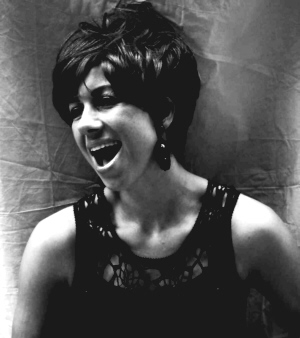

ARETHA FRANKLIN / “Skylark (Alternate Version)”

It was March, 1965. Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee. That’s where I first heard Aretha—I mean really heard (as in recognized the sound of greatness and consciously remembered her voice; marked off Aretha song as another notch on my inner coordinates of musical beauty).

The song, if my memory serves, was “Lee Cross,” although equally plausible, it might have been “Running Out Of Fools.” Both were pointing to where Aretha was going but had not yet arrived: a long ways away from the fifties. When Aretha signed to Columbia in 1960, producer John Hammond initially was trying to recreate Dinah Washington’s pop success, a success that was essentially an appeal to the mainstream market (i.e. middle class whites). Even though Dinah was a great jazz and blues singer, her commercial success as a pop artist is the mold in which Columbia wanted to squeeze Aretha.

During the sixties even a cursory glance will enable one to easily chart the movement of black musicians from straight up assimilation and entertainment to defiant embracing of ethnic pride and tacit purveying of coded messages of upliftment and encouragement. The Queen In Waiting (The Columbia Years (1960 – 1965) is more than a collection of early Aretha Franklin; the double-CD set is an incisive and insightful documenting of a major record company trying to push for musical stasis against an emerging voice that was willfully headed deep into the heart of then emerging blackness.

Uniformly the arrangements are either saccharine verging on schmaltzy—dripping with strings, vocal chorus, and muted horns—or else we’re subjected to tuxedoed R&B, the fire of the funk dampened down to a simmer. There is neither the full out consciousness of jazz nor the buoyant spirit of raucous R&B, not to mention precious little of the emotional catharsis of gospel. Fortunately, Aretha’s magnificent voice could not be kept in the kitchen preparing meatloaf, mash potatoes, succotash with apple strudel for dessert.

Notably there are no originals by Aretha in this collection. She's interpreting other people's music. She ranges from a direct hommage to Ray Charles during which she literally calls his name ("Hard Times") and a hommage to Dinah Washington ("Nobody Knows The Way I feel This Morning") to covers of standards ("Skylark") and even a cover of Dionne Warwick ("Walk On by"). Columbia tried a little bit of everything but was never able to come up with a market success.

If you listen to the two versions of “Skylark” you can clearly hear what’s up. On the short version, which was initially released, Aretha has to fight her way through the strings. She sticks to the basic melody, following a well-worn path, only occasionally employing her soon-to-be trademark wail. The longer alternate take is Aretha reinterpreting the arc of the song. She reshapes the melody, stretching out and bending notes. There are no strings to get in the way. It’s a jazz interpretation. It's great for what it is but it's still not soulfully in the Aretha mold.

During the sixties even a cursory glance will enable one to easily chart the movement of black musicians from straight up assimilation and entertainment to defiant embracing of ethnic pride and tacit purveying of coded messages of upliftment and encouragement. The Queen In Waiting (The Columbia Years (1960 – 1965) is more than a collection of early Aretha Franklin; the double-CD set is an incisive and insightful documenting of a major record company trying to push for musical stasis against an emerging voice that was willfully headed deep into the heart of then emerging blackness.

Uniformly the arrangements are either saccharine verging on schmaltzy—dripping with strings, vocal chorus, and muted horns—or else we’re subjected to tuxedoed R&B, the fire of the funk dampened down to a simmer. There is neither the full out consciousness of jazz nor the buoyant spirit of raucous R&B, not to mention precious little of the emotional catharsis of gospel. Fortunately, Aretha’s magnificent voice could not be kept in the kitchen preparing meatloaf, mash potatoes, succotash with apple strudel for dessert.

Notably there are no originals by Aretha in this collection. She's interpreting other people's music. She ranges from a direct hommage to Ray Charles during which she literally calls his name ("Hard Times") and a hommage to Dinah Washington ("Nobody Knows The Way I feel This Morning") to covers of standards ("Skylark") and even a cover of Dionne Warwick ("Walk On by"). Columbia tried a little bit of everything but was never able to come up with a market success.

If you listen to the two versions of “Skylark” you can clearly hear what’s up. On the short version, which was initially released, Aretha has to fight her way through the strings. She sticks to the basic melody, following a well-worn path, only occasionally employing her soon-to-be trademark wail. The longer alternate take is Aretha reinterpreting the arc of the song. She reshapes the melody, stretching out and bending notes. There are no strings to get in the way. It’s a jazz interpretation. It's great for what it is but it's still not soulfully in the Aretha mold.

As a pianist, Aretha had the chops to do jazz but based on the body of her recorded work, I think she was obviously much more interested in what is today recognized as soul music, i.e. the mix of jazz, gospel and R&B. Witness what Aretha does on the end of the alternative version of “Skylark”: the way she holds notes, the way she bobs and weaves like Sugar Ray Robinson. Although there is no knockout, it’s a unanimous decision won on points.

The studio musicians do what they were hired to do and not surprisingly most of the time there is no strong interaction. Once again, professionalism is a limitation. The musicians needed to be un-reined, encouraged to go for it instead of just playing the changes. But on the other hand, had that happened, they probably would have been fired. Tracks like “Skylark (Alternate Version)” were initially canned, only coming to light decades later as Columbia repackages and rebottles early Aretha. We must admit though, early Aretha is more attractive than early, middle or late music from most of her peers.

Beyond the great and distinctive voice, Aretha had a knack for investing her life into the music. Even in these corseted arrangements, Aretha found little vocal nuances and impromptu verbal asides that personalized the music. On ”Drinking Again,” (another Dinah Washington associated song) Aretha calls out the name of a particular liquor. Indeed, on all of these cuts we hear the beginnings of all the trademark techniques that twenty and thirty years later became stultifying vocal clichés and mannerisms over-used by lesser singers, some of whom may have thought they were paying homage to greatness when all we were actually getting was a pale and too often annoying misrepresentation of what Aretha did with grace and masterful expertise.

As a pianist, Aretha had the chops to do jazz but based on the body of her recorded work, I think she was obviously much more interested in what is today recognized as soul music, i.e. the mix of jazz, gospel and R&B. Witness what Aretha does on the end of the alternative version of “Skylark”: the way she holds notes, the way she bobs and weaves like Sugar Ray Robinson. Although there is no knockout, it’s a unanimous decision won on points.

The studio musicians do what they were hired to do and not surprisingly most of the time there is no strong interaction. Once again, professionalism is a limitation. The musicians needed to be un-reined, encouraged to go for it instead of just playing the changes. But on the other hand, had that happened, they probably would have been fired. Tracks like “Skylark (Alternate Version)” were initially canned, only coming to light decades later as Columbia repackages and rebottles early Aretha. We must admit though, early Aretha is more attractive than early, middle or late music from most of her peers.

Beyond the great and distinctive voice, Aretha had a knack for investing her life into the music. Even in these corseted arrangements, Aretha found little vocal nuances and impromptu verbal asides that personalized the music. On ”Drinking Again,” (another Dinah Washington associated song) Aretha calls out the name of a particular liquor. Indeed, on all of these cuts we hear the beginnings of all the trademark techniques that twenty and thirty years later became stultifying vocal clichés and mannerisms over-used by lesser singers, some of whom may have thought they were paying homage to greatness when all we were actually getting was a pale and too often annoying misrepresentation of what Aretha did with grace and masterful expertise.

Finally, it is clear: second tier Aretha Franklin is way above the top draw of lesser lights. Indeed, being less than Aretha is actually not a mark of inferiority, after all what light is brighter than the sun?

Actually, there are a number of other leading lights, just not within the galaxy of soul music. In jazz and gospel, and to a lesser extend blues, there are major luminaries but when it comes to soul music, even thirty-some years after her ascendancy, Aretha’s influence and impact on soul music is still so omnipotent that we measure the brightness of everyone else by how closely they approach the mega-watt illumination of our lady of soul, Aretha Franklin.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Some of this music is really good

It's been said that Aretha Franklin could've sang the phone book and made it sound good. With records like "Mockingbird," I guess her producers were trying to prove that theory true. Like most statements of its kind, it is of course untrue. "Mockingbird" is pretty dull. Some of this music is really good though. The strings on "Try A Little Tenderness" are kind of distracting, but Aretha's voice is soooo beautiful on this song. It's a tune where her youthfulness and relative inexperience is actually a plus. I can't help comparing Aretha's version to Otis Redding's and it's in making that comparison that the clear, ringing quality of Aretha's vocals really stands out.

Aretha's versions of songs like "Lee Cross," "God Bless The Child" and "Walk On By" aren't necessarily great, but they are a lot of fun. I also really like the alternate version of "Skylark." I never really got the Dinah Washington comparison, but listening to this tune and thinking about Dinah ballads like "I Don't Hurt Anymore," I can finally understand what people are talking about. You can tell Aretha's producers were probably reigning her in on these recordings, but on some of them (like the alternate version of "Skylark") I think it's the right approach. I dig it.

In general, I really enjoy hearing these older performances. It's great to hear Aretha sing back when her voice was strong and clean and the instrumentation actually fit her style. I hate hearing her try to work over all of these drum machines and electronic keyboards. It just doesn't sound right.

On a different subject, Baba, you make a good point when you talk about the arc of Aretha's career. We talk a lot about the greatness of seventies soul. (And by 'we,' I don't just mean we here at BoL; I mean just about everybody who talks about black music at all.) The thing we have to remember is the greatness of the music of that era was, in part, the culmination of several social upheavals. Change was the norm. The aphorism relevant to this situation is: a rising tide lifts all boats. It's not just Aretha whose music followed this arc. Think of artists like James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, the Isley Brothers, the O'Jays, etc. They all followed that arc of pop to soul to and back to pop (the latter step excluding Bob, who died early enough to be spared the inglorious fall from grace). They all started out singing mostly love songs in the sixties then followed the social trend to add in social commentary and protest music in the seventies. I don't think it was a matter of better or different artists; I think it was a matter of different times. What I'm trying to say is, if Aretha had been born in 1973, she wouldn't be Aretha, she'd be Mary J. Blige. That's my theory anyway. Thanks for the science, Baba. Later!

—Mtume ya Salaam

Finally, it is clear: second tier Aretha Franklin is way above the top draw of lesser lights. Indeed, being less than Aretha is actually not a mark of inferiority, after all what light is brighter than the sun?

Actually, there are a number of other leading lights, just not within the galaxy of soul music. In jazz and gospel, and to a lesser extend blues, there are major luminaries but when it comes to soul music, even thirty-some years after her ascendancy, Aretha’s influence and impact on soul music is still so omnipotent that we measure the brightness of everyone else by how closely they approach the mega-watt illumination of our lady of soul, Aretha Franklin.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Some of this music is really good

It's been said that Aretha Franklin could've sang the phone book and made it sound good. With records like "Mockingbird," I guess her producers were trying to prove that theory true. Like most statements of its kind, it is of course untrue. "Mockingbird" is pretty dull. Some of this music is really good though. The strings on "Try A Little Tenderness" are kind of distracting, but Aretha's voice is soooo beautiful on this song. It's a tune where her youthfulness and relative inexperience is actually a plus. I can't help comparing Aretha's version to Otis Redding's and it's in making that comparison that the clear, ringing quality of Aretha's vocals really stands out.

Aretha's versions of songs like "Lee Cross," "God Bless The Child" and "Walk On By" aren't necessarily great, but they are a lot of fun. I also really like the alternate version of "Skylark." I never really got the Dinah Washington comparison, but listening to this tune and thinking about Dinah ballads like "I Don't Hurt Anymore," I can finally understand what people are talking about. You can tell Aretha's producers were probably reigning her in on these recordings, but on some of them (like the alternate version of "Skylark") I think it's the right approach. I dig it.

In general, I really enjoy hearing these older performances. It's great to hear Aretha sing back when her voice was strong and clean and the instrumentation actually fit her style. I hate hearing her try to work over all of these drum machines and electronic keyboards. It just doesn't sound right.

On a different subject, Baba, you make a good point when you talk about the arc of Aretha's career. We talk a lot about the greatness of seventies soul. (And by 'we,' I don't just mean we here at BoL; I mean just about everybody who talks about black music at all.) The thing we have to remember is the greatness of the music of that era was, in part, the culmination of several social upheavals. Change was the norm. The aphorism relevant to this situation is: a rising tide lifts all boats. It's not just Aretha whose music followed this arc. Think of artists like James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, the Isley Brothers, the O'Jays, etc. They all followed that arc of pop to soul to and back to pop (the latter step excluding Bob, who died early enough to be spared the inglorious fall from grace). They all started out singing mostly love songs in the sixties then followed the social trend to add in social commentary and protest music in the seventies. I don't think it was a matter of better or different artists; I think it was a matter of different times. What I'm trying to say is, if Aretha had been born in 1973, she wouldn't be Aretha, she'd be Mary J. Blige. That's my theory anyway. Thanks for the science, Baba. Later!

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Monday, December 24th, 2007 at 1:06 am and is filed under Cover. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

| top |