MILES DAVIS / “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)”

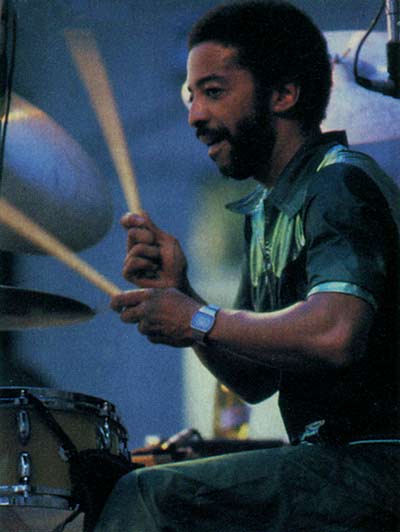

Since Miles was the nominal leader, all this music is under the Davis name; but be not deceived, Tony Williams is both the fuel and the engine. Undoubtedly Miles designed the starship and, knowing full well what each of them could do, Miles picked the crew. Nevertheless, once they started, whether playing full out at thunderous levels or dropping completely out, the pulse was dictated by the drums of Tony Williams.

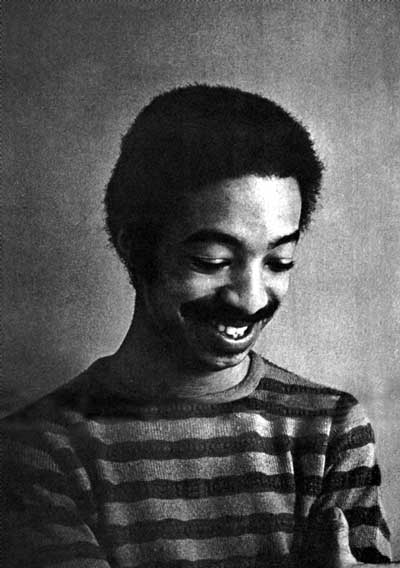

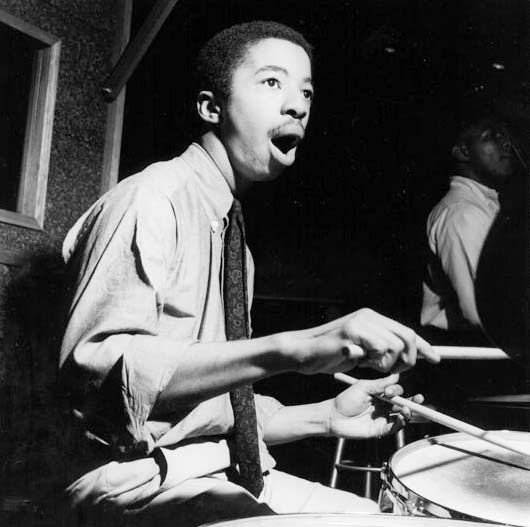

Anthony Tillmon Williams was born in 1945 in Chicago. His family moved to Boston where he was reared. He took up drums while in third grade. Before he was out of high school he was sitting in with musicians around Boston. Miles hired him when he was 18. The rest is legend.

I want to speak about ying/yang in the mode of Miles. I see three major periods in Miles’ music. 1. Everything up to Kind of Blue (1959). 2. Everything between Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew (1969). 3. Everything after Bitches Brew—this later period Miles has two parts: pre-retirement and post-retirement. The ying/yang mode comes mostly during the middle period: a period practically defined by the drums of Tony Williams.

The ying is the composition. The figuring out how to compose songs that were springboards for the abstract modernism of what is sometimes referred to as Miles second great quintet (in fact there was no third great quintet).

1st Great Quintet

Miles – trumpet

John Coltrane – sax

Red Garland – piano

Paul Chambers – bass

Philly Joe Jones – drums

2nd Great Quintet

Miles – trumpet

Wayne Shorter – sax

Herbie Hancock – piano

Ron Carter – bass

Tony Williams – drums

There is no confusing the two quintets. Both sound magnifique but they have very little in common except the leader of each is Miles. Yet, even in that regard they are different. Even though immediately identifiable as Miles, the sound of his trumpet is different in each quintet. The first quintet emphasizes Miles’ lyrical minimalism, especially the steel-strong fragility of his muted work. The second period is aggressive; the horn sound is both fatter and faster—indeed, middle period Miles is the peak of Miles’ technique as a trumpeter.

* * *

In the ying of first period, the melody sings. Standards and hummable songs with easily recognized melodies, the solos are variations locked in a standard form.

In the yang of the second period, there often is no melody in the same sense. Sometimes it’s a vamp played over and over again, a single melodic line repeated with the variation in the rhythmic emphasis and rhythm patterns. Other times it’s totally abstract, a telepathic conversation about whatever. Whatever—no predetermined destination, no steady beat, no continuous anything; everything subject to change at the moment’s notice.

Which is not to say there were no compositions. Indeed, a number of modern jazz standards came from that band. (Both Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock were excellent and prolific composers.) Indeed, "Footprints," a Wayne Shorter composition first recorded by the second great quintet, is this week's cover feature. It is notable that both Shorter and Hancock recorded some of their most notable work outside of the Miles Davis quintet. Indeed, Hancock's Maiden Voyage album, often considered one of the masterpieces of modern jazz, is the Miles Davis quintet with Freddie Hubbard filling the trumpet spot, and despite using mostly the same musicians the album does not sound like Miles.

The Miles Davis personality determined the identity of the music but the musicians also had their own identities. Middle period Miles is Miles' most balanced period and arguably his most influential, although not necessarily his most popular. Music from Miles' middle remains a major chunk of the jazz repretoire, much more so than music of the first and third period.

Go here to see/hear the second great quintet play in concert in Stockholm 1967. Whether you dig it is not the question; consider this a lesson in how to make music on the fly. Watch how the tempo shifts, the beats come and go, the horn players make little reference to what little melody there is. There is no pre-set cycle of chord changes. Instead there is a river run of emotional conversation between the instruments, especially the bass and drums.

“Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)” is all soloing. Some from the old school want to know where’s the melody, where are they going, what’s going on?

What is amazing is that both songs are from mainly the same band. (“Mademoiselle Mabry” was cut during a transition period. On the Filles De Kilimanjaro album Chick Corea replaces Herbie Hancock and Dave Holland replaces Ron Carter on two cuts, including “Mademoiselle Mabry.”) The two personel changes notwithstanding, when you listen to the album the unified vision is obvious.

The common element is that both songs are led and articulated by the drums as lead instrument. It’s way past amazing. On “Nefertiti” Tony starts off establishing the walking tempo but before the first cycle of the melody is played through, Tony has fractured the beat with percussive fills that interrupt the flow, and in interrupting, he paradoxically emphasizes the flow.

If you are not a drummer it’s hard to imagine just how radical Tony’s drumming is. Traditionally, the drummer keeps the beat. In this band, that time-keeping function is given over to the bass. Tony’s drums are a total improvisation based on ????? That’s the thing—Tony is not playing rhythms, he is actually using the drums as a melodic instrument, sounding out patterns.

Meanwhile the melodic instruments (trumpet/sax) are just playing the same melody over and over and over with only micro-inflections in timbre and rather than sounding in unison they play shadowing one another (the trumpet a bit in front of the sax). Hancock’s advanced harmonies on the piano are spare chords stabbed like an expert point guard dribbling (cross-overs, behind the backs, etc.).

What I really, really dig about middle period Miles is that the music is simultaneously random abstract and intellectually rigorous, both emotionally free and emotionally engaged. You have to know some shit to keep up with what they are doing, but they are doing it freely, not preconceiving, but rather improvising in the moment, like the aforementioned basketball players do when they go hard to the hoop, not knowing exactly what they are going to do but knowing they are going to make a basket some kind of way (to be determined as they go). I.e. they simultaneously run the race and create a unique path. To do this successfully requires an extremely high skill level. It requires a command of both theory and execution; a fine-tuned body and imagination up the ying/yang. In other words, you must see with the eyes closed. You are not creating based on what is, but rather on what you imagine could be.

Most drummers don’t even try to do what Tony Williams seemingly did with ease. I know. I was one of those drummers who used to sit listening over and over to Tony, and just shake my head and mutter: "What’s the use? I can never do that." Imagine, he was still a teenager doing what grown men who been playing for many years could not even conceive not to mention achieve!

Another ying/yang aspect is that “Nefertiti” has a cool sound while “Mademoiselle Mabry” is on fire. "Nefertiti" is smooth. "Mademoiselle Mabry" is jagged. You can hear it in the sound of the drums, the former moonlit oceanic flow on a tropical, idyllic tropical beach; the later a tsunami of beats crashing and dashing against a reef. And the real beauty is that one drummer could do both so well. He could roll smooth as butter, or rock hard full out solid as a red St. Joseph’s brick. (And New Orleanians know how hard a St. Joe’s is!).

On these recordings, Tony Williams has the perfect combination of Art Blakey’s unerring hard drive and Max Roach’s melodic embellishments, executed with a sixties sensibility. I suggest you listen to these two tracks at least one more time. I guarantee you, you’ve missed a lot, some of which you can only catch on a second, third or fourth listen. Tony Williams is so bad that it takes more than two ears to hear what he is doing!

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Quiet, intricate and quite beautiful

I barely know where to start with this one. Filles De Kilimanjaro is my all-time favorite jazz album. Nefertiti is probably in my Top Five. I know both of these tunes like the back of my hand, having heard them both over and over and over.

Let me start with "Filles De Kilimanjaro." In this week's Contemporary post, I mentioned that Mos Def and Vinia Mojica's "Climb" encapsulates everything I like about music. I could easily say the same about "Filles." Even the tone of the two records are similar. One is a hip-hop record; the other is a jazz tune. But to me, the vibe is the same. When I listen to the two songs, I feel the same things. Of course, "Filles" is both longer and more complex, as is jazz music's tendency. The only thing I can think of to compare this music to (other than equally beautiful music) is some gorgeous sort of abstract painting...or perhaps shifting sand dunes or something ephemeral like that.

On the subject of "Nefertiti," one reviewer likened it to "a series of time lapse photographs of a particularly beautiful scene, with light and color and shadows subtly, but continually changing, thus shifting the focus of one's eye - or, in this case, ear." Another review talks about how Miles and Shorter "shadow each other's line in a deliberately inexact manner, almost like a form of silkscreening." At a blog that attempts to list and discuss the Top 100 jazz recordings of all time, the reviewer talks about how Miles and Shorter's technique "becomes more unsettling as the piece proceeds [because] the trumpet and saxophone become progressively more out of phase."

This last comment goes to the heart of why I love this music so much. I dig pretty melodies as much as anyone else, but I hate the big, obvious chord changes and power ballads of pop radio. For me, music is a metaphor for life and I see life as a strange but wondrous adventure. The music I love most reflects that. Miles' middle-period music (particularly the music he recorded at the end of the period) subtly but convincingly turns convention on its ear. On "Nefertiti," Miles and Shorter upend the norm by turning a simple head-riff into an entire tune; meanwhile, Tony and Herbie solo throughout, further playing with convention because they, as the rhythm section, are supposed to be the ones playing "the same thing" over and over.

On "Filles," Miles and his band subvert convention not by doing the opposite of the norm, but by exaggerating the norm. Tony, Chick Corea and Dave Holland are "supposed" to play just the rhythm, but here, they take the norm to a wild extreme, playing the same rhythmic figure over and over and over, virtually unchanged, for sixteen minutes. When I hear something like that, it gives me a deep and substantial sense of well-being. "Filles" is an unconventional dialogue, that, for all its strangeness, is also wondrous. To put it another way, I feel like hive highly skilled musicians are letting me listen in on their quiet, intricate and quite beautiful conversation. Each time I hear it, I feel a little bit better about both myself the world around me.

—Mtume ya Salaam

P.S. One quick note. I agree with almost everything Kalamu said, but I have to diverge on a couple of points. He says: “'Nefertiti' has a cool sound while 'Mademoiselle Mabry' is on fire. 'Nefertiti' is smooth. 'Mademoiselle Mabry' is jagged." I'm not hearing that at all. "Mademoiselle Mabry" is one of the calmest, most peaceful pieces of music I've ever heard. I'm mystified as to how he hears it as fiery or jagged. Maybe he's focused hard on Tony's drumming. I don't know.

The other thing is, Kalamu seems to be going out of his way to downplay Miles' impact and influence on his own band. Yes, Herbie, Wayne and Tony (and Ron Carter and Chick Corea too) all went on to record classic material on their own. So did John Coltrane (ha-ha). But these are still Miles' records, done Miles' way. How else do you explain that "Filles De Kilimanjaro" has virtually the identical sound as the rest of the album it comes from even though the personnel is different? It's because Miles had a sound, an aural ethic, that he was striving for and, in truth, had acheived. Baba, I know you're a die-hard 'Trane man, but come on! Miles is the truth. Jazz is big enough for both of them.

Giving The Drummer Some

Two short responses.

1. I wrote the cool/hot analysis backwards: "Nefertiti" is the hot, "Mademoiselle" the cool. It has to do with Miles constant swing back and forth over the course of his career in terms of his approach to making music. Note that all of the music on Filles was composed by Miles. "Nefertiti" is a Wayne composition. At the height of the middle period most of the compositions were by the band members not Miles. And that brings me to the second point.

2. No doubt about it Miles was perhaps the greatest band leader in modern jazz, certain the greatest after Blakey, who took the tittle from Dizzy. I'm not just thinking of musicians as players but also the compositions that came out of a particular band. Few people play the music from third period Miles, most jazz musicians still play music from middle period Miles and most of those compositions are not Miles Davis compositions; usually the composer is either Wayne or Herbie in terms of music from that period that is still being played.

My intention was not to slight Miles but rather to give props to the band members, props that are usually layed at Miles' feet because he was the leader but that band was a collective of players and composers who created one of the greatest stretches of recorded jazz.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Monday, May 26th, 2008 at 12:10 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |