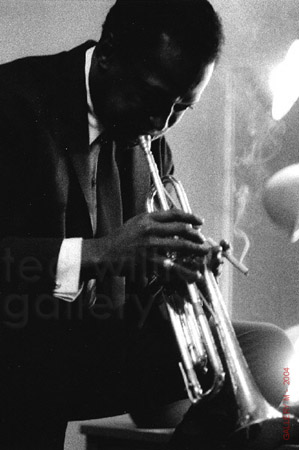

MILES DAVIS / “So What”

WHAT IS JAZZ? Kind Of Blue is the jazz record. If I was asked ‘What is reggae?’ and I could answer only in records, I’d hand over a copy of Bob Marley & The Wailers’ Natty Dread. If I was asked, ‘What is soul?’ it’d be Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. What is hip-hop? Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back. And, what is jazz? No hesitation, no need to think. Kind Of Blue. Easy.

This is the one jazz record owned by people who don't listen to jazz, and with good reason. … It was the key recording of what became modal jazz, a music free of the fixed harmonies and forms of pop songs. In Davis's men's hands it was a weightless music, but one that refused to fade into the background. In retrospect every note seems perfect, and each piece moves inexorably towards its destiny. —John Szwed, author of So What: The Life of Miles Davis

THE PLAYERS

Miles Davis – Trumpet

John Coltrane – Tenor Saxophone

Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley – Alto Saxophone

Bill Evans – Piano

Paul Chambers – Bass

James Cobb – Drums

Wynton Kelly – Piano on “Freddie Freeloader”

THE PLAYERS

Miles Davis – Trumpet

John Coltrane – Tenor Saxophone

Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley – Alto Saxophone

Bill Evans – Piano

Paul Chambers – Bass

James Cobb – Drums

Wynton Kelly – Piano on “Freddie Freeloader”

Still acknowledged as the height of hip four decades after it was recorded, Kind of Blue is the premier album of its era, jazz or otherwise. Its vapory piano-and-bass-phrased introduction is universally recognized. Classical buffs and rage rockers alike praise its subtlety, simplicity and emotional depth. Copies of the album are passed to friends and given to lovers. The album has sold millions of copies around the world, making it the best-selling recording in Miles Davis's catalog and the best-selling classic jazz album ever. Significantly, a large number of those copies were purchased in the past five years, and undoubtedly not just by old-timers replacing worn vinyl: Kind of Blue is even casting its spell on a younger audience more accustomed to the loud-and-fast esthetic of rock and rap. —Ashley Kahn, author of Kind of Blue: The Makings of the Miles Davis Masterpiece

I think it [Kind Of Blue] is a universal epitome of sophistication in music development. It's a forum for a great artist to perform at the peak of their development - it's just something that will endure for hundreds of years, maybe a thousand years. —Elvin Jones, legendary jazz drummer

Kind of Blue is a jazz album that has transcended the genre of jazz and become one of a handful of recordings whose very existence changes everything. … Listening to this album will immerse you at once in a world that is dark, brooding, sophisticated, very cool, sexy, and langorous. Bottom line is: if you don't have this record in your collection, you don't have a collection. —Jazzitude.com

Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings and I think without exception the first complete performance of each was a "take." —Bill Evans, from the original liner notes of the Kind Of Blue LP

In the church of jazz, Kind of Blue is one of the holy relics. Critics revere it as a stylistic milestone, one of a very few in the long tradition of jazz performance, on equal footing with seminal recordings by Louis Armstrong's Hot Fives and Charlie Parker's bebop quintets. Musicians acknowledge its influence and have recorded hundreds of versions of the music on the album. Record producer, composer, and Davis confidant Quincy Jones hails it as the one album (if that were the limit) that would explain jazz. —Ashley Kahn, author of Kind of Blue: The Makings of the Miles Davis Masterpiece

1959

That’s right: Trane had already taken Giant Steps before Miles created Kind of Blue. Trane had already won the heavyweight championship and was now about to play PGA championship golf.

Giant Steps was the last major development for jazz combos playing on chord changes in modern jazz. Nobody surpassed that statement for playing the changes. Period.

Giant Steps was recorded April 1, 1959. Kind of Blue was recorded April 6, 1959. April fool, Trane had been there and done that before Miles.

Think about the humongous achievement for this individual to go from the epitome of chordal investigation to no chords at all and to blow the hell out of both sessions. Trane!

To (appropriately) use the vernacular: Trane is a motherfucker!

Mtume, as you correctly noted every one of Trane’s solos on Kind of Blue is a lyrical masterpiece of such stellar quality that when he enters the room you stand up and salute by singing along with the opening notes. Immediately. How does a muscian shift gears like that going from the chordal complexity of Giant Steps to the lyrical simplicity of Kind of Blue?

You just got finished taking Giant Steps and now you’re going to slow down and do a beautiful, graceful slow dance. Oh wow.

You’re right, Mtume, solo for solo, Trane is the clear leader on Kind of Blue even though it’s Miles’ masterpiece because Miles conceived it and brought together the ingredients, the musicians to make it happen.

So Miles does deserve his accolades but think on this: what if Trane had not made the session. What would Kind of Blue have been without Trane?

Trane would still have had Giant Steps and Miles, well, look at the albums that came after Trane left Miles. Some great, great music but not until over five years later in 1964 when Wayne was brought into the fold, not until then was Miles able to begin making music that changed the direction of jazz.

After Trane left, Miles went back to standards for the most part (and he did it brilliantly no doubt, but it was still standards and not new directions) but Coltrane was slaying dragons right and left, opening new vistas.

One more thing to think about: the myth that Kind of Blue was conceived and completed in one recording session in the studio, the myth that the music had not existed like that before, the myth that on that magical day in April the stuff just Topsy-like jumped out full blown.

Not so. And guess what? There’s recorded evidence that Miles had not only been thinking through this music, the fact is Miles had already composed and recorded the opening statement, “So What.” Indeed, it was more than just a recording session, there was a tv broadcast.

On April 2, 1959 on “The Robert Herridge Theater Show,” Miles performed “So What” with the Gil Evans Orchestra. In the orchestra was John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb. Most deep jazzheads have seen the program but most of us have never connected the dots.

Miles and the band, minus Cannonball, recorded “So What” four days before the Kind of Blue session. And not only that, “So What” was recorded within the context of the Gil Evans orchestra. The song had been arranged. Miles had heard all kinds of possibilities plus Trane had played the song before.

You see, Kind of Blue is indeed a major, if not (arguably) “the” major jazz recording of all time, but King of Blue was not an instant masterpiece that just happened without any forethought on the part of Miles and other band members.

I know this is a lot to think about, so take your time. Whether you get on the Trane or continue traveling with Miles is not even the question. I’m just saying recognize that we are talking about a period in the history of the music when history was being made right and left, a period when all the great creators was great creating!

(Oh, yeah, guess when Dave Brubeck recorded the Time Out album with the hit song "Take Five" on it? (No, don’t do it, Kalamu, don’t hurt ‘em.) It was 1959.

I say it again: 1959. It was a hell of a year for music.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

That’s right: Trane had already taken Giant Steps before Miles created Kind of Blue. Trane had already won the heavyweight championship and was now about to play PGA championship golf.

Giant Steps was the last major development for jazz combos playing on chord changes in modern jazz. Nobody surpassed that statement for playing the changes. Period.

Giant Steps was recorded April 1, 1959. Kind of Blue was recorded April 6, 1959. April fool, Trane had been there and done that before Miles.

Think about the humongous achievement for this individual to go from the epitome of chordal investigation to no chords at all and to blow the hell out of both sessions. Trane!

To (appropriately) use the vernacular: Trane is a motherfucker!

Mtume, as you correctly noted every one of Trane’s solos on Kind of Blue is a lyrical masterpiece of such stellar quality that when he enters the room you stand up and salute by singing along with the opening notes. Immediately. How does a muscian shift gears like that going from the chordal complexity of Giant Steps to the lyrical simplicity of Kind of Blue?

You just got finished taking Giant Steps and now you’re going to slow down and do a beautiful, graceful slow dance. Oh wow.

You’re right, Mtume, solo for solo, Trane is the clear leader on Kind of Blue even though it’s Miles’ masterpiece because Miles conceived it and brought together the ingredients, the musicians to make it happen.

So Miles does deserve his accolades but think on this: what if Trane had not made the session. What would Kind of Blue have been without Trane?

Trane would still have had Giant Steps and Miles, well, look at the albums that came after Trane left Miles. Some great, great music but not until over five years later in 1964 when Wayne was brought into the fold, not until then was Miles able to begin making music that changed the direction of jazz.

After Trane left, Miles went back to standards for the most part (and he did it brilliantly no doubt, but it was still standards and not new directions) but Coltrane was slaying dragons right and left, opening new vistas.

One more thing to think about: the myth that Kind of Blue was conceived and completed in one recording session in the studio, the myth that the music had not existed like that before, the myth that on that magical day in April the stuff just Topsy-like jumped out full blown.

Not so. And guess what? There’s recorded evidence that Miles had not only been thinking through this music, the fact is Miles had already composed and recorded the opening statement, “So What.” Indeed, it was more than just a recording session, there was a tv broadcast.

On April 2, 1959 on “The Robert Herridge Theater Show,” Miles performed “So What” with the Gil Evans Orchestra. In the orchestra was John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb. Most deep jazzheads have seen the program but most of us have never connected the dots.

Miles and the band, minus Cannonball, recorded “So What” four days before the Kind of Blue session. And not only that, “So What” was recorded within the context of the Gil Evans orchestra. The song had been arranged. Miles had heard all kinds of possibilities plus Trane had played the song before.

You see, Kind of Blue is indeed a major, if not (arguably) “the” major jazz recording of all time, but King of Blue was not an instant masterpiece that just happened without any forethought on the part of Miles and other band members.

I know this is a lot to think about, so take your time. Whether you get on the Trane or continue traveling with Miles is not even the question. I’m just saying recognize that we are talking about a period in the history of the music when history was being made right and left, a period when all the great creators was great creating!

(Oh, yeah, guess when Dave Brubeck recorded the Time Out album with the hit song "Take Five" on it? (No, don’t do it, Kalamu, don’t hurt ‘em.) It was 1959.

I say it again: 1959. It was a hell of a year for music.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Food for thought Hmmm. Definitely food for thought. I knew about The Shape Of Jazz To Come and I've read about Miles' irritation that he was, in a way, upstaged by Ornette's album (as much by the title as by the music). Miles always had one eye on history. He knew he was doing something revolutionary, something new. He wanted to be alone on that mountain. Obviously, he wasn't. What I didn't know was how many revolutionary (musically) jazz albums dropped during that same year. And no, I didn't know that Trane recorded Giant Steps a mere week before he played on the Kind Of Blue sessions. That's almost too much to believe, honestly. The man is peerless. And on the whole Miles v. Trane thing, I don't think it's about arguing over who is "better." By almost any standard of musicianship, Trane was the more complete musician. It doesn't take a jazzhead to recognize that. To me, it simply comes down to a matter of taste. And it certainly isn't a mutually exclusive choice. Meaning, I like my Miles records and I like my Trane records. But if I can only keep the music of one jazz artist, I'm going to choose Miles. Hey, look at it this way: if I keep my Miles records, I get Trane and Miles. Unless Kalamu is about to spring another surprise on me, it doesn't work the other way around. Hey, Baba. Thanks as always for the insight. I'm out! —Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, September 30th, 2007 at 1:46 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

2 Responses to “MILES DAVIS / “So What””

September 30th, 2007 at 8:52 pm

thanks for the great writing and insight. just a thought to continue the discussion about miles and trane – who was the ‘better’ bandleader?

kalamu sez

no contest. miles was the better band leader. now if you want to really start an argument ask the question who had the better band? as is to be expected, i’d vote for the classic coltrane quartet but of course there is a major argument to be made for the shorter/hancock/carter/williams quintet that miles led (or for that matter for miles’ trane/garland/chambers/jones quintet). i think trane’s classic quartet has the edge in influential album production. but you know this is the stuff of endless discussion/debate among jazzheads, fortunately for all of us, regardless of our opinion, we have both miles and trane to discuss. can we imagine jazz without miles and without trane?

October 1st, 2007 at 3:06 am

Who had the better band? very tough decision and you’re right, it is great not to have to make it. dropped an extract below from Hancock on Davis. He talks about ‘So what’ and gives some insight into Davis’ awesome ability to pull something together… Do you have a specific favorite memory of playing with him? One of the most important ones to me — we were playing, I believe, in Stuttgart, Germany. This might’ve been in 1965. It was one of those nights when the band was particularly on. I mean, it started with the first note. We were burning. And during the middle of "So What," Wayne Shorter played this great solo, Miles built his solo up to this peak, Tony Williams was firing away on drums, and we had the audience in the palm of our hands. Miles blows up to this peak, and all of a sudden I played this chord that was so . . . wrong [laughs] — it just came out of nowhere. I thought I’d destroyed the evening. It was horrible, and I was stuck with it, because I played it. Miles took a breath, and played some notes that made my chord right. It was like alchemy — "How did he do that?" Did you talk about it later? I probably did, but he probably gave me some strange answer [laughs]. But after many, many years, I figured out the answer myself. One of the great things about Miles was that when he played, he was not judgmental. If it happens, it was supposed to happen. He tried to figure out a way to make it work. I try to apply that to my music. And when I began practicing Buddhism, it clarified that this concept is not one that’s just relegated to music. This is a great lesson for life — to take circumstances, whatever they are, without judgment, and try to figure out how to make them work.

kalamu sez

speaking of "wrong notes" and making things right, and speaking of budhism, one of my favorite jazz stories is about monk who is reported to have said: there are no wrong notes, it all depends on what you put before it or put after it!

i believe the masters are the masters not because they are perfect or because they are always correct but rather because they accept all and work with the reality of what is, or as another master said, this time stevie wonder (and it helps to hear his cadence and how he emphasizes the different words): you GOT to WORK with WHAT you GOT!

Leave a Reply

| top |