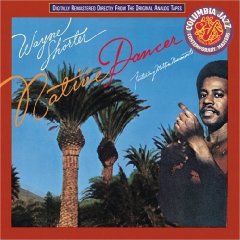

There's something very beautiful that happens with music. It's as if you are walking down the street looking at many different faces, and suddenly you feel strongly they have something in common with you. —Milton NascimentoMilton Nascimento is an absolute glorious monster, a perfect definition of awesome. To know his music is to know the world is smaller than we think but yet the world we create through living is large enough to hold everything, all our creations, all, everything we can do, can think to do, are able to do within the specifics of our circumstances and resources. Milton demonstrates that all of the world can be contained in each of us even though we as individuals are but a small part of the whole. Listening to Milton’s music both humbles me and expands me. Just like many Americans, Milton came to me via Wayne Shorter’s album Native Dancer. The first track, "Ponta De Areia," was pow; sucker punched me. I was looking for Wayne’s next ‘jazz’ album, with Herbie in tow I figured it would be good but, oh, my lord, what was, who was, that voice. I had never heard a man use his falsetto like that, and not just for an effect at climatic moments. It was like Milton was a down-side-up sky diver. He jumped out the plane and instead of floating to earth with an open parachute, he soared upward, and higher, and just zoomed around like gravity wasn’t nothing real. Who was this cat? Recorded September 12, 1974 in Los Angeles, “Ponta de Areia,” and indeed the whole album, is a remarkable synthesis of American jazz and innovative Brazilian music. The band was Wayne Shorter on soprano, Milton on acoustic guitar and vocals, Herbie Hancock on piano, Wagner Tiso on electric piano and organ, Jay Graydon on guitar, Dave McDaniel on bass, Robertinho Silva on drums. The song was composed by Milton Nascimento and his long time collaborator Fernando Rocha Brant. One song told the whole story.

So who was the native dancer of the album’s title? At that time both Wayne (in the band Weather Report) and Herbie (in both his Mwandishi and his Headhunters band) were invested in electronics and fusion. But here was a fusion recording that was acoustic. A real fusion of different worlds rather than merely a fusing of different approaches to the same world.

Native Dancer was not a novelty, in the sense of a unique variation on a well established theme. No, Native Dancer was something completely new. Where bossa nova had fused samba and cool jazz, this was another step toward oneness. Most jazz heads recognized instantly we were in the presence of a miracle.

When I turned over the record cover and saw that this Nascimento man had composed some of the music, needless to say, I knew what my next record purchase was going to be. That was in the mid-seventies, around 1975 or maybe (though I doubt it) as late as ’76—back then I was obsessive about staying current in jazz.

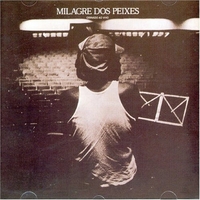

I did not know that Milton had already created a masterpiece with 1972’s Clube de Esquina (which we will deal with later). Nor did I know Milton had a great follow-up with 1973’s Milagre Dos Peixes, and even, for me, supremely impressive live recording with Milagre Dos Peixes: Gravado Ao Vivo, a May of 1974 concert. It’s like digging on Kind of Blue but not knowing Miles Ahead or any of the Prestige ‘Working’ sessions, or better yet, being bowled over by Stevie’s Musiquarium but not knowing Innervisions or Songs In The Key of Life.

Here I was thinking I was on top of what was going down when actually I was way behind the curve, way, way behind. Milton’s debut album had been in 1967, an American version on A&M is available as Milton Nascimento, sometimes as Travessia, not to be confused with the 1969 EMI Odeon release also titled Milton Nascimento, nor confused with the 1999 Brazilian Polygram release O Melhor de Milton Nascimento – Travessia (which, by the way is a good collection for starters but potentially confusing as it presents a number of alternate, rather than original, versions of major compositions).

Unraveling Milton’s discography would confuse Sherlock Holmes. Go here for a quick but no where near complete overview.

So who was the native dancer of the album’s title? At that time both Wayne (in the band Weather Report) and Herbie (in both his Mwandishi and his Headhunters band) were invested in electronics and fusion. But here was a fusion recording that was acoustic. A real fusion of different worlds rather than merely a fusing of different approaches to the same world.

Native Dancer was not a novelty, in the sense of a unique variation on a well established theme. No, Native Dancer was something completely new. Where bossa nova had fused samba and cool jazz, this was another step toward oneness. Most jazz heads recognized instantly we were in the presence of a miracle.

When I turned over the record cover and saw that this Nascimento man had composed some of the music, needless to say, I knew what my next record purchase was going to be. That was in the mid-seventies, around 1975 or maybe (though I doubt it) as late as ’76—back then I was obsessive about staying current in jazz.

I did not know that Milton had already created a masterpiece with 1972’s Clube de Esquina (which we will deal with later). Nor did I know Milton had a great follow-up with 1973’s Milagre Dos Peixes, and even, for me, supremely impressive live recording with Milagre Dos Peixes: Gravado Ao Vivo, a May of 1974 concert. It’s like digging on Kind of Blue but not knowing Miles Ahead or any of the Prestige ‘Working’ sessions, or better yet, being bowled over by Stevie’s Musiquarium but not knowing Innervisions or Songs In The Key of Life.

Here I was thinking I was on top of what was going down when actually I was way behind the curve, way, way behind. Milton’s debut album had been in 1967, an American version on A&M is available as Milton Nascimento, sometimes as Travessia, not to be confused with the 1969 EMI Odeon release also titled Milton Nascimento, nor confused with the 1999 Brazilian Polygram release O Melhor de Milton Nascimento – Travessia (which, by the way is a good collection for starters but potentially confusing as it presents a number of alternate, rather than original, versions of major compositions).

Unraveling Milton’s discography would confuse Sherlock Holmes. Go here for a quick but no where near complete overview.

Milton has over thirty albums and at least seven or eight of them have the same titles although recorded at widely different times. He shares with many of his jazz colleagues a studious indifference to what labels record companies put on his music.

By the early eighties, determined to catch up, I’m in Brazil, walking down to the lower city in Salvador, Bahia (if you know Salvador, you know what I mean; if not, the city is on a mountainside up next to the water—they actually have an elevator to take you down, or up, from the lower to the upper city; Brazil will completely change your ideas about so-called urban life).

I spent hours in a record shop, listening, selecting, following both my ears and the sage advice of the guy behind the counter who didn’t speak much English but spoke fluent music, which was enough for he and I to communicate.

Back in the states I had a double armful of Milton Nascimento albums and started in. Eventually I copped everything by him I could find. Some of it I dug a lot, some I dug a little, one or two releases I only listened to once. Of course, many other Brazilian artists were added to my collection but none as frequently or as much as Milton Nascimento.

The vinyl is long gone but I have just about everything either in CD or on my hard drives. I’ve got two terabyte (that’s a thousand gigabytes) hard drives specifically dedicated to music, one is the main drive, the other is the backup. I believe the only artist I have more music by is John Coltrane—I go for every Coltrane second I can get. Miles runs a distant third behind Milton.

And that tells you both how much I dig Nascimento and why. He has the vibe of exploration and innovation that is a hallmark of the best of jazz.

Milton has over thirty albums and at least seven or eight of them have the same titles although recorded at widely different times. He shares with many of his jazz colleagues a studious indifference to what labels record companies put on his music.

By the early eighties, determined to catch up, I’m in Brazil, walking down to the lower city in Salvador, Bahia (if you know Salvador, you know what I mean; if not, the city is on a mountainside up next to the water—they actually have an elevator to take you down, or up, from the lower to the upper city; Brazil will completely change your ideas about so-called urban life).

I spent hours in a record shop, listening, selecting, following both my ears and the sage advice of the guy behind the counter who didn’t speak much English but spoke fluent music, which was enough for he and I to communicate.

Back in the states I had a double armful of Milton Nascimento albums and started in. Eventually I copped everything by him I could find. Some of it I dug a lot, some I dug a little, one or two releases I only listened to once. Of course, many other Brazilian artists were added to my collection but none as frequently or as much as Milton Nascimento.

The vinyl is long gone but I have just about everything either in CD or on my hard drives. I’ve got two terabyte (that’s a thousand gigabytes) hard drives specifically dedicated to music, one is the main drive, the other is the backup. I believe the only artist I have more music by is John Coltrane—I go for every Coltrane second I can get. Miles runs a distant third behind Milton.

And that tells you both how much I dig Nascimento and why. He has the vibe of exploration and innovation that is a hallmark of the best of jazz.

I can sing in Portuguese and still communicate with people who don't know the language. You can get your own feelings and images from the music, and when people do that, it makes me very happy. Every time I sing a song, it will have a different feeling for me, because the music changes as I change in my life. I work from the heart, and the heart speaks for itself. —Milton NascimentoThe basic ingredients of Milton’s music are indigenous to Brazil. The earth, the hills and mountains; the water, the rivers and ocean; the people, African, European and Native American; but it is also everything that has ever entered Brazil, not just goods, but also technology, not just people but also sounds. Oh, all the sounds of the world that ever arrived in Brazil howsoever those sounds got there, all those sounds are in Milton’s music. So we hear these songs, these chants, these symphonies, these magic moments. He would name it: “a teardrop of sun in the mouth of the night.” Even though he sings specifically of Brazil: we all can hear ourselves in his music. Who has not had a student’s heart—the heart of someone who is growing by learning? Who has not so closely identified with someone that they felt themselves to be the other and the other to be them, the two of us are the oneness of us? One disappointing afternoon who has not momentarily remembered the beauty of a promising dawn? Within the specifics of his world, Milton gets to the anima, the soul that animates everything in the world. Everything alive moves and all movement has a sound.

Milton has figured out how to make the sounds of emotions. He is a sound-a-tist. Yes. Scientists deal with the matter of the world. Soundatists, aka musical artists, deal with human emotions in the world.

Why else are some of us moved so profoundly by music from a man when we don’t know what the hell he is saying? (Even after his lyrics are translated they are often still Greek.)

It is better to feel the wonder of the world than to explain the workings of the world—and it is best to be able to do both even though we recognize that the brain is so limited next to the expansiveness of the heart.

Some have called jazz a very cerebral music, others think of jazz as a music of intense emotionality. The beauty of jazz is that it is both.

So this week, under classics, I present Milton as I first came to know and love him. I present Milton in his jazz context. Next week under classics I will focus on four specific Nascimento creations: the two Clube da Esquina releases and two ballet soundtracks (Maria, Maria and Ultima Trema) that were only recently made generally available.

For now, hear a man singing at the edge of his immense capabilities. Don’t worry about the lyrics, the language. Don’t bother trying to figure out how they are making those sounds. Don’t even try to count the beats or figure out the harmonies. Just feel with your ears.

Above all, hear his sound. His vibration. The range of his passions painting from a multicolored palette of human emotions. Clear melodies, complex but accessible harmonies and above all the rightness of his rhythms.

Milton has figured out how to make the sounds of emotions. He is a sound-a-tist. Yes. Scientists deal with the matter of the world. Soundatists, aka musical artists, deal with human emotions in the world.

Why else are some of us moved so profoundly by music from a man when we don’t know what the hell he is saying? (Even after his lyrics are translated they are often still Greek.)

It is better to feel the wonder of the world than to explain the workings of the world—and it is best to be able to do both even though we recognize that the brain is so limited next to the expansiveness of the heart.

Some have called jazz a very cerebral music, others think of jazz as a music of intense emotionality. The beauty of jazz is that it is both.

So this week, under classics, I present Milton as I first came to know and love him. I present Milton in his jazz context. Next week under classics I will focus on four specific Nascimento creations: the two Clube da Esquina releases and two ballet soundtracks (Maria, Maria and Ultima Trema) that were only recently made generally available.

For now, hear a man singing at the edge of his immense capabilities. Don’t worry about the lyrics, the language. Don’t bother trying to figure out how they are making those sounds. Don’t even try to count the beats or figure out the harmonies. Just feel with your ears.

Above all, hear his sound. His vibration. The range of his passions painting from a multicolored palette of human emotions. Clear melodies, complex but accessible harmonies and above all the rightness of his rhythms.

Those of us who hold microphones become the voice of those who do not have microphones. We have to alert others to what is happening in this world. We have to talk about preserving our planet, the earth, green things, animals, human beings--talk about how people treat each other. —Milton NascimentoMilton Nascimento was born on October 26, 1942 in Rio de Janeiro. His mother Maria do Carmo Nascimento was a singer who earned her survival as a maid. She died before Milton turned two. I don’t believe he ever met his biological father. A couple (Josino Brito Campos, a banker, math teacher and electronic technician, and Lilia Silva Campos, a music teacher and choir singer) his mother had worked for adopted him. So when he was four and moved from the coast to the interior of Brazil, to a small town call Tres Pontas in the hinterland state of Minas Gerais, Milton was born again. We would say, looking at it with American eyes, first he was black, then he was white. He knows that he did not come from his parents. He knows his parents came to him. Next week we will discuss his formative years and Milton’s assessment of his own uniqueness. Let me walk you through my jazz-oriented classic selections. The collaboration with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock is key. I don’t just mean Native Dancer, I mean if you listen you will notice that either together or singlely, Shorter and Hancock are on all but one of the jazz oriented albums that I am highlighting. Wayne immediately strikes. His soprano sound in particular is a startingly twin to Milton’s falsetto—startling because the sound wakes us up from predictability to envision innovative possibility: it is possible for men to mate musically, even when they are men of different cultures. As beautiful as Native Dancer is, I believe Wayne rises even higher on the April 1986 Sao Paulo concert recording A Barca Dos Amantes, from which “Nos Dois” and “Tarde” are taken. It helps that both melodies are exquisite but it is also the sway of the rhythms fitted to those handsome arcs of sound. Rhythm is the secret sauce in all of Milton’s recipes and Wayne’s solos float with such delight we are mesmerized. On “Saldas e Bandeiras (Exits and Flags)” Wayne is more earthy on tenor, down and dirty, dancing as it were flat foot on the dirt floor, his moves are more carnal though nonetheless subtle in their mastery of timing and tone. Sort of like how polite society looks askance at dancers who publicly shake their ass but deep down all those tsk-tskers are (or ought to be) envious; they know they can’t bounce their derriere like that, the uptight stewards of propriety just can’t make their bodies make those motions. You could point a loaded gun at them and they still couldn’t but their backfields in appropriate motion. So listen to the tenor of Mr. Shorter, there is no shortage of rump bumping. On “Bodas” that’s Nivaldo Ornelas on sax (and flute) and Robertinho Silva on drums. When I heard that opening I knew that they knew. Then Milton follows with a full throttle declaration of independence from fear, from hesitancy, from cowardice. Milton confronts the world: here I am. “Outubro” (October) is one of Milton’s signature songs. Here he out sings a full orchestra of over thirty musicians. Man I wish I had been in the Teatro Municipal do Sao Paulo on the seventh and eighth of May 1974 to witness this magnificent merger of jazz and classical music. Especially since Milton was at the top of his prowess as a vocalist; don’t miss that last note on “Outubro.” And less someone think I am exaggerating, think I am just throwing words on paper as journalists do when they are trying to impress readers, check out what Milton had to say in an interview for Fader magazine about these times and that recordings. Milton starts of speaking about the album 1973 Milagro Dos Peixes and then references the subsequent 1974 concert from which the live album was taken:

This album was a cry against the violence against our lives and it was conceived at the worst point in my life. We lived under a very cruel dictatorship and many artists were forced to leave the country. I decided to stay and that was very hard to deal with. I just received a copy of some footage from two concerts we did in Sao Paulo for a live version of this album in 1974. One night I played with a symphonic orchestra and the next day I played for 50,000 students. It was magic.The legend is that when Milton first released Milagro Dos Peixes, he stripped off most of the lyrics as a protest against government censorship. What was left was mostly pure sounds, sounds that unmistakably declared opposition to government death and oppression. Is it any wonder that Milton was regarded as Brazil’s most important artist of his era? Milton’s voice was literally Brazil’s cry. Listen again to “A Chamada,” which first appeared on Milagro Dos Peixes; listen and understand what Milton meant when he told writer Pamela Bloom in an interview published in Musician magazine that the Nascimento solution to government censorship was to “tranform my voice into an instrument. We’d write something, the censors would send it back, stamped No Way. We’d have to write the same thing in a way that the censors wouldn’t notice but the people would understand.”

The silence of slaves, the muteness of the downpressed is not consent to their conditions but rather an unuttered cry for release, for freedom. Milton’s voice expresses that.

At the core of jazz is the freedom of spontaneous creation. I think it is this freedom, more than any particular musical element, that Wayne Shorter and many other jazz musicians empathize with in Nascimento’s music. If you understand the freedom principal then there is no surprise in Milton’s jazz connection.

To fully illustrate the difference, I also include the original version of “A Chamada” from Milagre dos Peixes. As beautiful as the 1976 American recording is, that version is denuded of the political context and thus is abstracted into something simply beautiful: we do not see the scars on the body because of the silk raiment covering the welts and wounds.

You can hear so much more when you know what you’re listening to.

The second version in the jukebox, the original 1973 recording, sounds like 1973 jazz did—all those wild voices, everything is there. While the American version is simply beautiful, the original is complexly beautiful. One is a beauty to relax to, the original is a beauty that encourages struggle. We need both today. I am so glad Milton understands both the complexity of life and also knows when and how to keep it simple.

The silence of slaves, the muteness of the downpressed is not consent to their conditions but rather an unuttered cry for release, for freedom. Milton’s voice expresses that.

At the core of jazz is the freedom of spontaneous creation. I think it is this freedom, more than any particular musical element, that Wayne Shorter and many other jazz musicians empathize with in Nascimento’s music. If you understand the freedom principal then there is no surprise in Milton’s jazz connection.

To fully illustrate the difference, I also include the original version of “A Chamada” from Milagre dos Peixes. As beautiful as the 1976 American recording is, that version is denuded of the political context and thus is abstracted into something simply beautiful: we do not see the scars on the body because of the silk raiment covering the welts and wounds.

You can hear so much more when you know what you’re listening to.

The second version in the jukebox, the original 1973 recording, sounds like 1973 jazz did—all those wild voices, everything is there. While the American version is simply beautiful, the original is complexly beautiful. One is a beauty to relax to, the original is a beauty that encourages struggle. We need both today. I am so glad Milton understands both the complexity of life and also knows when and how to keep it simple.

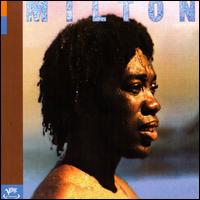

I'm used to being the friend of my songwriting partners. So I would get there to the United States, and first you had to talk with the agent, then the publishing company, then the lawyer. The last thing would be the person himself, and by then I'd generally be tired and discouraged. —Milton NascimentoYes, Milton lived in Brazil during most of the dictatorship but it was not because he did not have an opportunity to leave. In fact in 1968, less than two years after his career took off in Brazil, Milton was recording an album in Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studios for CTI records. A&M thought they had the next Jobim, the leader of the next Brazilian wave after bossa nova. The title of the album: Courage. Ironic, isn’t it? In some ways America drove Milton back to his comrades in Brazil, like Harriet Tubman returning south, Milton returned to Brazil to face the music of his life experiences and produce his masterpieces in collaboration with old friends. Oh, by the way, Herbie Hancock played piano on that 1969 session, recording with Nascimento long before Wayne Shorter did although Shorter’s Native Dancer is usually pointed to not only as Nascimento’s jazz introduction but also as Nascimento’s first major collaboration. The truth is far, far different from the conventional wisdom. Moreover, as far as Nascimento’s work with American jazz musicians goes, the brilliance of the Wayne Shorter collaboration notwithstanding, it is Herbie Hancock’s contributions that surprise me the most. I have not been a big, big fan of Herbie as a piano soloist. I love, respect and admire his compositional talents and his sensitive accompaniment to others, and recognize that he is an important band leader, but his soloing never rose to the heights of the masterful except when he is playing with Milton and especially every time Hancock takes flight on Miltons, the 1989 Columbia recording. If I had to take one Milton Nascimento recording to heaven (or wherever pleasant one goes after death—there is no music in hell, no music!), it would be Miltons. Listen to those gracefully passionate piano solos, especially on “San Vicente” but also on everything else on the record. The elegance of “Don Quixote” is extremely attractive and the stately abstractness and dexterity of Herbie’s staccato figures on "Like Us" reminds me of a straight up flamingo dancer. But on “San Vincente” Herbie is dancing, full out, using all his moves. This is possibly Herbie’s single best solo on record. Notice at the halfway mark how they drop out all the other musicians, just Herbie atop Milton’s rhythm guitar. You can hear them growling, literally, they are making those sounds one makes when you exert yourself with everything you have. Herbie’s hands dance with almost demonic exaltation. What a sublime duet. Damn.

And that’s how I fell, head over heels, inescapably, "don’t save me cause I ain’t dying, I‘m simply and voluntarily, blissfully drowning in Milton’s musical sea." If I don’t make it back to shore, so be it. So what. Ask Herbie, he knows. He’s been out there a minute, awash in this beautiful, beautiful whirl of Nascimento sounds.

To be continuted… (next week, the Brazilian classics).

And that’s how I fell, head over heels, inescapably, "don’t save me cause I ain’t dying, I‘m simply and voluntarily, blissfully drowning in Milton’s musical sea." If I don’t make it back to shore, so be it. So what. Ask Herbie, he knows. He’s been out there a minute, awash in this beautiful, beautiful whirl of Nascimento sounds.

To be continuted… (next week, the Brazilian classics).

I don’t understand longing for a path That ended long ago I still have unexplored lines on my palm And they are numerous, innumerable No one has yet unveiled the news Even the wisest of men Still asks himself Where did I come from? Teach me to feel! —from Don Quixote by Cesar Camargo Mariano and Milton NascimentoI’m going to make it easy to get your Nascimento on. Here are five albums (and their covers so you can see what your are doing), one for each finger on your hand. Here we count like little childen; one, two, three, four, FIVE!

1. Milagre Dos Peixes – Ao Vivo (EMI 1974)

Contains “Bodas” and “Outubro”

This is one of Milton's proudest moments. Democracy was still a decade away. The miltary was running things. Now listen again to that opening on "Bodas." Got it? This album clarified for me that Milton was far, far beyond pop music or even sentimental paens to his homeland. This was music deeply involved in the struggles of its day.

1. Milagre Dos Peixes – Ao Vivo (EMI 1974)

Contains “Bodas” and “Outubro”

This is one of Milton's proudest moments. Democracy was still a decade away. The miltary was running things. Now listen again to that opening on "Bodas." Got it? This album clarified for me that Milton was far, far beyond pop music or even sentimental paens to his homeland. This was music deeply involved in the struggles of its day.

2. Wayne Shorter, Native Dancer (Columbia – 1974)

Contains “Ponta De Areia”

A jazz classic; pure and simple. If you don't have it, get it; if you do have it, listen to it again.

2. Wayne Shorter, Native Dancer (Columbia – 1974)

Contains “Ponta De Areia”

A jazz classic; pure and simple. If you don't have it, get it; if you do have it, listen to it again.

3. Milton – (Verve-A&M – 1976)

Contains “The Call (A Chamada)” and “Saidas e Bandeiras (Exits and Flags)”

This is one of the best albums Milton cut in the United States. Both Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock are on this one, plus it includes wonderfully realized versions of a number of Milton's signature compositions.

3. Milton – (Verve-A&M – 1976)

Contains “The Call (A Chamada)” and “Saidas e Bandeiras (Exits and Flags)”

This is one of the best albums Milton cut in the United States. Both Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock are on this one, plus it includes wonderfully realized versions of a number of Milton's signature compositions.

4. A Barca Dos Amantes – Verve – 1986)

Contains “Nos Dois” and “Tarde”

Except for Wayne Shorter, all the musicians here are South American. Joining Milton are Ricardo Silveira on guitar, Luiz Avellar on keys, Nico Assumpacao on electric bass, Robertinho Silva on drums and percussion. Wayne Shorter plays on three cuts. It's out of print right now so it's either hard to find or very expensive when you do find it.

4. A Barca Dos Amantes – Verve – 1986)

Contains “Nos Dois” and “Tarde”

Except for Wayne Shorter, all the musicians here are South American. Joining Milton are Ricardo Silveira on guitar, Luiz Avellar on keys, Nico Assumpacao on electric bass, Robertinho Silva on drums and percussion. Wayne Shorter plays on three cuts. It's out of print right now so it's either hard to find or very expensive when you do find it.

5. Miltons (Columbia – 1989)

Contains “Don Quixote,” “Like Us (Feito Nos)” and “San Vicente”

This is absolute, without any doubt nor reservations the best album Milton cut in the USA. Inspired and Herbie Hancock out does himself. Absolute gorgeous (I'm repeating myself but really, it's just that good.)! The basic band is all-star trio: Milton on vocals and guitar (you get to hear more of his guitar playing on this album than is usually presented), Brazil master percussionist Nana Vasconcelos (who also adds vocals to the mix), and Herbie Hancock on piano and synthesized bass. Drummer Robertinho Silva plays on two cuts and bassist Joao Baptista plays on one cut. There are also two choruses: an adult choir of six voices and a children's chorus also containing six voices. Over twenty years after his 1967 debut, Milton delivers an amazing collection of music. This is a gem.

5. Miltons (Columbia – 1989)

Contains “Don Quixote,” “Like Us (Feito Nos)” and “San Vicente”

This is absolute, without any doubt nor reservations the best album Milton cut in the USA. Inspired and Herbie Hancock out does himself. Absolute gorgeous (I'm repeating myself but really, it's just that good.)! The basic band is all-star trio: Milton on vocals and guitar (you get to hear more of his guitar playing on this album than is usually presented), Brazil master percussionist Nana Vasconcelos (who also adds vocals to the mix), and Herbie Hancock on piano and synthesized bass. Drummer Robertinho Silva plays on two cuts and bassist Joao Baptista plays on one cut. There are also two choruses: an adult choir of six voices and a children's chorus also containing six voices. Over twenty years after his 1967 debut, Milton delivers an amazing collection of music. This is a gem.

This entry was posted on Monday, August 4th, 2008 at 5:08 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

2 Responses to “MILTON NASCIMENTO / “San Vicente””

August 10th, 2008 at 11:07 am

I remeber when “Miltons” was released, thinking ‘Why doesn’t Herbie play like this on his own records?’ Great selection of Milton recordings! Thanks.

July 12th, 2017 at 3:50 pm

I just learned about Clube da Esquina, which was introduced to me through our local jazz station in San Antonio, TX. As I’ve listed to more and more of the first, self-titled record, I have become increasingly a fan of Milton’s. And like you write above, through musical and emotive vibrations he speaks to my perspective on life. Thanks for the recommendations–I look forward to hearing more of his stuff.

Leave a Reply

| top |