JOHN COLTRANE / “The Drum Thing”

It was 1967. I was a sergeant in the military, on a nuclear missle training base, Fort Bliss, Texas. Because I had already done a year in Korea and was a grade E-5, I was a supervisor of trainees which reductively meant I had a bunch of time on my hands. So I decided to follow a dream and become a drummer.

It was like I had two jobs: from 7am to 3pm I worked (well, not really worked, supervised and taught, although most of the teaching turned out to be how to use a paint brush to paint rocket launchers; seems like we had about ten of them sitting in the desert and by the time we got to number ten, the blowing sand would have worn-off most of the paint on launcher number one so we would start all over again), and from about 4:30pm to 8:30 or 9pm, I would practice and play music. Since I didn’t have to stand in formation and didn’t have to wait in the chow line (as a sergeant I could just walk right in to the front of the line whenever I arrived), I was therefore able to get to the USO before most of the other soldiers, which meant that I could check out the one full set of drums first and have roughly an hour to practice by myself before we started jamming.

There are three essentials to getting good as a drummer. One is practice. Two is study (i.e. listening to good drummers). Three, and the most important, was actually playing. Jamming with the fellers was good but it was not the same as actually performing on a gig. In fact, I considered our nightly jam sessions group practice. Ultimately, nothing replaces what you learn by actually playing for an audience.

So who was I listening to? A lot of people. But there was a threesome who were my main inspirations: Art Blakey, Max Roach and Elvin Jones. Later, I would add Tony Williams to that group.

Art Blakey’s work on the Dizzy Gillespie composition “A Night In Tunisia” (specifically the one on the Blue Note album of the same name) was numero uno in teaching me. Blakey was so powerful. He felt like an extra heart beating inside you. Made you coordinate you breathing with his rhythms, your head moved with his sock cymbal, and you just had to bob and weave like Muhammad Ali when Blakey started those press rolls and cymbal crashes. And when he used his elbow to alter the drum’s pitch, ah, man there wasn’t even a sliver of space between him and perfection. (I knew that no human was perfect but damn, you could run a German train on Blakey’s ability to keep time.)

First I memorized the solo; in fact, I memorized the whole song from the opening bombs to the concluding tom tom thump. Then I spent weeks trying to do with Art did. Of course, I never was able to duplicate what Mr. Blakey did with such seeming ease but when I played “Night In Tunisia” everybody could hear what I was doing. I even won a talent show contest on the base playing Blakey’s solo.

That was a hell of band Blakey had. Especially that demon Lee Morgan filling up my ears with lava-hot trumpet solos. Where Dizzy (who was Lee’s idol) played with a bright, light and agile tone, Lee Morgan had this swagger as if he had shitkickers on and intentionally walked down the street with one foot in the gutter. I loved it and, of course, I admired the way Art Blakey was the high sheriff of hard bop, pile driving the rhythms atop which Lee erected jazzily designed, aural skyscrapers.

Maybe it was because I had seen Blakey live two years earlier, had seen him dramatically end a breath-taking solo by throwing his drum sticks in the air. I was, as we say in New Orleans, too through!

But then I copped this Max Roach record: Speak, Brother, Speak. Max made me dance. At that time I hadn’t yet heard him live, my hero worshiping days had not yet arrived, but nevertheless, I was mighty, mighty impressed with the melody in his drums. Art Blakey had driving rhythms, Max has beguiling melody. The only cat I knew of close to what Max had was Mingus’ main drummer, Danny Richmond, and can’t forget Monk’s drummer Frankie Dunlop. But both of those cats mostly played the music of their respective leaders, Max was playing everything.

I never learned any Max Roach solos. I took structure from him. A few special techniques. An appreciation for reaching for the widest variety of tones from the drums.

Three was Elvin Jones; the systole to John Coltrane’s musical diastole. I spent a lot of time with my mouth open, holding my breath when listening to Elvin. Nobody did what he did. Shit, not even no two-bodies was able to do what he did. Everybody else played rhythm, he played wind, thunder, earthquake and volcano; river current and ocean undertow, Elvin Jones was a force of nature. Either you were him or you weren’t, trying to play like him was impossible.

There was no sense in practicing “at” that. Just like you didn’t practice catching the spirit in church, either you caught it or you didn’t (or, more accurately either it caught you, or it didn’t). Of course, I wasn’t the only drummer in the world who wasn’t Elvin Jones. I had plenty of company.

I don’t know if you have ever stood outside during a thunderstorm, not necessarily in the rain, maybe under an overhang, or in a garage with the door up, or even on a covered porch, but the air is literally electric then, and the crack of the lightening, the rumble of the thunder, the way the wind whips the rain, the cross-rhythms of precipitation tap dancing on the side of a house or the roof of a car, I don’t know if you have ever done that but if you have, then you have felt some of what it felt like listening to Elvin Jones.

Jones’ playing was so complex. There were no regular rhythm patterns to memorize. No one-two-three-four beat you could count. No simple reoccurring downbeat to reference. Elvin Jones just flat out played: beneath his hands the drums were no longer simply a percussion instrument, the skins, wood, sticks and metal became the four earthly elements. And that solo on “The Drum Thing” (from Coltrane's album Crescent) was so astounding because it was soft thunder. There was nothing noisy about it but it was so moving.

If you were a drummer and listened to Elvin Jones you could never become vain because you knew no matter how good you got, there was somebody hotter than the sun, somebody whose sense of rhythm was as strong as gravity working on the planets circling the sun at different speeds, slanted at different angles and making inexact but perfectly coordinated rotations. Imagine Coltrane is the sun and Jones is all nine planets spinning and rotating simultaneously.

Blakey's "A Night In Tunisia," Roach's "Speak, Brother, Speak," and Elvin Jones on Coltrane's composition "The Drum Thing," are three classic drummers recording three instructional classics of jazz drumming. Although they are neither the first word in jazz drumming, and certainly not the last word in jazz drumming, they are the pinnacles of their respect styles and time periods. For me, they were both beacons and milestones, guiding me forward as I pursued a career as a drummer and standing as standards to mark off my progress.

In June of 1968 when I was discharged I went home for a few days to see my family. I left my drums in El Paso. While in New Orleans I went looking to see what the drummers were doing at home. I ran across Smokey Johnson and James Black, David Lee and Zigaboo.

I had become good. Was in two bands and a highly sought sub. But man, my homies hurt me. I looked deep into the mirror one day soon after arriving and counted the carets. I had thought of myself as a diamond who needed some polishing and refining. I knew I wasn’t no where near Elvin Jones, or Blakey or Roach for that matter, but I “knew” I was good, or so I thought. The truth was I was only good and what I really wanted was to be great.

At that point in my life, I took the left fork and pursued writing. I consciously gave up on being a drummer. I never saw my beloved drums again.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Talking about drummers

It's very, very interesting to read a writer who used to be a drummer talking about drummers. I listened to all of three of these tracks twice each while cleaning the house yesterday. Although my favorite was easily "Speak Brother Speak," I enjoyed all three.

But then I'm sitting here reading Kalamu's comments and I feel compelled to listen to the tracks again. Especially the Coltrane tune. Of course, I have the Crescent CD and I've heard "Drum Thing" many times. I've never really focused in on what Elvin is doing on the drums though. (Funny, right? Especially given that the song is named "The Drum Thing.") Usually, I hear Elvin's solo as a bridge between Trane's two brief statements. Coltrane is such a commanding, brilliant presence - it's hard not to focus on him. Anyhow, I may not have grown up idolizing jazz musicians like Trane and Elvin, but I did grow up standing under overhangs, watching the lightning and listening to the thunder while I waited for one of our many storms to pass. That's a very good description of what Elvin's drums sound like. He has the charged-up, crackling intensity of atmospheric electricity; the gut-pounding power of thunder; and he has the ability to completely engulf you in his playing, like the tender yet unrelenting rain. Wow.

I can hear what Kalamu describes in the Blakey tune too. It's not my favorite—for some reason, "A Night In Tunisia" has always made me think of cruise ships and cocktails—but I hear both the power and the precision.

And then there's "Speak, Brother, Speak." Talk about a jazz tune. Man! Not long ago we did an entire week where we focused on the classic Miles Davis album Kind Of Blue. I remember writing then that Kind Of Blue was the jazz album. Well, "Speak, Brother, Speak" may not have the noteriety of Kind Of Blue, but I sat there listening to it, thinking, "This is an entire jazz album in one song!" Then the twenty-five minutes was over, I hit back-skip and listened to the whole thing again. Damn.

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, November 4th, 2007 at 12:22 pm and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

3 Responses to “JOHN COLTRANE / “The Drum Thing””

December 15th, 2013 at 5:48 am

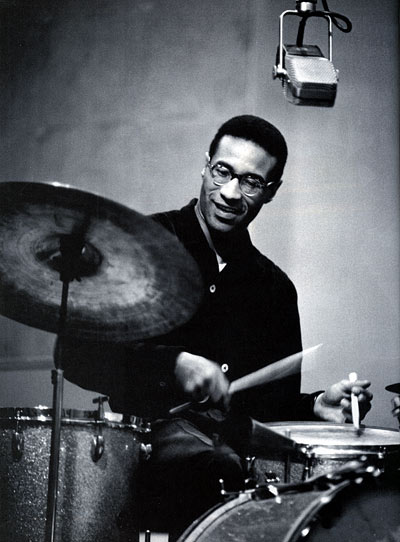

May I use the picture above (here’s your url http://www.kalamu.com/bol/wp-content/content/images/art%20blakey%2001.jpg) for a story we are doing in our church newsletter? I did not know if it was copyrighted or not and I don’t want to use the picture without permission of the owner.

Leave a Reply

| top |