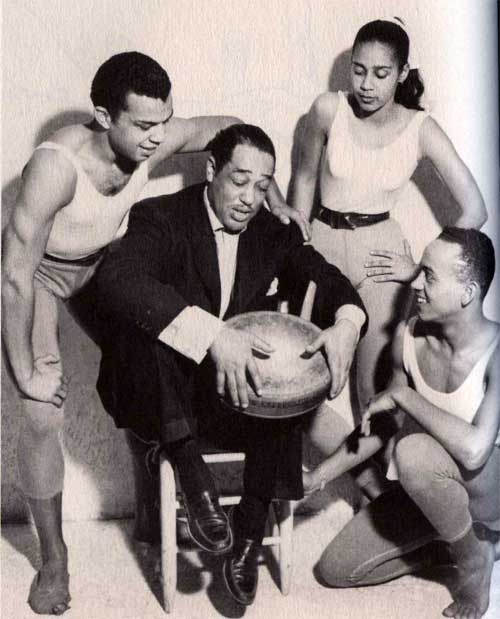

DUKE ELLINGTON / “Ballet of the Flying Saucers”

A Drum Is A Woman is classic Duke Ellington.

It’s an anomalous classic. Although listed under Duke Ellington’s name, the suite was actually co-composed in 1956 by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, which was in fact the norm for these two iconic collaborators. Duke’s music has been celebrated, issued, reissued, repackaged, remastered, anthologized, compiled, boxed and broadcast for close to a century. Both commercial and private recordings have been issued, radio broadcasts and movie scores are widely available yet somehow this historic music is out of print. Other than the Columbia LPs there has been only one brief and limited CD release, a French import on the TriStar label. I do not know why it is no longer commercially available but the whole album is in this week’s jukebox.

On May 8, 1957 A Drum Is A Woman was presented as Episode 18, Season 4 of the nationally televised U.S. Steel Hour series.

The dance suite featured Carmen Delavallade as Madam Zajj, the personification of jazz. Consider the context: no Malcolm, no King on the scene yet; three years after Brown vs. The Board of Education, seven years before the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The only black a person usually saw on television was when you turned the set off. So here comes supremely confident, hip, urbane, witty Duke Ellington and his Orchestra composing what is essentially a combination ballet, opera, historical panorama that wildly conflates jazz into the trope of a woman who is also a drum, muse and heartbeat, sex and creation.

Eschewing the obvious and the earnest, Duke and Strayhorn crafted a marvelously droll musical pageant. That Ellington chose dance as the vehicle harkens back to his Cotton Club days, back to his ability to compose jazz that was both serious and danceable. Although never thought of as a “militant” during the Civil Rights and Black Power eras, Duke had a deep love for and philosophical appreciation of black culture. Although black music’s importance may seem obvious today, in the middle of the 20th century, black cultural productions were seldom recognized as art forms and at best were generally considered entertainment.

Duke was different from the conventions of his and our time. Duke had deep insights into the origins and artistic importance of his culture, thus his understanding of the conjoined nature of dance and jazz. No one else before or since has even attempted so successful an artistic piece that combines dance, music, lyrics and narration to present a popular history of jazz.

Most of Duke’s music focused on the instrumental but A Drum Is A Woman has more narration and song than instrumental passages. Duke’s distinctive delivery is a delight throughout, redolent with a raconteur’s mastery of articulation and enunciation made even more masterful by Duke’s cool, non-aggressive hipster delivery.

Featured vocalists are Margaret Tynes, Joya Sherrill, and Ozzie Bailey. Featured instrumentalists are Clark Terry on trumpet, Sam Woodyard on drums, Jimmy Hamilton on clarinet, Johnny Hodges on alto, Paul Gonsalves on tenor, Ray Nance on violin and Candido on percussion.

The varied musical interludes are wonderful tone portraits that succinctly capture the feel and style of various genres, styles and eras of black music. Individually, none of the selections are overwhelming but taken collectively this is a remarkable achievement. I love the clarinet interludes on the New Orleans sections, Clark Terry's channeling of Buddy Bolden, Ray Nance's subtle violin obbligatos, the sensitive use of harp riffs and the highlighting of bebop which captures both the hip humor and the virtuosic seriousness of that post-war music, not to mention Candido's brilliant conga solo or Woodyard's power drum solo. Like a resplendent crown, A Drum Is A Woman is encrusted (to borrow Duke's word) with musical gems.

Many critics were contemptuous of Duke’s effort. Some felt Duke was being pompous and ascribing far more weight to jazz than the music could successfully carry. Some diehard Duke fans were put off by the storyline, which they considered naïve, others felt there was not enough music and too much talking. So forth and so on.

In typical Duke fashion rather than become angry, frustrated or offended, Mr. Ellington wryly countered: “They think that Louis Armstrong should always have his handkerchief and Cab Calloway should always sing hi-de-ho, and the minute they do anything new, they’re out of character. They think that nobody grows up, everybody stays a child.”

Ellington’s music was more than child’s play, more than entertainment. Even when the music lost its playfulness, it never stopped being entertaining. The secret was, as Ellington noted, the music could contain everything: old and new, gutbucket to concert, world influences to “primitive” rhythms and plangent blues. One did not have to choose or exclude, everything was not only permissible but indeed jazz masters encouraged by example that we should try everything, reach for all that we can possibly achieve—and we can not possibly know how far we can go until and unless we leave where we are. We can not reach our limits until we go beyond the boundaries.

I love A Drum Is A Woman because it dares so deeply to be the totality of what jazz was at the time it was written: from Joe in the jungle to Madam Zajj in a diamond-encrusted hothouse on the moon!

The cover of the LP features a white woman in red viewed from the rear as she sits on a drum (accentuating the shape of her derriere), her arms upraised. Zajj was not a white woman even though the conventions of the time period forced that presentation.

The picture on the cover notwithstanding, I knew instinctively that this recording was a praise song not only for jazz but also for black women. I liked that.

On a personal level A Drum Is A Woman was the first jazz record I loved. My father used to play it every Mardi Gras day. It was part of ritual celebration in our house. Soon I could recite along with Duke, especially that wild stoplight scene: “Keep the change officer cause I’ll be back just as fast as I’m going.” To my adolescent ears the zany monologues were both funny and beautiful. I’m sixty now and more than ever I profoundly appreciate the wit and wonderfulness of Duke’s exquisite music.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

I'm split on this one

I'm split on this one. On the one hand, the music—both the infrequent instrumental passages and the accompaniment to the vocal and choral pieces—is impeccable. Listening to this album, I finally understand the frequent criticism of some of Wynton Marsalis' later work as a lesser version of Duke's compositions. Musically, I really enjoyed this album.

The lyrics? I don't know. There's the thing about ol' boy discovering that his woman has turned into a drum. What does he do then? He beats her, of course, because "what else can you do with a drum." Hmm. I know it's a metaphor but still it's a weird and unsettling metaphor, particularly given the celebratory and casual way they repeat it over and over.

Then there's the thing about the primitivism of rhythm and drums...and jazz too, I guess, if we are supposed to consider Madame Zajj the metaphorical embodiment of jazz. Duke uses adjectives like gaudy and flashy and exciting. He talks about men being helplessly drawn to the physical allure of the primitive. I know '56 was a different time. I know it was pre-Civil Rights era, let alone Black Power era. But even taking into account that this record was made in the '50s, am I the only one who finds those descriptions disturbing? Sometimes, Duke and Strayhorn sound like they're calling drumming and rhythm, and by extension black people themselves, savage. I don't dig any of that.

I do like some of the narration though. The bit Kalamu quoted is very funny. I also like the description of Mardi Gras morning in New Orleans:

The Mississippi river looks like a puddle of pecan-blue pudding — pistachio and indigo. And the sun, a neon-rose lollipop, is being drawn up over the horizon into a fizzy bunch of grape-colored clouds.

That's pretty. And like I said, from the music to (some of) the narration, there's a lot to like about this album. In the end though, it's hard for me to enjoy listening to sweetly-worded poems about beating women and the savagery of rhythm.

—Mtume ya Salaam

I Hear You

...and I totally agree about the negativity of "beating" women.

I don't read the savagery of rhythm in the same way. I'm not ashamed or embarassed about it.

What I'd really like to focus on is Duke who was not only noted as a "lady's man" but who was also a person who abhored violence and aggresiveness. Additionally, Duke Ellington was sophisticated and some considered his music too "learned" for jazz, to full of European classical influences. When Duke embraces the savagery of rhythm I hardly think he means it in a demeaning, ignorant or socially negative manner. Finally, I think Duke was realistic in his depiction of specific aspects of our culture. We was, is and always will be (shall we use the term) "colorful," ostentaciously so, unashamedly so.

Oh, one other thing. I think much of what Duke describes as well as the aspects you criticize remain a major part of our musical culture. I think we should change some aspects but I can't deny that Duke was telling the truth about us, even if it is an uncomfortable truth.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Monday, January 14th, 2008 at 1:11 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |