CANNONBALL ADDERLEY / “Autumn Leaves”

We don't look down on any music, and we don't play anything simply for effect, Everything we play we choose to play, I announce to the audience that we don't take requests; we play things that we've recorded, so nobody has to tell me to play Mercy Mercy Mercy or anything like that, because we're going to play it anyhow. And we have a ball - that's the only way music can be for real, We do what we want to do and try to keep the audience with us. Because those are the only things that are important; whether we enjoy what we're doing and whether people enjoy what we're doing. But we can't gear anything to anybody because that's rank commercialism: "Here's an audience that likes this, so we're going to play this." That way you're not being a complete person, or a complete creative musician, and you're not really saying what you want to say. —Cannonball AdderleyIt’s hard to reduce a jazz artist to four or five minutes, even as an introduction. Usually a jazz musician works as a sideman in the beginning and then does his or her own thing later on, and generally, over the course of that process, evidences two or three major stylistic developments. So what period does one cite when you’ve got six to ten minutes to make your case? It won’t work. It really won’t work. You can play a particular piece and say why that piece is important, but covering a jazz artist’s life in brief, there’s no way, especially when you are dealing with a major creator of the music.

That said, let’s look at Julian Edwin ‘Cannonball’ Adderley. The contradictions he so successfully fused. The lyrical-monster horn-master. The jovial sorcerer whose seriousness could kill a brick. A man who led the charge into jazz fusion on the blue-collar side of the aisle and yet, also produced quintessential hard bop recordings. A lot of Cannon’s canon was specifically designed to reach people who thought they didn’t dig jazz, or who wanted to dance more than sit and think, or who liked to party more than meditate, and as a result a lot of people write him off as lightweight but my man was deeper than the shallowness of the glib evaluation of pseudo-hip, solipsistic jazz critics.

‘Cannonball’ Adderley was born in Tampa, Florida on September 15, 1928. Cannon’s nickname was a corruption of his childhood moniker, ‘cannibal,’ appended to him because of his prodigious appetite. He died of a stroke in Gary, Indiana on August 8, 1975.

Cannonball seemed destined to be a jazz musician. Following his college studies and following in the footsteps of his father (a trumpet player who had also been a music educator), Jullian Adderley became a high school band director at Dillard High School in Fort Lauderdale, Florida from 1948-1950. In 1955 he moved to New York. Shortly thereafter he sat in with bassist Oscar Pettiford on a gig at the Café Bohemia, and seemingly overnight he was hailed as the second coming of Bird (Charlie Parker).

Although Cannonball had the technical facility to play Parker-like licks, he also had the sensitivity of a Benny Carter and the warm tone of a Johnny Hodges. Whether jamming with a hard-bop combo or floating melodically atop a bed of strings, Cannonball was both comfortable and accomplished.

Cannon’s first attempts at starting his own band failed and he joined Miles Davis’ group in 1957. He stayed with Miles until 1959, leaving at approximately the same time as Coltrane.

That said, let’s look at Julian Edwin ‘Cannonball’ Adderley. The contradictions he so successfully fused. The lyrical-monster horn-master. The jovial sorcerer whose seriousness could kill a brick. A man who led the charge into jazz fusion on the blue-collar side of the aisle and yet, also produced quintessential hard bop recordings. A lot of Cannon’s canon was specifically designed to reach people who thought they didn’t dig jazz, or who wanted to dance more than sit and think, or who liked to party more than meditate, and as a result a lot of people write him off as lightweight but my man was deeper than the shallowness of the glib evaluation of pseudo-hip, solipsistic jazz critics.

‘Cannonball’ Adderley was born in Tampa, Florida on September 15, 1928. Cannon’s nickname was a corruption of his childhood moniker, ‘cannibal,’ appended to him because of his prodigious appetite. He died of a stroke in Gary, Indiana on August 8, 1975.

Cannonball seemed destined to be a jazz musician. Following his college studies and following in the footsteps of his father (a trumpet player who had also been a music educator), Jullian Adderley became a high school band director at Dillard High School in Fort Lauderdale, Florida from 1948-1950. In 1955 he moved to New York. Shortly thereafter he sat in with bassist Oscar Pettiford on a gig at the Café Bohemia, and seemingly overnight he was hailed as the second coming of Bird (Charlie Parker).

Although Cannonball had the technical facility to play Parker-like licks, he also had the sensitivity of a Benny Carter and the warm tone of a Johnny Hodges. Whether jamming with a hard-bop combo or floating melodically atop a bed of strings, Cannonball was both comfortable and accomplished.

Cannon’s first attempts at starting his own band failed and he joined Miles Davis’ group in 1957. He stayed with Miles until 1959, leaving at approximately the same time as Coltrane.

While with Miles, Cannonball performed along with John Coltrane on what is perennially picked as one of the Top Ten jazz albums of all time: Kind of Blue. And though it would be safe to choose a cut from that recording as Cannon’s feature, there is a better choice—‘better’ because it represents Cannon as a leader rather than as a sideman under someone else’s leadership, even if that someone else is Miles Davis.

Cannonball Adderley’s aptly-titled 1958 recording Somethin’ Else features—(get to this) a rarity—one of, if not ‘the,’ last appearance of Miles Davis as a sideman. In addition to Cannon and Miles, the line-up on “Autumn Leaves” is Hank Jones on piano, Sam Jones on bass and Art Blakey on drums.

I’ve chosen “Autumn Leaves” as an example of the solo prowess that wowed fellow musicians upon Cannon’s arrival on the jazz scene. He is technically daunting in leaping from register to register while alternating between quicksilver runs and glistening whole tones. But as technically gifted as he was, Cannon’s awe-inspiring technique was not his most outstanding characteristic. Whether playing ballads, swinging standards, digging into hard bop or soaring above modal jazz, throughout his career, Cannon always had an affinity for and an ability to keep the blues at the core of his sound.

While with Miles, Cannonball performed along with John Coltrane on what is perennially picked as one of the Top Ten jazz albums of all time: Kind of Blue. And though it would be safe to choose a cut from that recording as Cannon’s feature, there is a better choice—‘better’ because it represents Cannon as a leader rather than as a sideman under someone else’s leadership, even if that someone else is Miles Davis.

Cannonball Adderley’s aptly-titled 1958 recording Somethin’ Else features—(get to this) a rarity—one of, if not ‘the,’ last appearance of Miles Davis as a sideman. In addition to Cannon and Miles, the line-up on “Autumn Leaves” is Hank Jones on piano, Sam Jones on bass and Art Blakey on drums.

I’ve chosen “Autumn Leaves” as an example of the solo prowess that wowed fellow musicians upon Cannon’s arrival on the jazz scene. He is technically daunting in leaping from register to register while alternating between quicksilver runs and glistening whole tones. But as technically gifted as he was, Cannon’s awe-inspiring technique was not his most outstanding characteristic. Whether playing ballads, swinging standards, digging into hard bop or soaring above modal jazz, throughout his career, Cannon always had an affinity for and an ability to keep the blues at the core of his sound.

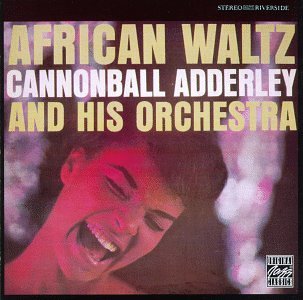

For his early years after leaving Miles, I’ve chosen a 1961 selection on which he does not solo, and which he did not write nor arrange: “African Waltz.” The woman pictured on the cover notwithstanding, this short (2-minute) big band blow-out announced Cannon’s interest in self-defined Blackness as an integral part of his music and also brought him both acclaim and popularity in the jazz community. This is a demonstration of how jazz musicians were on the cutting edge of cultural change, prefiguring the Black power and Black Arts movements which, by the mid-Sixties, would dominant African-American communities.

Cannon became a leader in the Soul Jazz arena when he had Bobby Timmons filling the piano chair and, later on, the Viennese ‘Soul Brother’ Joe Zawinul. Both men were not only excellent pianists, they were also exceptional composers. Timmons with “This Here” and Zawinul with “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” provided Cannon with two of his major hits.

For his early years after leaving Miles, I’ve chosen a 1961 selection on which he does not solo, and which he did not write nor arrange: “African Waltz.” The woman pictured on the cover notwithstanding, this short (2-minute) big band blow-out announced Cannon’s interest in self-defined Blackness as an integral part of his music and also brought him both acclaim and popularity in the jazz community. This is a demonstration of how jazz musicians were on the cutting edge of cultural change, prefiguring the Black power and Black Arts movements which, by the mid-Sixties, would dominant African-American communities.

Cannon became a leader in the Soul Jazz arena when he had Bobby Timmons filling the piano chair and, later on, the Viennese ‘Soul Brother’ Joe Zawinul. Both men were not only excellent pianists, they were also exceptional composers. Timmons with “This Here” and Zawinul with “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” provided Cannon with two of his major hits.

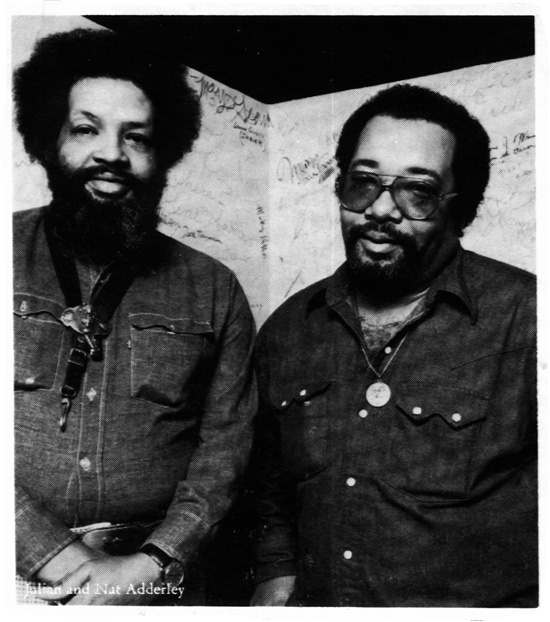

Cannon’s basic group was a quintet with his brother Nat on cornet, although from time to time they added a third horn, first Yusef Lateef and some time after, Charles Lloyd. All of his aforementioned helpmates proved to be extremely capable soloists as well as accomplished composers. Moreover, beyond his own band, Cannonball was a talent scout who boosted the careers of numerous people including Nancy Wilson, Wes Montgomery, and Chuck Mangione.

While most jazzmen are reticent, if not outright silent, preferring to let their music speak for them, Cannon was a raconteur of gargantuan ability. He could introduce a mic stand and make you applaud it’s uprightness. To say he had the gift of gab is not only a cliché, it would be a tremendous understatement. By the late Sixties, Cannonball was widely recognized as a significant spokesman for jazz. Cannon was not just quick-witted or even what some might call glib, he was informed, intelligent and genuinely warm towards everyone. In fact, that is a summation not only of his personality but also of his playing.

Cannon’s basic group was a quintet with his brother Nat on cornet, although from time to time they added a third horn, first Yusef Lateef and some time after, Charles Lloyd. All of his aforementioned helpmates proved to be extremely capable soloists as well as accomplished composers. Moreover, beyond his own band, Cannonball was a talent scout who boosted the careers of numerous people including Nancy Wilson, Wes Montgomery, and Chuck Mangione.

While most jazzmen are reticent, if not outright silent, preferring to let their music speak for them, Cannon was a raconteur of gargantuan ability. He could introduce a mic stand and make you applaud it’s uprightness. To say he had the gift of gab is not only a cliché, it would be a tremendous understatement. By the late Sixties, Cannonball was widely recognized as a significant spokesman for jazz. Cannon was not just quick-witted or even what some might call glib, he was informed, intelligent and genuinely warm towards everyone. In fact, that is a summation not only of his personality but also of his playing.

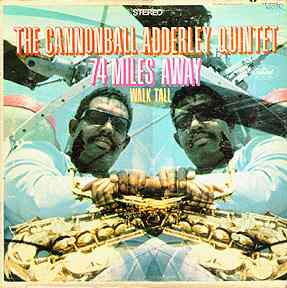

The third selection, “74 Miles Away,” is a 1967 recording from Cannonball's later period—you can hear the influence of his former cohort John Coltrane in both the style of the music as well as the style of Cannon’s solo. The line-up is Cannon and Nat on horns, Josef Zawinul on piano and electric piano, Victor Gaskin on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums. When not playing their horns, both Cannon and Nat play tambourines and at one point they place one of the tambourines inside the piano while Zawinul is soloing, thereby creating a distortion that sounds almost electronic.

The third selection, “74 Miles Away,” is a 1967 recording from Cannonball's later period—you can hear the influence of his former cohort John Coltrane in both the style of the music as well as the style of Cannon’s solo. The line-up is Cannon and Nat on horns, Josef Zawinul on piano and electric piano, Victor Gaskin on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums. When not playing their horns, both Cannon and Nat play tambourines and at one point they place one of the tambourines inside the piano while Zawinul is soloing, thereby creating a distortion that sounds almost electronic.

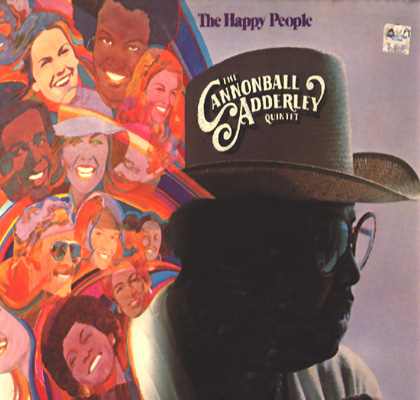

The final selection is the title piece from the The Happy People, a 1972 album that has not been released in CD format. "The Happy People" is a collaboration with Brazilian percussionist Airto and Airto’s wife, vocalist Flora Purim. The basic band is George Duke on piano and electric piano, Walter Booker on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums. They are augmented by percussionists Mayuto, Octavio and King Errison, and vocalist Olga James. Obviously Brazil was good to and for Cannonball.

While I have not included some of the more popular of Cannon’s recordings, such as “Work Song,” “Sack of Woe,” “Jive Samba,” "Mercy, Mercy" and a host of others, I hope I have successfully introduced you to (or reminded you of) the wonderful range and lyrical expressiveness of a master jazz musician: Julian Cannonball Adderley. Enjoy!

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Here is a very informative interview with Cannonball Adderley filled with historical information as well as comments that illuminate Cannonball's personality: http://www.cannonball-adderley.com/article/coda.htm

Click here to purchase Somethin' Else

It took me a while to 'hear' it

The final selection is the title piece from the The Happy People, a 1972 album that has not been released in CD format. "The Happy People" is a collaboration with Brazilian percussionist Airto and Airto’s wife, vocalist Flora Purim. The basic band is George Duke on piano and electric piano, Walter Booker on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums. They are augmented by percussionists Mayuto, Octavio and King Errison, and vocalist Olga James. Obviously Brazil was good to and for Cannonball.

While I have not included some of the more popular of Cannon’s recordings, such as “Work Song,” “Sack of Woe,” “Jive Samba,” "Mercy, Mercy" and a host of others, I hope I have successfully introduced you to (or reminded you of) the wonderful range and lyrical expressiveness of a master jazz musician: Julian Cannonball Adderley. Enjoy!

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Here is a very informative interview with Cannonball Adderley filled with historical information as well as comments that illuminate Cannonball's personality: http://www.cannonball-adderley.com/article/coda.htm

Click here to purchase Somethin' Else

It took me a while to 'hear' it

"Autumn Leaves"is one of my favorite jazz tunes. But even though Cannonball's name is above the title listed first, I'd always thought of Somethin' Else as a Miles Davis album. On "Autumn Leaves," Miles states the opening theme, takes the first solo, solos again (after Cannonball) and restates the theme. On "Love For Sale," another tune I like from Somethin' Else, Miles also plays the head and takes the first solo. Not to mention that Cannonball was still in Miles' band when they cut this album. So it's surprising to find out that Cannonball really was the leader on this album. I'd always figured they had to list Cannonball as the leader because of contractual obligations. (Miles was signed to Columbia at the time.) Then again, given that: a) I'm a Miles nut, and b) my general knowledge of jazz is virtually nonexistent, I guess I'm biased.

I'm gonna have to plead ignorance on "African Waltz." No matter how many times I listen to it, it still sounds like carnival music. Sophisticated carnival music, but still....

I've never heard "74 Miles Away" before, but I like it a lot. It took me a while to 'hear' it, but once I did, I really like the raw, blues feel of it. A lot of times, when a jazz musician or writer describes a tune as "a blues," I don't get it. All I hear is a jazz tune. Listening to a tune like "74 Miles Away," I can clearly hear the connection between jazz and blues. (And I'm glad you mentioned that bit about the tambourines; I was wondering what the buzzing sound was.)

One other note. Somethin' Else, like Kind Of Blue, is one of those rare jazz albums that is equally appealing to both casual fans and serious jazz nuts. I highly recommend it.

—Mtume ya Salaam

"Autumn Leaves"is one of my favorite jazz tunes. But even though Cannonball's name is above the title listed first, I'd always thought of Somethin' Else as a Miles Davis album. On "Autumn Leaves," Miles states the opening theme, takes the first solo, solos again (after Cannonball) and restates the theme. On "Love For Sale," another tune I like from Somethin' Else, Miles also plays the head and takes the first solo. Not to mention that Cannonball was still in Miles' band when they cut this album. So it's surprising to find out that Cannonball really was the leader on this album. I'd always figured they had to list Cannonball as the leader because of contractual obligations. (Miles was signed to Columbia at the time.) Then again, given that: a) I'm a Miles nut, and b) my general knowledge of jazz is virtually nonexistent, I guess I'm biased.

I'm gonna have to plead ignorance on "African Waltz." No matter how many times I listen to it, it still sounds like carnival music. Sophisticated carnival music, but still....

I've never heard "74 Miles Away" before, but I like it a lot. It took me a while to 'hear' it, but once I did, I really like the raw, blues feel of it. A lot of times, when a jazz musician or writer describes a tune as "a blues," I don't get it. All I hear is a jazz tune. Listening to a tune like "74 Miles Away," I can clearly hear the connection between jazz and blues. (And I'm glad you mentioned that bit about the tambourines; I was wondering what the buzzing sound was.)

One other note. Somethin' Else, like Kind Of Blue, is one of those rare jazz albums that is equally appealing to both casual fans and serious jazz nuts. I highly recommend it.

—Mtume ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, August 21st, 2005 at 12:01 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

3 Responses to “CANNONBALL ADDERLEY / “Autumn Leaves””

August 23rd, 2005 at 1:04 pm

This selection is very moving. I will admit, I find it hard to discuss jazz, it’s just something I either feel deeply or not at all. This is some straight up beautiful music.

Thanks for sharing it.

August 26th, 2005 at 3:53 pm

this is beautifully black music. kalamu’s comments, particularly about cannonball’s range, helped to put cannonball into some context. i think the first time i heard this album my mother in law, who is not what you would call a jazz enthusiast, played it for me. she really liked this album which supports the assertion that cannoball is at the intersection of the cerebral and emotional elements of jazz that appeal to both “serious” jazz listeners and others who are moved by its appeal to the internal rhythms of life. i really appreciate that, and that aspect of cannonball’s musical conception is evident on the “Happy People” cut which i really dig. i always had the romantic notion that if black musical traditions throughout the african diaspora could be fused with such success, like “Happy People” or say dizzy gillespie’s afro-cuban achievements, or some of fela’s work with roy ayers, or the great album with wayne shorter and milton nasciemento, then so could our political and social traditions be merged to create authentic cultural unity.

i loved cannonball’s playing on the album he did with nancy wilson but underappreciated him, i think, because i was always comparing his sound with that of coltrane’s on the “kind of blue” album, where they both played. trane just grabs my whole body and soul and slams it into interstellar space or some place i can feel but not fully articulate. cannonball’s lyricism is so outstanding, and his blues-playing abilities add a very unique element to his distinctive sound; its the musical equivalent, of say, the poetry of eugene redmond — very much based on the soul of black folk and equally capable of functioning at the highest intellectual levels and thereby achieving black beauty, certainly the goal in everything i want to do. thanks for the cuts and the commentary.

August 27th, 2005 at 10:19 pm

I liked very much these pieces by Cannonball and I liked very much the interplay between Miles and Cannonball.

One night I put the jukebox on continuous play and listened to it while I slept. I have become very confident with my security. I woke up to Cannonball. That was wonderful.

Thanks ever so much for what you two do.

As ever and always, Rudy

Leave a Reply

| top |