ABDULLAH IBRAHIM / “Mannenberg Is Where It’s Happening”

PREAMBLE: Regardless of the length of what I’ve posted over the last year or so, I’ve made a conscious effort to write a lot less than I know and feel, but at the same time not to short change our readers or insult their intelligence by dumbing down to a bare outline or only a few of the essentials. Rather my effort has been to develop a stylistic device to make the work stronger—the old 'less is more' theory. In literary circles, it’s sometimes called the iceberg theory: show the tip, imply what lies below the waterline. But sometimes we are dealing with more than a mere iceberg and the subject is both so important and so complex that there is no easy way to even hint at the complexity or the immensity of the substance not seen. Writing about Abdullah Ibrahim’s “Mannenberg” is one such occasion. So I apologize in advance for taking a long way around, however I saw no other way. “Mannenberg” is one the single most important productions in the long and glorious history of jazz. Here is the evidence in as condensed a version as I could manage.

Upon its release in 1974 as one of two long cuts on the album Mannenberg Is Where It’s Happening, the people of South Africa embraced the song and made it anthem of their struggle. In 1974 and 1975 the record sold more than any other jazz album in South Africa. Ironically, none of the South African record companies wanted to put out the recording. Composer Ibrahim and recording engineer Rashid Vally ended up self-promoting the initial release and then, after selling 5,000 copies in one week, they licensed the music to Gallo Records, South Africa’s largest record company. Gallo sold over 40,000 copies in less than a year. At that time in South Africa sales of 20,000 was a certified hit for any type of music.

Upon its release in 1974 as one of two long cuts on the album Mannenberg Is Where It’s Happening, the people of South Africa embraced the song and made it anthem of their struggle. In 1974 and 1975 the record sold more than any other jazz album in South Africa. Ironically, none of the South African record companies wanted to put out the recording. Composer Ibrahim and recording engineer Rashid Vally ended up self-promoting the initial release and then, after selling 5,000 copies in one week, they licensed the music to Gallo Records, South Africa’s largest record company. Gallo sold over 40,000 copies in less than a year. At that time in South Africa sales of 20,000 was a certified hit for any type of music.

"So now we’re in Johannesburg, nobody wants it [Mannenberg]. Rashid [Vally] has this little record shop… So I say to Rashid, ’Why don’t we just make demos and put loudspeakers outside and play them?’ We sold 10,000 over the counter without covers. We sold 10,000 in two weeks, without covers - it was incredible!" — Abdullah Ibrahim, in an interview with Sue Valentine, on how they managed to sell MannenbergWhy was the record so beloved? What, if anything, was different about the sound? Who had made it and how did it come about? And what or where was Mannenberg? Today the song may sound like a pleasant, happy jazz tune that would fit into the club scene. In June 1974 Black people were dancing alright, dancing in the street fighting apartheid. The song is named for a suburban area of Cape Town, South Africa. The Cape Flats township was spelled with two “n’s” (Manenberg) but when the album was released they used three n’s in the name.

BITTERNESS AND VIGOROUS PROTEST Mannenberg the song aroused a gut reaction among Capetonians at the time as it "spoke" eloquently of the forced removals of black people out of District Six and into the bleak and distant new racially explicit "group areas" like Manenberg. Here Jennifer Hayman reports on the plans to remove people from District Six."Most of District Six’s inhabitants have already been moved under the Group Areas Act. The remaining few thousand families watch with resignation and a fair amount of bitterness as their centuries-old homes are demolished… Overriding vigorous protests from residents themselves and from concerned Whites all over the country, the Department [of Community Development] began purchasing properties in District Six and by 1970 had paid nearly R14-million for them… Some 30,000 Coloureds and Indians were to be moved by the mid-70s to make way for 15,000 Whites in ’luxury or semi-luxury high-rise flats and maisonettes’." — Rand Daily Mail, May 25, 1974 [Wits Historical Papers: Removals — Western Cape, 1952-1975 (Box 217.4)] Of course, the people resisted. Both court cases and street battles raged. "Mannenberg" became a battle cry of resistance. Here was a record that consciously championed the people’s cause. That’s Abdullah shouting out at the end of the record. Say it loud…!

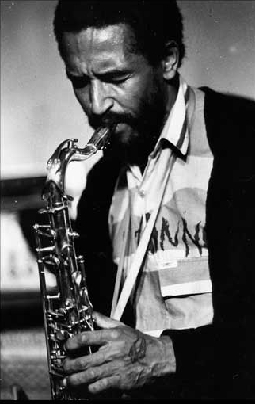

Morris Goldberg

It was common sense to join the majority in opposing minority white apartheid policies but it was also radical to join together under the banner of blackness and eventually to turn to ubuntu (humanness). Ubuntu was a ways off back then. The black struggle had arrived in full force and “Mannenberg" was an affirmation of and identification with full out blackness—and remember that one of the “Mannenberg” musicians, Morris Goldberg, was white. It was not about race per se, but rather about consciousness.

Morris Goldberg

It was common sense to join the majority in opposing minority white apartheid policies but it was also radical to join together under the banner of blackness and eventually to turn to ubuntu (humanness). Ubuntu was a ways off back then. The black struggle had arrived in full force and “Mannenberg" was an affirmation of and identification with full out blackness—and remember that one of the “Mannenberg” musicians, Morris Goldberg, was white. It was not about race per se, but rather about consciousness.

And speaking of names, when the album first came out the leader was listed as Dollar Brand (which was the name Aldolphes Johannos Brand went by). When he converted to Islam, Brand took the name Abdullah Ibrahim.

"In 1974 he [Basil Coetzee] joined up with his musical guru, fellow jazz great Dollar Brand (as Abdullah Ibrahim was then known) and collaborated as one of the saxophonists on the album Mannenberg — Where it’s happening. The hauntingly beautiful instrumental song lasts 11 minutes and is widely regarded as the "anthem of the revolution". It is from this venture that Coetzee got the name Mannenberg. — "Coetzee, anthem of the revolution", Cape Times, March 13, 1998 "It seems like just yesterday that I first heard that riff… that special sound that helped build that wider family during a time of deep repression, when speech was not enough. That sound which is something we can feel but not explain, which gave voice to the speechlessness of those times." — Minister of Finance Trevor Manuel (then a leading figure in the UDF), speaking at the funeral of Coetzee. From: A Struggle Biography "Abdullah [Ibrahim] tells a remarkable story about two tunes that he performed in Cape Town in 1976. These became the anthems of children in the streets of the city. They were the tunes Mannenberg (named after a township in Cape Town that is parallel in significance to Soweto in Johannesburg) and Soweto. The saxophone solos were being sung to words all over the country, as anthems of anger and resistance to the apartheid regime. Just a few months after the recordings of these tunes were released, the Soweto uprising occurred. This was the turning point in South African history, when the South African security forces gunned down schoolchildren, who were protesting against [Afrikaans] language instruction in schools." — Muller, Carol Ann, "Capturing the ’Spirit of Africa’ in the Jazz Singing of South Africa-born Sathima Bea Benjamin", in Research in African Literatures, Vol. 32, Number 2, Summer 2001, p142

—THE POWER TO UPLIFT

"I [Abdullah Ibrahim] used to use very eloquent language. Then I realised that hardly anyone understood what I said. It was only when I met Basil Coetzee (tenor sax), Robbie Jansen (alto sax), Paul Michaels (bass) and Monty Weber (drums) that I finally found jazz musicians prepared to play traditionally based music — and that’s how Mannenberg finally got through." — "Reunion", Leadership, October 1990 —THE MEN BEHIND THE MUSIC

* * *

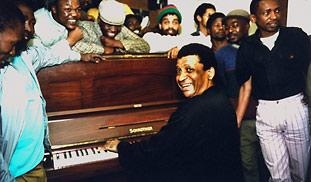

AI: …I thought, "Great, an old upright piano", I touched this piano, and I thought, "What?" This is what they did in the old days, they take an upright piano, put tacks on the hammers, that’s what the marabi players used to do with the harmonium. You take a match stick and set up your tone role; you want to hit an F, you put a matchstick in there, it holds it down; you hit a C and it drones on in the background, you can do your thing on top of it. I sat at this piano and it goes [sings out opening notes of Mannenberg], first time. Wow! This thing sounds so nice, it’s grooving. I tell my musicians that I work with a lot of music that is written right there. So they bring pens and pencils and paper. I’m a composer; you don’t know when it’s going to happen. So this is how Mannenberg was written. OK, now we have a bridge; OK, let’s go. SV: So it was as you sat down at that piano that you developed that refrain? AI: Yeah. SV: So all that rehearsing beforehand? AI: It was all gone. [laughs] All the stuff we had rehearsed, when we went back to it, it sounded so flat. SV: So it was as much the sound of the piano that inspired you as other things? AI: The sound of the piano. Also the upright piano, because I grew up playing upright pianos. And the sound of it, it just transported me. They used to call it "diepa", the equivalent of the house-rent party, with the boogie-woogie piano, but they called it "diepa" it was like African stride, you know. You’d go all over, like Kensington here in [Cape] town; you’d go all over the country you’d hear it, stride piano. It came out of Kimberley, because with the discovery of diamonds there was a lot of ragtime… SV: All the musicians who pulled in there? AI: Mining towns and ragtime. And they incorporated it. They would start like Friday night and it ends Monday morning. [laughs] "Diepa", it was just piano and people dancing and there was a table with a plate. And you would say, "A shilling and I want this song". And another one would say, "No, two shillings I want that song". And it was a house-rent party, to pay the rent. They had the same thing, that’s where all the pianists got together. SV: And so when you hit on that melody, how much did you develop that melody? Because I suspect there are a lot of urban legends about this song, Basil picked up on it [Ibrahim nods] and between the two of you… AI: Because they were all standing there, they couldn’t figure what was going on. But Basil was attuned to this because he’d started off playing pennywhistle; he was locked in to the tradition. And then of course, I’d had the experience of playing dance bands, African dance bands like the Tuxedo Slickers, and we played Xhosa, American swing music, mbaqanga. On the other hand, I also played with coloured dance bands: waltzes, quick steps, squares, pasa double, then also the traditional Cape music. The songs my grandmother used to sing, the songs I heard around her, Daar kom die Alibama, a confederate ship. When I went to Malaysia and Indonesia, I went to visit the Batavia, the ship that was coming from them. Also, Sheikh Yusuf, the Kramat, he was from Macassar, that’s why the beach is called Macassar. And of course, he’s not there because the body was taken back to Indonesia… so, all these linkages… [Sings/hums] "’n Man van Sofia... na Batavia, na Batavia". That was a Nag Troep. You know the difference between the Klopse and the Nag Troep and the Christmas choir? SV: What’s the difference between them? AI: Christmas choir are people who are very sociable, smart dressers, suits, hats, the play violins, they play Christmas hymns on Christmas and Easter. The Klopse are coons and the Nag Troep are Malay. Now there was a Christmas Choir with only Malays in and the people of District Six would say, "Hier kom die Slaamse Christmas Choir!" You know, Slaamse, the Muslims … [laughs] … So from an early age, even now, there are so many things I’ve discovered, just driving around here … When we recorded this song, Mannenberg, when it came and we just played, we just played. Normally they will tell you, you must have stated airtime three or four minutes, I just said, "let it ride, let it ride", it felt so good… Now we went back to the other stuff, but the stuff sounded flat, so I said "Vic, [the recording engineer] can you play this back again?" Then we realised something had happened then, and it was actually the mood. I’ve written stuff like that, but to be in the studio and have it recorded, that was the first time that it ever happened. And of course, Vic was very receptive to the music — that was very important. I mean the recording studio is only as good as the engineer. He also realised what was happening. So we finished the song and we listened to it over and over again, so he said, "What is this song?" We said, "Mannenberg". He said, "What?" I said, "Mannenberg — it’s happening in Manenberg [sic] right now". People were being shot down all over. SV: Why Manenberg as opposed to anywhere else on the Cape Flats? AI: Because Basil was from Manenberg and for us Manenberg was just symbolic of the removal out of District Six, which is actually the removal of everybody from everywhere in the world, and Manenberg specifically because… it signifies, it’s our music, and it’s our culture … And of course when the thing was released, when we listened to it, we said, "OK, it has the combination of everything in it." If you listen to Monty, [makes drum sounds] which is actually this Cape beat. Now in Johannesburg they used to call it tiekiedraai, which is almost derogatory, and in Cape Town they used to call it kaffirmusiek, but now if you listen to pantsula, it’s the same thing. And then, technically also, when I try to work out what has happened, the chords and the melody line, it was quite something, from a technical perspective, which I won’t bore you with … Of course when we recorded it, we took it to all the record companies and nobody wanted it. Nobody wanted it. We walked. And the musicians, before we went into the studio, I said, "Why don’t we start a co-operative? Why don’t we create a corporation? We’ve got this band together, we’re all in need of daily requirements, we don’t take any money, we form a corporation, then we share the income, then we get our families and we buy food in bulk. Nah [they said], just pay us for the gig!" OK, so now sitting with this, Rashid, we go to the record companies, nobody wants this. I say Manenberg — I asked the photographers, the graphics people, "Can you create something?" They came up with rubbish, so I just took a camera to Manenberg and took a photograph. SV: That picture of the woman with the doek?AI: That’s my photograph! Because I studied photography and film-making. So now we’re in Johannesburg, nobody wants it. Rashid has this little record shop… So I say to Rashid, "Why don’t we just make demos and put loudspeakers outside and play them?" We sold 10 000 over the counter without covers. [laughs] We sold 10 000 in two weeks, without covers, it was incredible! And the stories… There was, you know, at Diagonal Street, the bus terminus, there were these two guys, they commute every day — the one is blind, the one is disabled. So the disabled [guy] meets the blind [guy] and every day they come to town, and they never came into the shop. [One day], they walked past the shop and the music was playing. They stopped, they asked, "What is that?" so Rashid told them, and they said, "OK." The next morning when Rashid opened the shop they were there with the money, they were there with the money to buy the record. There are so many stories about it. In exile, MK [Mkhonto we Sizwe] used to say to me they used to play this stuff on Christmas eve, New Year’s eve in the camps. When I was invited by the late Johnny Makatini, who was the [ANC] foreign minister in exile, and also by the late Oliver Tambo, we went to the [ANC] school [in Tanzania], there also we found this music, and of course it became almost like a signature tune, an anthem. "I WRITE WHAT I KNOW BEST"

* * *

Now here is where the story gets deeper than deep: y'all know my hole in the ground theory? Well here comes theory number two: the black bee theory—worldwide Black culture advances on the local level through cross pollination via the international scene. That’s right: every major local development whether on the continent or in the diaspora, every major "local" development had some international element embedded. “Mannenberg” is a prime example. My short cut is to give you a long quote from “Mannenberg”: Notes on the Making of an Icon and Anthem by John Edward Mason and published in Volume 9, Issue 4, Fall 2007 of African Studies Quarterly, The Online Journal for African Studies.Robbie Jansen

First emerging in the late 1960s, Black Consciousness had changed the political climate within portions of the coloured community, especially the better educated youth. Drawing in part on African-American Black Power slogans and ideology, activists within the Black Consciousness movement believed that their “primary task” “was to ‘conscientize’ black people, which meant giving them a sense of pride or belief in their own strength and worthiness.”[101] Among other things, this involved asserting the value, dignity, and beauty of indigenous and working-class black cultures.[102] Because Black Consciousness redefined “black” to include coloureds and South Africans of Indian descent, as well as Africans, an identification with blackness encouraged coloureds to reappraise of those aspects of their culture which had formerly seemed to be retrograde and shameful. But it is easy to over-estimate the impact of Black Consciousness.[103] Robbie Jansen, for instance, knew hardly any advocates of Black Consciousness. The few he met were university students, part of a tiny minority of coloured youth who went beyond secondary school. But Jansen did accept that to be coloured was to be black, part of an oppressed community engaged in struggle for freedom. And he believed that black was beautiful. It was, he said, “the American influence,” the influence of African-American popular culture.[104] The music, clothing, and hair styles of black America taught Jansen and young coloured people of his generation that “it was the in thing to be black, and people started to be proud of being black.”[105] This was hardly the first time that coloured people had looked to the United States for models of blackness. After all, this is precisely what Ibrahim and “the hipster breakaway” had done. Many coloured people knew that similar histories of slavery, oppression, cultural assimilation, and permanent minority status within white supremacist nations linked them to the African-American experience. While coloureds were drawn to black Americans, there were forces within South African culture which pushed them away from Africans. Rashid Lombard saw how the “divide and rule” strategy of the apartheid state had been “so effective” that a chasm of distrust and suspicion separated the coloured and African communities. The road to blackness, for him and his friends, was smoother through Harlem than through Gugulethu, the African township just on the other side of the tracks from Manenberg.[106] Consider the “Afro.” By the late 1960s, this hairstyle, also called the “natural,” had become the emblem of black pride, the new black American assertiveness associated with Black Power. African-Americans, young and old, male and female, grew their hair long, emphasizing its tight, African curls. It was a reversal of earlier attitudes that defined “good hair” as straight, “white-looking” hair and “bad hair” as kinky, “black-looking” hair. Millions of African-Americans, from political figures, such as Angela Davis and Huey Newton, to cultural heroes, such as Sly Stone and Michael Jackson, to ordinary men and women and boys and girls adopted the style.[107] By the mid-1970s, the Afro had come to coloured Cape Town. So many coloured people were wearing Afros that even the Herald, that most politically timid of newspapers, felt free to sponsor an “Afros for Africa” contest. It offered advice on how to grow and care for a good looking Afro and published the photos of the entrants.[108] The scores of coloured teenagers and young adults who entered were radicals, in their way. They had turned the politics of hair upside down. Most coloured people, up to this point, had gloried in their straight hair, if they had it, and desired it, if they didn’t. Now, for the first time, hair that was associated with blackness was desirable. For many, the Afro was the “sign and symbol” of a new identification as “black.”[109] Afro had come to Cape Town by way of African-American popular culture, especially soul music. Newspapers, magazines, and album covers all depicted black American soul musicians wearing their hair “natural.” Responding to reader interest, the Herald had, since the late 1960s, profiled soul performers and promoted their music. It even acknowledged the politics of soul, explaining that its roots lay in the “suffering” of the African-American people and declaring that “The Sound is Black and Very Beautiful.”[110] As Brian Ward has convincingly argues, the “actual sound and texture” of soul music, its deep embrace of the African-American musical tradition and its disregard for white American traditions, carried a message of black pride.[111] Cultural aspects of African-American blackness, such as music and hair styles, provided a safe passage to blackness for coloured South Africans, instilling within them a sense of pride and allowing them to see themselves as beautiful, without having, necessarily, to move physically or psychologically closer to African South Africans. Changing political and cultural trends prepared the coloured community for “Mannenberg.” It presented coloured listeners with a sound that resonated deeply with their history and experience and yet was utterly contemporary. Much about the song, especially its sensibility and the very sound of the saxophones, was uniquely and recognizably coloured. What had begun as an improvisation in a recording studio became a community icon. Instead of Ibrahim’s portrait of a lady, the community had made it a portrait of themselves.

Once one understands the full import of “Mannenberg,” it’s staggering. Issues of the individual development of artists, the relationship of the artist to the community, the function of commerce in the production and distribution of art, the question of aesthetic development either divorced from or wedded to broader political struggles, and a host of other issues are all highlighted by this one song.

“Mannenberg” could be a graduate level college course just by itself. Or conversely, it could be a song played for and taught to grade school youngsters to help them soulfully appreciate their culture and history.

Obviously there is a lot more to be said but I’m going to stop… or, I should say “pause” right here. Pause, because I plan to do a feature on Abdullah. Soon. I promise.

Yeah, yeah, I know. I said the same thing about Milton Nascimento, and Pharoah Sanders, and some other stuff. I mean, well, you know, we do as much as we can in the time that we have, and… well, as long as we’re living, we’ll keep doing it and that’s the best we can do.

A lot of music critics think it’s about aesthetics, about how the notes are put together. But ultimately it ain’t. It’s about the people. To understand the music, understand the people. To understand what’s going on with the music, understand what’s going on with… You got it. More to come. Stay tuned.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

I can feel it

I've never heard "Mannenberg Is Where It's Happening" until this week and yes, it does sound like a happy jazz tune. I even commented to Beth that it's hard to believe that such a pleasant-sounding record could've gotten people fired up enough to serve as an anti-apartheid anthem. At the same time though, there's a strong spirituality at the core of the record. It's not on the surface, but it's definitely in there. I can hear it. I can feel it.

And how interesting is it that Ibrahim credits the unique sound of the record to not just himself and other musicians who were there and who knew and loved the old traditions but also to the actual old piano that was there? It was as if that standup piano was the conduit that led them from were they were - ready to play some new and hopefully hip music - to where they ended up, which was older, more soulful and definitely, defiantly hipper than anything they could've come up with otherwise. Funny how an inanimate object can be just as central to the birth of a recording as is the composer or musicians.

Of course, I'm also not trying to minimize what the musicians and Ibrahim actually did or the composite of lifelong musical knowledge they had to have to come up with their thing. Somewhere in the write-up there was this quote from Ibrahim: "And then, technically also, when I try to work out what has happened, the chords and the melody line, it was quite something, from a technical perspective, which I won’t bore you with." Which says to me there's a lot more to this record than the peaceful, swinging lilt of its surface.

Also, I have to say, this is been a truly eye-opening week. It really doesn't matter how much you know (or think you know) about the music, there's always more to learn. Always. Just speaking as a student of the music, this has been the deepest week at BoL in quite a while. And I'm definitely looking forward to that Dollar Brand/Abdullah Ibrahim feature. I'll make it a point to pester Kalamu until he does it. ;-)

—Mtume ya Salaam

Once one understands the full import of “Mannenberg,” it’s staggering. Issues of the individual development of artists, the relationship of the artist to the community, the function of commerce in the production and distribution of art, the question of aesthetic development either divorced from or wedded to broader political struggles, and a host of other issues are all highlighted by this one song.

“Mannenberg” could be a graduate level college course just by itself. Or conversely, it could be a song played for and taught to grade school youngsters to help them soulfully appreciate their culture and history.

Obviously there is a lot more to be said but I’m going to stop… or, I should say “pause” right here. Pause, because I plan to do a feature on Abdullah. Soon. I promise.

Yeah, yeah, I know. I said the same thing about Milton Nascimento, and Pharoah Sanders, and some other stuff. I mean, well, you know, we do as much as we can in the time that we have, and… well, as long as we’re living, we’ll keep doing it and that’s the best we can do.

A lot of music critics think it’s about aesthetics, about how the notes are put together. But ultimately it ain’t. It’s about the people. To understand the music, understand the people. To understand what’s going on with the music, understand what’s going on with… You got it. More to come. Stay tuned.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

I can feel it

I've never heard "Mannenberg Is Where It's Happening" until this week and yes, it does sound like a happy jazz tune. I even commented to Beth that it's hard to believe that such a pleasant-sounding record could've gotten people fired up enough to serve as an anti-apartheid anthem. At the same time though, there's a strong spirituality at the core of the record. It's not on the surface, but it's definitely in there. I can hear it. I can feel it.

And how interesting is it that Ibrahim credits the unique sound of the record to not just himself and other musicians who were there and who knew and loved the old traditions but also to the actual old piano that was there? It was as if that standup piano was the conduit that led them from were they were - ready to play some new and hopefully hip music - to where they ended up, which was older, more soulful and definitely, defiantly hipper than anything they could've come up with otherwise. Funny how an inanimate object can be just as central to the birth of a recording as is the composer or musicians.

Of course, I'm also not trying to minimize what the musicians and Ibrahim actually did or the composite of lifelong musical knowledge they had to have to come up with their thing. Somewhere in the write-up there was this quote from Ibrahim: "And then, technically also, when I try to work out what has happened, the chords and the melody line, it was quite something, from a technical perspective, which I won’t bore you with." Which says to me there's a lot more to this record than the peaceful, swinging lilt of its surface.

Also, I have to say, this is been a truly eye-opening week. It really doesn't matter how much you know (or think you know) about the music, there's always more to learn. Always. Just speaking as a student of the music, this has been the deepest week at BoL in quite a while. And I'm definitely looking forward to that Dollar Brand/Abdullah Ibrahim feature. I'll make it a point to pester Kalamu until he does it. ;-)

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Monday, March 17th, 2008 at 12:41 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

4 Responses to “ABDULLAH IBRAHIM / “Mannenberg Is Where It’s Happening””

March 20th, 2008 at 4:48 pm

thanks for the background, kalamu, fascinating reading. abdullah toured here (australia) with a trio a few years back. he played an open air festival for the WOMAD organization. it was a beautiful afternoon and his free-flowing, warm and enegaging music was increadibly uplifting. it is wonderful to be able to read more about his background

April 12th, 2014 at 4:52 am

Incredible articule, thank you so much. I come from Spain and discovered this song through the Robbie Jansen and the Sons of the Table Mountain years ago, could not stop listening to it every sunday as other go to church, That was the iceberg tip for me to dig and dig down to Cape Town jazz festivals and reaching the source of Mr. Ibrahim recording track of Mannenberg (a Mountain of men), from Hilton Shilder to Dollar Brand, from Robbie Jansen alto to Basil Coetzee Tenor, as if the music had spoken its universal language because only later I discovered the profound meaning of the song for a whole nation yearning for peace and freedom.

Thanx for sharing,

Greetings from Madrid.

Amandla

June 11th, 2015 at 6:35 am

Good to read the background to Thai song I used to listen to I. The 70’s in Melbourne, Australia with African international students. Had the delight to hear the dulcet tones of Ibrahim’s piano this year when he came down under!

September 4th, 2015 at 4:41 am

Thank you for the history. It’s wonderful to be able to immerse myself in reading about Mannenberg as well as listening to it as often as I do. I bought Voices of Africa a few years ago and listened occasionally. Since last year I’ve been playing it daily sometimes on repeat. My favourites are Mannenberg and The Pilgrim. I wanted to know more about Mannenberg when I found myself singing this tune to myself on my way too work or just randomly. This has brought me to your site and the fantastic review and interview with Abdullah Ibrahim. The opening thunderclap on the first track is symbolic of the album as a whole – releasing, enlivening, soothing, and above all a meditation. Give Thanks.

Leave a Reply

| top |