MELLE MEL & DUKE BOOTEE / “Message II (Survival)”

I thought I was finished with the “city” theme, but over the past weekend I started thinking about a tetralogy* of city songs from the world of rap. All four prominently feature legendary hip-hop MC Melle Mel and all four are about Melle Mel’s hometown – and the birthplace of rap music — New York City. These songs have fascinating histories, so let’s break them down in chronological order.

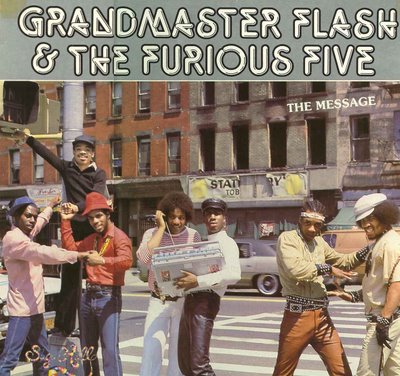

1. Grand Master Flash & The Furious Five feat. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee – “The Message” – Originally released as a 12” single (Sugar Hill, 1982); Available on Message From Beat Street: The Best Of Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel & The Furious Five (Rhino, 1994)

1. Grand Master Flash & The Furious Five feat. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee – “The Message” – Originally released as a 12” single (Sugar Hill, 1982); Available on Message From Beat Street: The Best Of Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel & The Furious Five (Rhino, 1994)

This record is credited to “Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five,” so it’s natural to assume that it’s performed by – oh, I don’t know – Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five. It isn’t. The principal creative force behind one of the greatest songs in the history of recorded rap wasn’t (and still isn’t) particularly well known and wasn’t even a rapper.

This record is credited to “Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five,” so it’s natural to assume that it’s performed by – oh, I don’t know – Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five. It isn’t. The principal creative force behind one of the greatest songs in the history of recorded rap wasn’t (and still isn’t) particularly well known and wasn’t even a rapper.

Back in the early Eighties, a guy named Edward Fletcher was the percussionist for the Sugar Hill Gang (of “Rapper’s Delight” fame). Working on his own, he came up with a percussion-heavy groove (a Last Poets-sounding workout that would eventually become the backing track for “The Message”) and a hook to go along with it (“It’s like a jungle sometimes / It makes me wonder how I keep from going under”). Edward brought the track to his boss, the head of Sugar Hill Records, Sylvia Robinson. Sylvia thought it had hit potential and therefore decided to record it. That’s about all anyone can agree on. The rest of the story is murky.

To hear Sylvia tell it, she re-arranged, added on to, co-wrote and produced it, along the way encouraging, convincing and coercing a reluctant Ed Fletcher and Melle Mel into participating in the final product. (A representative example of that version of the story is available here.)

Of course, that isn’t the story I heard. Straight from the horse’s mouth (or one of them, at least) I was told that Ed Fletcher showed up in the studio with “The Message” virtually complete – lyrics, vocals and backing track. The only problem was, the conga-heavy track coupled with Ed’s prosaic style of talk-rapping made the demo sound more like spoken word than hip-hop. Despite that, Sylvia Robinson thought “The Message” could be big. Sylvia gets a lot of grief for underpaying her artists, and rightfully so, but one thing everyone agrees on is her business acumen and her ear for a hit. Everyone I’ve spoken to on the subject says (or admits) that Sylvia is the one person at Sugar Hill who was convinced “The Message” would be big. Strangely enough, she wanted to release it as a Grandmaster Flash record, this despite the fact that neither Flash nor his five MCs had anything to do thus far with creating the song.

Back in the early Eighties, a guy named Edward Fletcher was the percussionist for the Sugar Hill Gang (of “Rapper’s Delight” fame). Working on his own, he came up with a percussion-heavy groove (a Last Poets-sounding workout that would eventually become the backing track for “The Message”) and a hook to go along with it (“It’s like a jungle sometimes / It makes me wonder how I keep from going under”). Edward brought the track to his boss, the head of Sugar Hill Records, Sylvia Robinson. Sylvia thought it had hit potential and therefore decided to record it. That’s about all anyone can agree on. The rest of the story is murky.

To hear Sylvia tell it, she re-arranged, added on to, co-wrote and produced it, along the way encouraging, convincing and coercing a reluctant Ed Fletcher and Melle Mel into participating in the final product. (A representative example of that version of the story is available here.)

Of course, that isn’t the story I heard. Straight from the horse’s mouth (or one of them, at least) I was told that Ed Fletcher showed up in the studio with “The Message” virtually complete – lyrics, vocals and backing track. The only problem was, the conga-heavy track coupled with Ed’s prosaic style of talk-rapping made the demo sound more like spoken word than hip-hop. Despite that, Sylvia Robinson thought “The Message” could be big. Sylvia gets a lot of grief for underpaying her artists, and rightfully so, but one thing everyone agrees on is her business acumen and her ear for a hit. Everyone I’ve spoken to on the subject says (or admits) that Sylvia is the one person at Sugar Hill who was convinced “The Message” would be big. Strangely enough, she wanted to release it as a Grandmaster Flash record, this despite the fact that neither Flash nor his five MCs had anything to do thus far with creating the song.

Further complicating matters, Grandmaster Flash himself was quickly becoming persona non grata around the Sugar Hill studios. To understand why, we have to stand back a minute. Flash was one of the most famous and certainly the most skillful of all the pre-record era hip-hop DJs. But once rap music moved to the recording studio, house bands took the place of the DJ. Flash was left jobless. Sylvia couldn’t just give Flash the boot though – she needed his name. She also needed his old park routines. What she began to do was remake Flash’s old music by having her in-house band re-play the breaks Flash used when he performed live. Then, Flash’s MCs would perform their lyrics over the newly-recorded tracks. Oftentimes, Flash wasn’t even in the recording studio when the band was replaying his mixes or when his MCs were laying down vocals for the records that would end up bearing his name.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, none of the six members of the band were getting paid royalties. If they got paid anything, it seemed to be on a ‘per complaint’ basis. Flash and his MCs usually received somewhere between $500 and $1,000 per track, and that’s if they got anything at all. This includes numerous records that sold in the hundreds of thousands and at least one that went gold. (When it comes to Sugar Hill, specific and creditable sales figures are hard to come by. Not unintentionally either.) In part because they were getting short-changed for recorded output, the band made most of their money from live performances. Of course, they promptly wasted almost all of it on motorcycles, cars, clothes and, of course, drugs – lots and lots of drugs. (On at least one occasion they were paid for a nightclub performance in cocaine instead of money.) Needless to say, feelings were hurt and relationships were strained. The lawsuits and breakups were virtually inevitable.

But back to “The Message.” In order to pull off the switch and make a hit out of what was essentially a demo by the Sugar Hill Gang’s percussionist, Sylvia Robinson knew she had to get at least one member of Grandmaster Flash’s MCs on the record. The only problem was, none of them were interested.

Further complicating matters, Grandmaster Flash himself was quickly becoming persona non grata around the Sugar Hill studios. To understand why, we have to stand back a minute. Flash was one of the most famous and certainly the most skillful of all the pre-record era hip-hop DJs. But once rap music moved to the recording studio, house bands took the place of the DJ. Flash was left jobless. Sylvia couldn’t just give Flash the boot though – she needed his name. She also needed his old park routines. What she began to do was remake Flash’s old music by having her in-house band re-play the breaks Flash used when he performed live. Then, Flash’s MCs would perform their lyrics over the newly-recorded tracks. Oftentimes, Flash wasn’t even in the recording studio when the band was replaying his mixes or when his MCs were laying down vocals for the records that would end up bearing his name.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, none of the six members of the band were getting paid royalties. If they got paid anything, it seemed to be on a ‘per complaint’ basis. Flash and his MCs usually received somewhere between $500 and $1,000 per track, and that’s if they got anything at all. This includes numerous records that sold in the hundreds of thousands and at least one that went gold. (When it comes to Sugar Hill, specific and creditable sales figures are hard to come by. Not unintentionally either.) In part because they were getting short-changed for recorded output, the band made most of their money from live performances. Of course, they promptly wasted almost all of it on motorcycles, cars, clothes and, of course, drugs – lots and lots of drugs. (On at least one occasion they were paid for a nightclub performance in cocaine instead of money.) Needless to say, feelings were hurt and relationships were strained. The lawsuits and breakups were virtually inevitable.

But back to “The Message.” In order to pull off the switch and make a hit out of what was essentially a demo by the Sugar Hill Gang’s percussionist, Sylvia Robinson knew she had to get at least one member of Grandmaster Flash’s MCs on the record. The only problem was, none of them were interested.

There’s one famous quote by Melle Mel where he says, “No one wants to take their problems to a disco.” And the other four members of the Furious Five didn’t like Ed Fletcher’s demo any more than Mel did. Make that the other five members – Flash wasn’t going to be on the record anyway (he didn’t rap and aside from the epochal “The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash,” scratching simply wasn’t done on wax back then) but he agreed with his MCs, “The Message” was a disaster waiting to happen. Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five was a party group and hip-hop was party music. A hip-hop jam was about temporarily escaping from the harsh reality of life in the urban ghettos. Who the hell wanted to party to reality?

The turning point came when one of the Furious Five realized that Mel had already done a “message rap” of sorts. The Furious Five’s first record was a sprawling jam named “Superrappin’” that was released in 1979 on Bobby Robinson's (no relation to Sylvia) Enjoy label. Near the end of “Superrappin’,” Mel launches into a long, narrative-style rap that begins, “A child is born….” It’s a brilliant bit of lyrics – in just one verse it encapsulates the hopes, dreams, struggles and ultimate failure of one ghetto child turned man. You’d have to listen closely to even catch what Mel is saying though. The lyrics are buried between more commonplace lines about partying, making lots of money, seducing the ladies and being an all-around great guy. And even if you catch the lyrics, you might still be unimpressed because Mel performs the verse in an almost breathless jumble, as if he’s trying to get it over with as quickly as possible. Before “Superrappin’,” no one had ever performed a so-called “message rap.” Melle Mel may have been breaking new ground but he doesn’t sound particularly comfortable doing it.

Ultimately, Sylvia decided to go ahead with the recording. Melle Mel and Ed Fletcher performed Ed’s lyrics; the Sugar Hill house band came up with a re-arranged and modernized version of Ed’s track (along with a spooky and sinister keyboard line that was added in later); and Mel ended the record with his verse from “Superrappin’.” When it was finally released, the record was billed as “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five featuring Melle Mel and Duke Bootee. “Duke Bootee” is Ed Fletcher.

2. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee – “Message II (Survival)” – Originally released as a 12” single (Sugar Hill, 1982); Available on Message From Beat Street: The Best Of Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel & The Furious Five (Rhino, 1994)

It’s easy to wonder today how Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five MCs could have been so off-base about the hit-potential of what eventually became their signature song. Part of the answer to that question is these six pioneers were still coming to grips with their music being recorded at all! For them, hip-hop was live music, club music, park music. And not just that, it wasn’t really even music, per se. I’ve talked to Old School MCs, DJs and b-boys (dancers) who said they never thought they were “doing” anything and they never called what they did “music.” They’d say, “We’re going to the jam” or “Let’s do our thing.” And then they’d do it. The names given to the participants reflect the ambivalence – this was no orchestrated “scene” or “happening.” People were just doing their thing.

There’s one famous quote by Melle Mel where he says, “No one wants to take their problems to a disco.” And the other four members of the Furious Five didn’t like Ed Fletcher’s demo any more than Mel did. Make that the other five members – Flash wasn’t going to be on the record anyway (he didn’t rap and aside from the epochal “The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash,” scratching simply wasn’t done on wax back then) but he agreed with his MCs, “The Message” was a disaster waiting to happen. Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five was a party group and hip-hop was party music. A hip-hop jam was about temporarily escaping from the harsh reality of life in the urban ghettos. Who the hell wanted to party to reality?

The turning point came when one of the Furious Five realized that Mel had already done a “message rap” of sorts. The Furious Five’s first record was a sprawling jam named “Superrappin’” that was released in 1979 on Bobby Robinson's (no relation to Sylvia) Enjoy label. Near the end of “Superrappin’,” Mel launches into a long, narrative-style rap that begins, “A child is born….” It’s a brilliant bit of lyrics – in just one verse it encapsulates the hopes, dreams, struggles and ultimate failure of one ghetto child turned man. You’d have to listen closely to even catch what Mel is saying though. The lyrics are buried between more commonplace lines about partying, making lots of money, seducing the ladies and being an all-around great guy. And even if you catch the lyrics, you might still be unimpressed because Mel performs the verse in an almost breathless jumble, as if he’s trying to get it over with as quickly as possible. Before “Superrappin’,” no one had ever performed a so-called “message rap.” Melle Mel may have been breaking new ground but he doesn’t sound particularly comfortable doing it.

Ultimately, Sylvia decided to go ahead with the recording. Melle Mel and Ed Fletcher performed Ed’s lyrics; the Sugar Hill house band came up with a re-arranged and modernized version of Ed’s track (along with a spooky and sinister keyboard line that was added in later); and Mel ended the record with his verse from “Superrappin’.” When it was finally released, the record was billed as “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five featuring Melle Mel and Duke Bootee. “Duke Bootee” is Ed Fletcher.

2. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee – “Message II (Survival)” – Originally released as a 12” single (Sugar Hill, 1982); Available on Message From Beat Street: The Best Of Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel & The Furious Five (Rhino, 1994)

It’s easy to wonder today how Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five MCs could have been so off-base about the hit-potential of what eventually became their signature song. Part of the answer to that question is these six pioneers were still coming to grips with their music being recorded at all! For them, hip-hop was live music, club music, park music. And not just that, it wasn’t really even music, per se. I’ve talked to Old School MCs, DJs and b-boys (dancers) who said they never thought they were “doing” anything and they never called what they did “music.” They’d say, “We’re going to the jam” or “Let’s do our thing.” And then they’d do it. The names given to the participants reflect the ambivalence – this was no orchestrated “scene” or “happening.” People were just doing their thing.

MCs were called MCs because the guy with the microphone at a party or event is the “master of ceremonies,” the MC. The DJ is the disc jockey, the guy who plays the records. B-boys were “break boys,” the guys who could dance the best when the DJ played the “breaks” – the funky bits of drum, bass guitar and percussion that frequently show up on Seventies funk, soul and jazz records. Once MCs started talking over the music, it was called “rapping” only because that was an already-existing slang for talking. There’s a phrase you’ll hear a lot in Old School hip-hop: “rapping to the beat.” All it meant was, talking over a rhythm. The point I’m trying to make is, none of this was planned. Most of the terms that we now think of as being “hip-hop” were already around. Rapping, DJ, MC, break-boy (or b-boy for short) – those were all references to things that already existed. When it comes to hip-hop (and really, black music in general), asking who invented what is to miss the point.

With all of that in mind, it’s easier to understand Flash and the MCs’ reluctance to record a “serious” rap record. In less than three years, they’d gone from being the kings of the party scene, local heroes, ghetto superstars, to suddenly recording and selling hundreds and hundreds of thousands of copies of their old park routines. They were flying around the world, performing in countries they’d never heard of, seeing sights they’d never imagined, and yet they were barely even adults – all of them were still in their late teens and early twenties. (At the ripe old age of 24, Flash was the elder statesmen of the group.) When they came back from their tours, they’d go back to the same ghetto tenements where they’d lived with their mothers before they became famous. It had to be a crazy life, something like watching one’s self live a fantasy/nightmare from which their was no waking up.

MCs were called MCs because the guy with the microphone at a party or event is the “master of ceremonies,” the MC. The DJ is the disc jockey, the guy who plays the records. B-boys were “break boys,” the guys who could dance the best when the DJ played the “breaks” – the funky bits of drum, bass guitar and percussion that frequently show up on Seventies funk, soul and jazz records. Once MCs started talking over the music, it was called “rapping” only because that was an already-existing slang for talking. There’s a phrase you’ll hear a lot in Old School hip-hop: “rapping to the beat.” All it meant was, talking over a rhythm. The point I’m trying to make is, none of this was planned. Most of the terms that we now think of as being “hip-hop” were already around. Rapping, DJ, MC, break-boy (or b-boy for short) – those were all references to things that already existed. When it comes to hip-hop (and really, black music in general), asking who invented what is to miss the point.

With all of that in mind, it’s easier to understand Flash and the MCs’ reluctance to record a “serious” rap record. In less than three years, they’d gone from being the kings of the party scene, local heroes, ghetto superstars, to suddenly recording and selling hundreds and hundreds of thousands of copies of their old park routines. They were flying around the world, performing in countries they’d never heard of, seeing sights they’d never imagined, and yet they were barely even adults – all of them were still in their late teens and early twenties. (At the ripe old age of 24, Flash was the elder statesmen of the group.) When they came back from their tours, they’d go back to the same ghetto tenements where they’d lived with their mothers before they became famous. It had to be a crazy life, something like watching one’s self live a fantasy/nightmare from which their was no waking up.

As soon as “The Message” hit big – which was immediately after its release – the search was on for another record just like it. Luckily for Sylvia Robinson, an MC named Spoonie G who she’d recently lured from Enjoy (the same label that Flash and The Five began on) was working on a message rap of his own. He called it “Survival.” His record was modeled after “The Message” – it had a half-chanted refrain just like its predecessor and the lyrics had a similar feel as well. (The refrain was important because it gave non-hardcore fans something easy to remember and simple to “sing” along too.)

In the wake of the success of “The Message,” Spoonie knew he had something major on his own hands. The only problem was, it was becoming more and more obvious to everyone involved that the artists at Sugar Hill simply weren’t getting paid. Spoonie knew this first hand; he’d already recorded several local and regional hits with Sugar Hill. Along the way he’d learned that he wasn’t going to get rich (or even financially stable) via Sylvia Robinson’s company no matter how many records he sold. The money simply never made its way down to the artist. The bottom line is, Spoonie wanted out.

Unfortunately, he’d been so eager to join Sugar Hill that he’d signed a horrible contract, one that basically gave Sylvia and Co. the complete rights to anything he recorded or wrote for several years to come. Perhaps Spoonie could’ve held out or tried to sue to gain his release from the label, but you have to remember, in a confrontation between a well-established record company and a young, inexperienced artist, the record company holds almost all of the cards. In short, Spoonie agreed to give up the rights to his new message song in return for a release from his contract.

Hoping to strike gold twice, Sylvia quickly tapped Mel and Ed to re-record Spoonie’s lyrics in the same style that they’d done on “The Message.” The tactic worked. Released later in the same year as the song that inspired it, “Message II (Survival)” by Melle Mel & Duke Bootee hit the airwaves hard, becoming an immediate hit. Of course, it helped that “Survival” sounded like a virtual extension of the massively popular “The Message.” At the end of the new record, Melle Mel even reprised the first few bars of his “child his born” rap, making “Message II (Survival)” the third recording in less than three years that featured those same lyrics.

Next week, more on the strange behind-the-scenes goings on at Sugar Hill Records and two more classic message raps featuring Melle Mel.

—Mtume ya Salaam

* Notice how I threw that word in there as if it’s part of my normal vocabulary? I actually just learned it today. A tetralogy is a series of four related dramatic, operatic, or literary works.

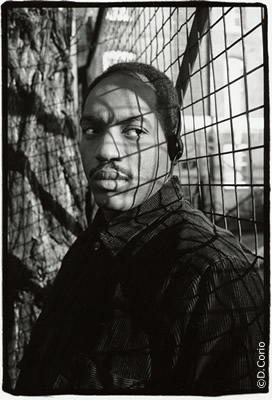

The Art of Rap

Once upon a time in a faraway land named for a powerful woman (or so the story goes), a land of eternal sunshine, of both mountains and beaches, green valleys and productive farm land, a land at the end of the new world where one could find a new life; once upon a time a young man crashed through the cotton curtain of the Deep South, the murky morass of Louisiana swamps and bayous and went to this new land. By day (and sometimes by night) the young man drove trucks to support his family but in his heart lived the spirit of a writer. And because this ‘once upon a time’ young man was interested in (‘interested’?—no, he was damn near obsessed with) the new music called “rap,” the young man began to study the music. He read nearly everything that was written, he tracked down many of the founding fathers (& even a few mothers) and interviewed them. This young man undertook a mission.

The far away land was California. The daring young man is Mtume ya Salaam. And the mission was a book to be called: The Art of Rap—the goal was to write a history of recorded rap.

Mtume, bit by bit, it would be good if you would go on and drop The Art of Rap.

Folks, what we have with this look at “The Message,” is a mere morsel, a teaser, perhaps even a trailer for The Art of Rap. Mtume, I encourage you to share what you have. It may never be finished to your satisfaction, but even in its present state, The Art of Rap would greatly aid our enlightenment.

If, like me, BoL fans want to read more of Mtume writing about rap, please hit Mtume an email at: mtume_s@yahoo.com

—Kalamu ya Salaam

As soon as “The Message” hit big – which was immediately after its release – the search was on for another record just like it. Luckily for Sylvia Robinson, an MC named Spoonie G who she’d recently lured from Enjoy (the same label that Flash and The Five began on) was working on a message rap of his own. He called it “Survival.” His record was modeled after “The Message” – it had a half-chanted refrain just like its predecessor and the lyrics had a similar feel as well. (The refrain was important because it gave non-hardcore fans something easy to remember and simple to “sing” along too.)

In the wake of the success of “The Message,” Spoonie knew he had something major on his own hands. The only problem was, it was becoming more and more obvious to everyone involved that the artists at Sugar Hill simply weren’t getting paid. Spoonie knew this first hand; he’d already recorded several local and regional hits with Sugar Hill. Along the way he’d learned that he wasn’t going to get rich (or even financially stable) via Sylvia Robinson’s company no matter how many records he sold. The money simply never made its way down to the artist. The bottom line is, Spoonie wanted out.

Unfortunately, he’d been so eager to join Sugar Hill that he’d signed a horrible contract, one that basically gave Sylvia and Co. the complete rights to anything he recorded or wrote for several years to come. Perhaps Spoonie could’ve held out or tried to sue to gain his release from the label, but you have to remember, in a confrontation between a well-established record company and a young, inexperienced artist, the record company holds almost all of the cards. In short, Spoonie agreed to give up the rights to his new message song in return for a release from his contract.

Hoping to strike gold twice, Sylvia quickly tapped Mel and Ed to re-record Spoonie’s lyrics in the same style that they’d done on “The Message.” The tactic worked. Released later in the same year as the song that inspired it, “Message II (Survival)” by Melle Mel & Duke Bootee hit the airwaves hard, becoming an immediate hit. Of course, it helped that “Survival” sounded like a virtual extension of the massively popular “The Message.” At the end of the new record, Melle Mel even reprised the first few bars of his “child his born” rap, making “Message II (Survival)” the third recording in less than three years that featured those same lyrics.

Next week, more on the strange behind-the-scenes goings on at Sugar Hill Records and two more classic message raps featuring Melle Mel.

—Mtume ya Salaam

* Notice how I threw that word in there as if it’s part of my normal vocabulary? I actually just learned it today. A tetralogy is a series of four related dramatic, operatic, or literary works.

The Art of Rap

Once upon a time in a faraway land named for a powerful woman (or so the story goes), a land of eternal sunshine, of both mountains and beaches, green valleys and productive farm land, a land at the end of the new world where one could find a new life; once upon a time a young man crashed through the cotton curtain of the Deep South, the murky morass of Louisiana swamps and bayous and went to this new land. By day (and sometimes by night) the young man drove trucks to support his family but in his heart lived the spirit of a writer. And because this ‘once upon a time’ young man was interested in (‘interested’?—no, he was damn near obsessed with) the new music called “rap,” the young man began to study the music. He read nearly everything that was written, he tracked down many of the founding fathers (& even a few mothers) and interviewed them. This young man undertook a mission.

The far away land was California. The daring young man is Mtume ya Salaam. And the mission was a book to be called: The Art of Rap—the goal was to write a history of recorded rap.

Mtume, bit by bit, it would be good if you would go on and drop The Art of Rap.

Folks, what we have with this look at “The Message,” is a mere morsel, a teaser, perhaps even a trailer for The Art of Rap. Mtume, I encourage you to share what you have. It may never be finished to your satisfaction, but even in its present state, The Art of Rap would greatly aid our enlightenment.

If, like me, BoL fans want to read more of Mtume writing about rap, please hit Mtume an email at: mtume_s@yahoo.com

—Kalamu ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, June 29th, 2008 at 11:59 pm and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

One Response to “MELLE MEL & DUKE BOOTEE / “Message II (Survival)””

January 21st, 2012 at 11:46 am

it is so sad that rappers and djs that paved the way for todays mcs didnt make money.

Leave a Reply

| top |