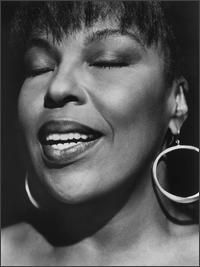

ROBERTA FLACK / “Sweet Georgia Brown”

A week or so ago, I said the music did not change much from what Louis Armstrong laid out until Coltrane took it in a completely different direction. I’d like to give a “partial” illustration of what I meant. Here are four different versions of the same basic song. In this case, “basic” refers to the harmonic underpinning, or what is commonly called “the chord changes.”

Using chord changes as the basis for a new song is the main way music worked in 20th-century America. Here is “Sweet Georgia Brown,” a popular song that has been recorded numerous times by numerous musicians representing different eras and different approaches. These four versions are actually more than simply covers even though the common element in all four is use of the basic harmony, i.e. the changes.

The first version is by “Brother Bones” and is probably the most popular of all of them thanks to the Harlem Globetrotters exhibition basketball team which toured worldwide. According to the Whistling Records website:

Brother Bones recorded one of the most instantly recognizable songs of the 20th century, yet remains a virtual unknown, overshadowed by his own hit record and the world famous basketball team that adopted it as their official theme. Born Freeman Davis in Montgomery, Alabama, Brother Bones was a one-time shoe shine boy, working at stands in the vestibules of local barber shops. While shining, he would whistle, snap his shoeshine rag and pop his brushes in rhythm to records being played on an old Victrola. Brother Bones became known around town as "Whistling Sam." He would also tap dance and play the bones and knives, perfecting a style which used four bones in each hand whereas most bones players used only two. According to Tempo Records, Brother Bones was discovered by their president while playing in a Chinese restaurant in downtown Los Angeles and shortly after, "Sweet Georgia Brown" was playing on the radio across the nation.

Sweet Georgia Brown has been recorded by everyone from Bing Crosby to Louis Armstrong - even The Beatles! But by far, the most famous variation was the whistling, bone-clacking version recorded by Brother Bones and his Shadows in the late 1940's. Adopted in 1952 as the theme song of the Harlem Globetrotters, the catchy tune has been played during their pre-game warm-ups and throughout their games for decades. Millions around the world have heard it and it is probably in the top ten most listened to recordings in history. So important to the Harlem Globetrotters is "Sweet Georgia Brown" that it has become their aural trademark, much like MGM has its familiar lion's roar.

Brother Bones went on to record over a dozen songs, appear in at least three movies, perform at Carnegie Hall and was on The Ed Sullivan Show. He died in 1974 at the age of 71 and was survived by his wife, Daisy, a daughter and two grandsons.

By the way, “bones” are bones. The faq section of the website notes: “The bones are one of several types of clappers and are classified as percussive instruments. Bones in some form date back almost as far as man himself and were probably among the earliest musical instruments made. Bone playing by slaves on American plantations gave rise in the 1800's to black street bands and minstrel shows where white performers in blackface danced, sang and told jokes.”

The opening section of the song is simply bones and whistling then a piano enters but only playing the main chords of the song. The middle section is fleshed out with a bass and saxophone in addition to the piano and Brother Bones, however the instruments play in what most people would think of as an old-timey Dixieland style with that 2/4 rhythm feel. Brother Bones offers an original and charmingly unorthodox take on the song.

Next Thelonious Monk, who is sometimes referred to as the “high priest” of bebop, builds on the basic piano chords and through highly inventive rhythmic rearrangement and fitting a new melody atop the harmony, comes up with what probably sounds to most people like not only a completely different song, it also probably sounds like an unrelated song, but it’s not. Bebop was not unrelated to what went before, it was just a total rearrangement from a rhythm and melody standpoint but it retained the basic harmonic underpinnings. Monk decided to call his composition “Bright Mississippi.”

OK, are you with me thus far? Here comes the Cannonball Adderley Sextet performing a Charles Lloyd composition titled “Sweet Georgia Bright.” The very title tells you that Lloyd draws on both the original pop tune and Monk’s refashioning of the standard. If Monk was on an airplane, Lloyd is taking a rocket. The speed is the first thing that stands out. And secondly, the theme statement is so short, you can hardly hear the theme of the song before they are into the solos. Yet, it’s the same basic changes and on top of that the arrangement makes use of swing elements, specifically horn riffs behind each soloist. I remember seeing this band in the early Sixties and it was a totally exhilarating experience, especially the enigmatic Charles Lloyd (or at least that’s how he then seemed to me).

Charles Lloyd is the key. Here was a Coltrane-influenced jazz musicians who was hearing new sounds and wrote compositions that reflected his iconoclastic views. At some time in the future we’ll get deeper into Charles Lloyd, but for now let’s just stay with his composition as a variation on “Sweet Georgia Brown.”

Finally, from a musical perspective here comes the most radical version. It’s Roberta Flack with a James Brown/John Coltrane vamp approach. Listen how the bass plays a basic vamp over and over. There is no harmonic development in the sense of changes. Whenever they play the bridge of the song, the “b” in the four-part aaba structure, except for a few choice notes, the bass player lays out and returns for the “a” sections playing the repetitive figure over which the rest of the song is layered. In this way the song becomes rhythm and melody determined rather than harmony-based.

In popular music, James Brown was the person who de-emphasized the harmony. In jazz, it was Coltrane who brought this playing over bass vamps to the fore. Note: I am not arguing that either Brown or Coltrane were the first to do this, nor that they were the only ones to make radical changes in the approach to music making. Others came before Brown and Coltrane, such as Miles Davis with Kind Of Blue, as well as countless blues players. However, in popular music it was James Brown and in jazz, John Coltrane, who solidified and popularized this approach.

Moreover, it’s funny to me that of the four versions, Roberta’s version probably sounds the most appealing to folk under-thirty even though harmonically it is the most different from the other three. Hip-hop has solidified the developments that emphasize rhythm and voicings while minimizing harmonic development. Hopefully, this illustrates my point. In this regard Roberta Flack’s version is not simply a cover, instead Roberta has produced a classic remake of a classic song.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Minimizing harmonic development?

While I can't claim to be under thirty anymore (and after Monday, I won't even be able to claim to be under thirty-five  ), I do agree that the Roberta Flack is the most appealing one of these songs. I like the Monk tune too. Not really feeling Cannonball's take on things. I've heard the Brother Bones one so many times that I can't even hear it as "music" anymore. It just sounds like "Globetrotters Theme" music. Like a commercial jingle or something. Which, I guess, was partially Kalamu's point.

), I do agree that the Roberta Flack is the most appealing one of these songs. I like the Monk tune too. Not really feeling Cannonball's take on things. I've heard the Brother Bones one so many times that I can't even hear it as "music" anymore. It just sounds like "Globetrotters Theme" music. Like a commercial jingle or something. Which, I guess, was partially Kalamu's point.

Now, as far as the whole "minimizing harmonic development" discussion, I'm going to have to plead ignorance. At first, I heard nothing at all to link Roberta Flack's song to the other songs. Then, finally, I heard that it's the same melody, just slowed down a lot. As for the rest of it, I don't have a clue. I'm not entirely certain what "harmonic development" is or how to tell when it's missing or changed or what have you. Um, let me phrase. I have no idea what "harmonic development" is or how to tell when it's missing or changed. So although I'm a big fan of damn near everything Miles released from Kind Of Blue through Bitches Brew, and I'm a big fan of Coltrane from the Atlantic years through the first half of the Impulse period and although I consider J.B. the unqualified and unchallenged king of super, super heavy funk, I have to admit that I have no idea what any of these cat are doing technically.

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, September 17th, 2006 at 12:00 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

2 Responses to “ROBERTA FLACK / “Sweet Georgia Brown””

April 10th, 2016 at 7:49 am

The Brother Bones version is in 2/2, not 2/4. Bob Blumenthal always makes that mistake when he comments on Miles Davis playing things like “All Of You”. The Miles performances are in 4/4, but Paul Chambers plays in 2/2 against it during the melody statements. This builds up tension before the piece breaks loose into 4 to the bar. I would like to know who the tenor saxophone player is in the Bones version. There is no influence of Coleman Hawkins or Lester Young. He sounds a bit like Fats Waller’s tenor saxophone player, Gene Sedric. There is perhaps a bit of an influence of Bud Freeman.

Leave a Reply

| top |