PUBLIC ENEMY feat. Branford Marsalis / “Powersaxx”

As another summer draws to a close, it seems like every audio blogger on the net is posting his or her favorite summer songs. I even saw a few blogs with discussions about what is or isn’t a true ‘summer song.’ I wasn’t planning to enter the fray, but last week, Kalamu posted some of his favorite versions of the Gershwin classic “Summertime” as well as a few versions of another ‘summer’ classic, “The Girl From Ipanema.” I enjoyed his two posts so much, I decided to do a couple ‘summer song’ posts of my own.

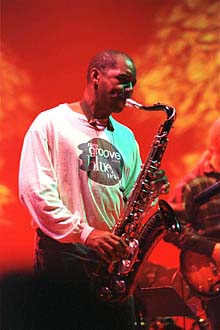

Back in 1989, Public Enemy and Branford Marsalis met on the set of Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing. Branford was working with Spike’s Dad, Bill Lee, to create the movie’s jazz-oriented score. Public Enemy had been tapped to compose and record the movie’s theme song. It was an unlikely combination, but the classically-trained jazz saxophonist Branford eventually collaborated with Public Enemy’s self-trained production team of Hank and Keith Shocklee, Eric Sadler and Chuck D AKA ‘The Bomb Squad.’ The result was “Fight The Power”—a now-classic anthem for the long, hot summer of 1998. One thing always confused me though: although the liner notes read “sax on ‘Fight The Power’ by the one and only Branford Marsalis,” there’s no sax on the record!*

A few years later, I picked up a CD single for “Brothers Gonna Work It Out”—a track from Public Enemy’s 1990 album Fear Of A Black Planet. The fourth track, something called “Powersaxx,” showed me, emphatically, what had happened to all of Branford’s work. Damn!

“Powersaxx” is the instrumental version of “Fight The Power” with simultaneous, chopped-up sax solos from Branford layered atop the mix—one solo in the left channel, one in the right. (A tribute to Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz or complete coincidence? Dunno.) I found out later that there were probably some creative differences in the studio between the musicians. Branford was asking questions that the Bomb Squad either couldn’t or didn’t want to answer, questions like: ‘What key is this in?’ and ‘Could someone count out the tempo?’ and ‘Where’s the chart?’ Meanwhile, Chuck, Hank, Keith and Eric just wanted Branford to play. That must’ve been a funny conversation:

Branford: “What key is this in?”

Chuck: “Just play something.”

Branford: “Could someone count out the tempo?”

Hank: “It’s not loud enough?”

Branford: “Where’s the chart?”

Eric: “Just play something.”

Back in 1989, Public Enemy and Branford Marsalis met on the set of Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing. Branford was working with Spike’s Dad, Bill Lee, to create the movie’s jazz-oriented score. Public Enemy had been tapped to compose and record the movie’s theme song. It was an unlikely combination, but the classically-trained jazz saxophonist Branford eventually collaborated with Public Enemy’s self-trained production team of Hank and Keith Shocklee, Eric Sadler and Chuck D AKA ‘The Bomb Squad.’ The result was “Fight The Power”—a now-classic anthem for the long, hot summer of 1998. One thing always confused me though: although the liner notes read “sax on ‘Fight The Power’ by the one and only Branford Marsalis,” there’s no sax on the record!*

A few years later, I picked up a CD single for “Brothers Gonna Work It Out”—a track from Public Enemy’s 1990 album Fear Of A Black Planet. The fourth track, something called “Powersaxx,” showed me, emphatically, what had happened to all of Branford’s work. Damn!

“Powersaxx” is the instrumental version of “Fight The Power” with simultaneous, chopped-up sax solos from Branford layered atop the mix—one solo in the left channel, one in the right. (A tribute to Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz or complete coincidence? Dunno.) I found out later that there were probably some creative differences in the studio between the musicians. Branford was asking questions that the Bomb Squad either couldn’t or didn’t want to answer, questions like: ‘What key is this in?’ and ‘Could someone count out the tempo?’ and ‘Where’s the chart?’ Meanwhile, Chuck, Hank, Keith and Eric just wanted Branford to play. That must’ve been a funny conversation:

Branford: “What key is this in?”

Chuck: “Just play something.”

Branford: “Could someone count out the tempo?”

Hank: “It’s not loud enough?”

Branford: “Where’s the chart?”

Eric: “Just play something.”

Eventually, Branford recorded several solos and left them in the hands of the Bomb Squad. When Branford heard the final recordings, he must have been dumbfounded. His solo was out of key! Branford’s years of training and playing in the ‘literate’ genres of jazz and classical hadn’t prepared him for the tactics of ‘illiterate’ musicians like the Bomb Squad. Actually, it didn’t prepare him to recognize them as musicians at all. “They’re not musicians,” Branford told an interviewer, “[A]nd [they] don’t claim to be—which makes it easier to be around them. … [T]he song’s in A minor or something, then it goes to D7, and I think, if I remember, they put some of the A minor solo on the D7, or some of the D7 stuff on the A minor chord at the end. So it sounds really different. And the more unconventional it sounds, the more they like it.”

In a piece published in the academic journal Ethnomusicology, Robert Walser responded to Branford’s comments: “Even though he is a ‘real’ musician,” Walser wrote, “Marsalis gets the chords wrong, for the song actually moves between D minor and Bflat7. Of course, this is only a slip of memory, but the casualness and condescension of his account are revealing.” Branford may not have realized it, but the Bomb Squad was intentionally toying with ‘literate’ conventions of music. There was nothing accidental about it. The Bomb Squad enjoyed the dissonance and ‘noise’ they created by layered bits and pieces of Branford’s now-out of key solos atop the shifts, stops and starts of their rhythm track (which was itself meticulously assembled from a wide variety of sources, none of them ‘organic’).

Walser goes on to explain that Branford and Public Enemy were in all likelihood targeting different musical goals. Branford was probably attempting to contribute a harmonically and melodically coherent solo. Public Enemy, on the other hand, were trying to create an appropriately chaotic and ‘noisy’ musical metaphor for the climactic riot which ends Do The Right Thing’s long, hot summer. The louder, harsher and more dissonant, the better. Walser: “The solo in ‘Fight The Power’ has been carefully reworked into something that Marsalis would never think to play, because Shocklee’s goals and premises are different from his [Marsalis’]. Harmonic coherence is not simply a characteristic of ‘musicality’; it signifies, and it doesn’t fit with what Shocklee wanted to signify here.”

Influenced at least in part by his experiences with Public Enemy, Branford would later adopt the name Buckshot LeFonque to record two critically-acclaimed jazz/hip-hop albums. As for “Fight The Power,” it became the rap anthem of the summer of 1998. And the Public Enemy album that “Fight The Power” eventually appeared on, 1990’s Fear Of A Black Planet, was labeled by one New York Newsday writer as “the loudest, most aggressive message of love and faith in the history of pop music.”

*Apparently, Branford’s solo appeared on the single version of “Fight The Power,” but was edited out of the album version. The version I remember—the one in the jukebox—is the album version.

—Mtume ya Salaam

Bonus track:

Public Enemy - “Fight The Power” from Fear Of A Black Planet (Def Jam/Columbia, 1990)

Nothing like this

There is nothing quite like this in jazz precisely because the ‘musicians’ in this case, i.e. the Bomb Squad, were digital technicians rather than instrumentalists, and as such they were not even concerned with theories and practices that serious instrumentalists take for granted, like harmony in the sense of the tempered scale. For them, there is another harmony, a harmony not based on consonance and dissonance, not concerned with how one notes fits with another note, but rather a harmony of the vertical mashing of differing realities occupying the same space. [Very well stated, Baba. —Mtume.]

Eventually, Branford recorded several solos and left them in the hands of the Bomb Squad. When Branford heard the final recordings, he must have been dumbfounded. His solo was out of key! Branford’s years of training and playing in the ‘literate’ genres of jazz and classical hadn’t prepared him for the tactics of ‘illiterate’ musicians like the Bomb Squad. Actually, it didn’t prepare him to recognize them as musicians at all. “They’re not musicians,” Branford told an interviewer, “[A]nd [they] don’t claim to be—which makes it easier to be around them. … [T]he song’s in A minor or something, then it goes to D7, and I think, if I remember, they put some of the A minor solo on the D7, or some of the D7 stuff on the A minor chord at the end. So it sounds really different. And the more unconventional it sounds, the more they like it.”

In a piece published in the academic journal Ethnomusicology, Robert Walser responded to Branford’s comments: “Even though he is a ‘real’ musician,” Walser wrote, “Marsalis gets the chords wrong, for the song actually moves between D minor and Bflat7. Of course, this is only a slip of memory, but the casualness and condescension of his account are revealing.” Branford may not have realized it, but the Bomb Squad was intentionally toying with ‘literate’ conventions of music. There was nothing accidental about it. The Bomb Squad enjoyed the dissonance and ‘noise’ they created by layered bits and pieces of Branford’s now-out of key solos atop the shifts, stops and starts of their rhythm track (which was itself meticulously assembled from a wide variety of sources, none of them ‘organic’).

Walser goes on to explain that Branford and Public Enemy were in all likelihood targeting different musical goals. Branford was probably attempting to contribute a harmonically and melodically coherent solo. Public Enemy, on the other hand, were trying to create an appropriately chaotic and ‘noisy’ musical metaphor for the climactic riot which ends Do The Right Thing’s long, hot summer. The louder, harsher and more dissonant, the better. Walser: “The solo in ‘Fight The Power’ has been carefully reworked into something that Marsalis would never think to play, because Shocklee’s goals and premises are different from his [Marsalis’]. Harmonic coherence is not simply a characteristic of ‘musicality’; it signifies, and it doesn’t fit with what Shocklee wanted to signify here.”

Influenced at least in part by his experiences with Public Enemy, Branford would later adopt the name Buckshot LeFonque to record two critically-acclaimed jazz/hip-hop albums. As for “Fight The Power,” it became the rap anthem of the summer of 1998. And the Public Enemy album that “Fight The Power” eventually appeared on, 1990’s Fear Of A Black Planet, was labeled by one New York Newsday writer as “the loudest, most aggressive message of love and faith in the history of pop music.”

*Apparently, Branford’s solo appeared on the single version of “Fight The Power,” but was edited out of the album version. The version I remember—the one in the jukebox—is the album version.

—Mtume ya Salaam

Bonus track:

Public Enemy - “Fight The Power” from Fear Of A Black Planet (Def Jam/Columbia, 1990)

Nothing like this

There is nothing quite like this in jazz precisely because the ‘musicians’ in this case, i.e. the Bomb Squad, were digital technicians rather than instrumentalists, and as such they were not even concerned with theories and practices that serious instrumentalists take for granted, like harmony in the sense of the tempered scale. For them, there is another harmony, a harmony not based on consonance and dissonance, not concerned with how one notes fits with another note, but rather a harmony of the vertical mashing of differing realities occupying the same space. [Very well stated, Baba. —Mtume.]

Check out this interview with Chuck D and Hank Shocklee (http://www.stayfreemagazine.org/archives/20/public_enemy.html)

if you really want to know more about ‘how’ the Bomb Squad approached their music. Although they mainly focus on sampling, the exchange does touch on some of the theoretical concepts underlying their approach.

The closest to this in jazz is Ornette Coleman’s harmolodic concept. In literature we have the Dada techniques, most famously the William Burroughs cut up method, which is simply the taking apart of something and the putting it back together, either randomly or by some predetermined pattern that results in the juxtaposition of various words colliding in ways not originally conceptualized. Regardless of what one thinks of these experiments, all of them pale next to what the Bomb Squad achieve precisely because in the Bomb Squad’s work there is a conscious determination toward sonic fusion.

Moreover, Branford, for all his genius and skill, could never have created “Powersaxx” (even though it features his hot horn up front in the mix) precisely because his learning would have gotten in the way. Unavoidably, he hears keys and relates to that. The Bomb Squad hears sounds as raw vibrations. Their frame of musical reference is the beat, the groove, it doesn’t much matter what key because they will play the sounds against each other atop the groove.

Who knows how they thought up this approach or if they actually 'thought' it up at all, as opposed to it happening as they experimented. I remember interviewing George Clinton—he talked about how they would go into a studio, invite the engineers out, and just start pushing buttons to see what would happen if…. Pure experimentation. Or as I am wont to quip when confronted with the task of doing something new, Negroes never let ignorance stop them from doing something. Or, to put it more poetically, the Bomb Squad did what they did precisely because they didn’t know they were not supposed to be able to do what they did.

Moreover, it’s hard—really, really hard—to mesh dissonance into a groove. But sonically, this is nothing but quilting, except the needle and thread is digital technology, and the pieces of cloth are samples, found sounds (sirens, glass breaking, gun shots, etc.) and human expressions. Branford was looking for a band to play with, a song to play. All the Bomb Squad wanted was some of Branford wailing.

On a more trivia kind of vibe, I note that while Branford started on alto saxophone and was adept at that, Wynton (Branford’s brother) pushed him to play tenor. The awesomeness of John Coltrane’s model and influence not withstanding, the major sonic developments in terms of harmony in post-WW2 jazz were by Charlie Parker (by adding harmonic complexity) and Ornette Coleman (by doing away with the dominance of Western harmony), both of whom also played alto. I think there is something that remains lyrical about the alto even at its harshest and most ‘out’ moments—I am thinking of Anthony Braxton and his predecessor Eric Dolphy. In fact, I could argue that Braxton used some of the non-Western musical theory in his music, but the real deal, or should I say, the real relevance to “Powersaxx” is that none of the jazz players were into the deep grooves—no, not even Miles Davis in his electric funk days.

The point is, rap is a different kind of music (although recent developments keep pushing it more and more toward merging back into the Western approach to music, nevertheless, we have documents such as this to indicate that there is another way).

Now that said, although I have no idea where they got their harmonic sense, I am fairly certain the groove part of the Bomb Squad approach comes from James Brown, and his main man on horn was, of course, Maceo Parker, as in “blow, Maceo, blow.”

Check out this interview with Chuck D and Hank Shocklee (http://www.stayfreemagazine.org/archives/20/public_enemy.html)

if you really want to know more about ‘how’ the Bomb Squad approached their music. Although they mainly focus on sampling, the exchange does touch on some of the theoretical concepts underlying their approach.

The closest to this in jazz is Ornette Coleman’s harmolodic concept. In literature we have the Dada techniques, most famously the William Burroughs cut up method, which is simply the taking apart of something and the putting it back together, either randomly or by some predetermined pattern that results in the juxtaposition of various words colliding in ways not originally conceptualized. Regardless of what one thinks of these experiments, all of them pale next to what the Bomb Squad achieve precisely because in the Bomb Squad’s work there is a conscious determination toward sonic fusion.

Moreover, Branford, for all his genius and skill, could never have created “Powersaxx” (even though it features his hot horn up front in the mix) precisely because his learning would have gotten in the way. Unavoidably, he hears keys and relates to that. The Bomb Squad hears sounds as raw vibrations. Their frame of musical reference is the beat, the groove, it doesn’t much matter what key because they will play the sounds against each other atop the groove.

Who knows how they thought up this approach or if they actually 'thought' it up at all, as opposed to it happening as they experimented. I remember interviewing George Clinton—he talked about how they would go into a studio, invite the engineers out, and just start pushing buttons to see what would happen if…. Pure experimentation. Or as I am wont to quip when confronted with the task of doing something new, Negroes never let ignorance stop them from doing something. Or, to put it more poetically, the Bomb Squad did what they did precisely because they didn’t know they were not supposed to be able to do what they did.

Moreover, it’s hard—really, really hard—to mesh dissonance into a groove. But sonically, this is nothing but quilting, except the needle and thread is digital technology, and the pieces of cloth are samples, found sounds (sirens, glass breaking, gun shots, etc.) and human expressions. Branford was looking for a band to play with, a song to play. All the Bomb Squad wanted was some of Branford wailing.

On a more trivia kind of vibe, I note that while Branford started on alto saxophone and was adept at that, Wynton (Branford’s brother) pushed him to play tenor. The awesomeness of John Coltrane’s model and influence not withstanding, the major sonic developments in terms of harmony in post-WW2 jazz were by Charlie Parker (by adding harmonic complexity) and Ornette Coleman (by doing away with the dominance of Western harmony), both of whom also played alto. I think there is something that remains lyrical about the alto even at its harshest and most ‘out’ moments—I am thinking of Anthony Braxton and his predecessor Eric Dolphy. In fact, I could argue that Braxton used some of the non-Western musical theory in his music, but the real deal, or should I say, the real relevance to “Powersaxx” is that none of the jazz players were into the deep grooves—no, not even Miles Davis in his electric funk days.

The point is, rap is a different kind of music (although recent developments keep pushing it more and more toward merging back into the Western approach to music, nevertheless, we have documents such as this to indicate that there is another way).

Now that said, although I have no idea where they got their harmonic sense, I am fairly certain the groove part of the Bomb Squad approach comes from James Brown, and his main man on horn was, of course, Maceo Parker, as in “blow, Maceo, blow.”

Is it just coincidence that Maceo Parker also plays alto saxophone? Yet, even Maceo is no where near what the Bomb Squad was doing. All of the afore-mentioned alto saxophonists are musicians, acclimated to Western harmony. The Bomb Squad is some other shit. And that’s what I like about it. It’s otherness!

As for that “Escape-ism” excerpt, that’s St. Clair Pinckney, who played tenor and baritone saxophone with James Brown. “Pink” was particularly enamored of late-period Coltrane, which include playing in the extreme upper register of the tenor. The “Superbad” reference is to St. Clair’s iconic avant garde jazz solo atop the JB groove on that particular recording. It’s not the same as what either Branford does on “Powersaxx” or what Maceo generally did with JB, but it does have a similar feel, i.e. a wailing saxophone over a heavy groove.

Final trivia note: Branford got the Buckshot persona from jazz alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley who ghosted on a number of R&B recordings either uncredited or under a pseudonym. And Branford is deep into computers.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

100% correct – the J.B. influence

Baba, you are 100% correct about the J.B. influence. Listen closely and you’ll hear that the backbone of the “Fight The Power” rhythm track is the archetypal “Funky Drummer” break. I say, ‘archetypal’ because James Brown’s break—or, more accurately, Clyde Stubblefield’s break—has been used in so many rap and pop records that it is no longer recognizable as anything other than ‘that beat.’ I don’t think most people would even realize it’s a sample.

Not only was the Bomb Squad deeply influenced by J.B., all hip-hop producers of P.E.’s generation were/are indebted to the Godfather. (Not to mention that pre-recorded hip-hop was also deeply influenced by J.B.) I wouldn’t be surprised at all if the Bomb Squad got the idea of layering a sax solo onto their mix while listening to J.B. records like “Super Bad.” In fact, check out the jukebox and listen to the brief excerpt from the 19 minute-long (!!!) funk-fest entitled “Escape-ism” back to back with "Powersaxx" and notice how similar the effect is. Both tracks feature ‘out’ sax playing over a dense groove. The differences are obvious as well (mechanical vs. organic, frenetic vs. ‘cool,’ etc.) but the similarity is obviously there.

—Mtume ya Salaam

All on one

Guess what? The 'recently updated' official Do The Right Thing soundtrack album now has the original "Fight The Power," "Powersaxx" and the extended single (the version with Branford's solo), plus a bunch of other hip songs from that era. Amazon has used copies for less than $5—what y'all waiting for?

Is it just coincidence that Maceo Parker also plays alto saxophone? Yet, even Maceo is no where near what the Bomb Squad was doing. All of the afore-mentioned alto saxophonists are musicians, acclimated to Western harmony. The Bomb Squad is some other shit. And that’s what I like about it. It’s otherness!

As for that “Escape-ism” excerpt, that’s St. Clair Pinckney, who played tenor and baritone saxophone with James Brown. “Pink” was particularly enamored of late-period Coltrane, which include playing in the extreme upper register of the tenor. The “Superbad” reference is to St. Clair’s iconic avant garde jazz solo atop the JB groove on that particular recording. It’s not the same as what either Branford does on “Powersaxx” or what Maceo generally did with JB, but it does have a similar feel, i.e. a wailing saxophone over a heavy groove.

Final trivia note: Branford got the Buckshot persona from jazz alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley who ghosted on a number of R&B recordings either uncredited or under a pseudonym. And Branford is deep into computers.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

100% correct – the J.B. influence

Baba, you are 100% correct about the J.B. influence. Listen closely and you’ll hear that the backbone of the “Fight The Power” rhythm track is the archetypal “Funky Drummer” break. I say, ‘archetypal’ because James Brown’s break—or, more accurately, Clyde Stubblefield’s break—has been used in so many rap and pop records that it is no longer recognizable as anything other than ‘that beat.’ I don’t think most people would even realize it’s a sample.

Not only was the Bomb Squad deeply influenced by J.B., all hip-hop producers of P.E.’s generation were/are indebted to the Godfather. (Not to mention that pre-recorded hip-hop was also deeply influenced by J.B.) I wouldn’t be surprised at all if the Bomb Squad got the idea of layering a sax solo onto their mix while listening to J.B. records like “Super Bad.” In fact, check out the jukebox and listen to the brief excerpt from the 19 minute-long (!!!) funk-fest entitled “Escape-ism” back to back with "Powersaxx" and notice how similar the effect is. Both tracks feature ‘out’ sax playing over a dense groove. The differences are obvious as well (mechanical vs. organic, frenetic vs. ‘cool,’ etc.) but the similarity is obviously there.

—Mtume ya Salaam

All on one

Guess what? The 'recently updated' official Do The Right Thing soundtrack album now has the original "Fight The Power," "Powersaxx" and the extended single (the version with Branford's solo), plus a bunch of other hip songs from that era. Amazon has used copies for less than $5—what y'all waiting for?  —Kalamu ya Salaam

Click here to purchase Do The Right Thing Soundtrack

—Kalamu ya Salaam

Click here to purchase Do The Right Thing Soundtrack

Branford Marsalis weighs in

Because of timing issues, we got it backwards. Our secret goal was to interview Branford Marsalis and include the interview with the write-up about “Powersax,” however, the timing didn’t work out and we didn’t get to talk to Branford until after the article was posted, but we pressed on anyway, prepared, if necessary, to print exactly what Branford said to correct our assumptions, suppositions and speculations.

On Sunday morning, 14 August, Mtume and I interviewed Branford Marsalis by phone. After our talk, Mtume and I laughed with each other. There was no need to print the interview—Branford said what we had said. Right down to specific references: James Brown, Maceo, not working from a western tradition of harmony, using a cut-up technique, the Bomb Squad was on some other kind of vibe, etc.

Mtume and I were laughing while we were doing the interview and telling Branford he was saying what we had already said.

To be more accurate, nothing Branford said contradicted or required us to amend or withdraw anything we said. So that was that.

Except… you know with ‘negroes’ there is always an exception—except it turns out Branford actually did three solos rather than two: one in a jazz mode, “mostly be-bop licks”; another in a “Maceo” mode; and a third sort of like "John Gilmore" (long-time tenor saxophonist with Sun Ra, credited with being an influence on John Coltrane).

Branford also said he learned a lot from working with the Bomb Squad and was particularly complimentary of Eric Sadler, the least known of the four Bomb Squad (Chuck D, Hank and Keith Shocklee) members. But Branford qualified his learning experience by noting they weren’t musicians in the sense of what he knew a musician to be. They didn’t hear “music” or “notes,” they heard “sound.” At which point it was sort of like, hey, we already wrote this…

So we ended up talking a bit about the music business, about rap, about singers and the lack of singing ability, about how production techniques have affected musicians, and so forth, and then Branford signed off, and then Mtume and I talked for a long time trying to figure out what we were going to do.

I just did it. Thank you. Good night.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

On Sunday morning, 14 August, Mtume and I interviewed Branford Marsalis by phone. After our talk, Mtume and I laughed with each other. There was no need to print the interview—Branford said what we had said. Right down to specific references: James Brown, Maceo, not working from a western tradition of harmony, using a cut-up technique, the Bomb Squad was on some other kind of vibe, etc.

Mtume and I were laughing while we were doing the interview and telling Branford he was saying what we had already said.

To be more accurate, nothing Branford said contradicted or required us to amend or withdraw anything we said. So that was that.

Except… you know with ‘negroes’ there is always an exception—except it turns out Branford actually did three solos rather than two: one in a jazz mode, “mostly be-bop licks”; another in a “Maceo” mode; and a third sort of like "John Gilmore" (long-time tenor saxophonist with Sun Ra, credited with being an influence on John Coltrane).

Branford also said he learned a lot from working with the Bomb Squad and was particularly complimentary of Eric Sadler, the least known of the four Bomb Squad (Chuck D, Hank and Keith Shocklee) members. But Branford qualified his learning experience by noting they weren’t musicians in the sense of what he knew a musician to be. They didn’t hear “music” or “notes,” they heard “sound.” At which point it was sort of like, hey, we already wrote this…

So we ended up talking a bit about the music business, about rap, about singers and the lack of singing ability, about how production techniques have affected musicians, and so forth, and then Branford signed off, and then Mtume and I talked for a long time trying to figure out what we were going to do.

I just did it. Thank you. Good night.

—Kalamu ya Salaam

This entry was posted on Sunday, August 14th, 2005 at 12:01 am and is filed under Classic. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

7 Responses to “PUBLIC ENEMY feat. Branford Marsalis / “Powersaxx””

August 14th, 2005 at 1:50 am

Fight the Power was a major statement in 89. Spike Lee had shot the video for this summer sizzler in Bed Stuy (do or die) Brooklyn. A rally ensued and there were some actual discourse about nation building (imagine that). You can hear snippets of the Branford version towards the end of that classic video.

It was ingenious to have Flava Flav (the resident coon/jester) say “muthafuck him (elvis) and john wayne" in reference to our heroes not appearing on stamps, instead of the group leader/activist Chuck D. This showed that every Blackman was on board to fight the system.

I remember how hot it was that summer, and how hype we were in the theatre every time “radio raheem” came on the scene with the boom box blasting Fight The Power.

As a fan of hip hop, I would be remised if I didn’t point out this fact:

Fight the Power was the final public enemy song produced by the bomb squad (hank shocklee left the group before “fear of a black planet’ was recorded). After his departure, their sound was never the same. No songs, post fight the power, came close to the bar that was set by PE during spike lee’s best movie (four little girls was a documentary), or any cut on “It takes a nation on millions to hold us back” (PE’s classic 2nd album).

-nadir

Mtume says:

Gotta disagree with you Nadir. "By The Time I Get To Arizona." "Can’t Truss It." "Hazy Shade Of Criminal." "Live & Undrugged" (especially Part 2). All of these cuts were done post-"Fight The Power" and are at least the equal of anything P.E. on their first two albums. IMO, 1990’s-era P.E. is vastly underrated.

August 14th, 2005 at 6:14 am

Every time I hear “Fight The Power,” I am pulled back to late eighties NYC and my political awakening. Around that time, I remember going to my first rally on the steps of a courthouse in Brooklyn where Joseph Fama was being tried for the murder of Yusef Hawkins. I had read Malcolm’s autobiography and the world was looking different to me. “Fight The Power” embodied many things I felt at that time.

Public Enemy is AMAZING because they conjure a mood, they never let you chill with blindfolded eyes. Yes, “By the Time I get To Arizona” and “Can’t Truss It” –and the videos–were VERY powerful. Two years ago I saw PE in London and I am telling you, I left that theater with chills, I was not ready to leave or even have drinks, I was ready to get in the trenches. They did this joint called “What Good Is A Bomb”–whew.

A few years ago, a friend and I talked about how the hip-hop in the late eighties and early nineties used to send us to the library; hell, it even made us reconsider our diets (Beef by KRS) ![]() . Mtume, I think you wrote about this period in hip hop last week and said it didn’t do much for you, but something tells me that you were already very aware; for me that musical period coincided with an awakening . “Fight The Power” is defintely THE rally cry Anyway, I wish hip-hop still moved me like “Fight The Power” does.

. Mtume, I think you wrote about this period in hip hop last week and said it didn’t do much for you, but something tells me that you were already very aware; for me that musical period coincided with an awakening . “Fight The Power” is defintely THE rally cry Anyway, I wish hip-hop still moved me like “Fight The Power” does.

Mtume says:

Wow. There aren’t too many things I read or hear that cause me to COMPLETELY reevaluate things, but one line Ekere wrote definitely did that. He She (sorry) said: "You wrote about this period in hip hop last week and said it didn’t do much for you, but something tells me that you were already very aware; for me that musical period coincided with an awakening."

There is a lot, a whole lot, of truth in that. I guess so much time has passed since then, that I’ve forgotten what it meant to people—especially young Black people—to see those images (firehoses, lynchings, bombings) and hear those things (X, King, Davis, Chesimard/Shakur, etc.) for the first time. I grew up seeing and hearing those images. There was a book in our house of first-hand accounts from the days of slavery. By the time we kids (there were five of us) were eight or nine years old, we’d all read it cover to cover. And not because we ‘had’ to, we read it just because it was on our bookshelf. We had no TV—we actually read for fun. Hell, WE HAD A BOOKSHELF!!! I just realized what I wrote. How many children grow up with a frickin’ bookshelf—not a collection of kiddie books, but honest to goodness, politically-charged, factually-accurate books—in their rooms? (Well, not always factually accurate. Remember the comic-book-style histories of the adventures of Mao’s army, Baba? All the heroes were women who were big and strong and young and gorgeous and unafraid, striding their fine-ass, fearless selves into the glorious, perfect future-to-be with an automatic rifle in their hands and a baby strapped on their backs. What was that all about? Talk about propaganda. I should sue.  )

)

But on the serious tip, Malcolm X has been a hero figure for me for as long as my memory extends back. (Since at least five, six years old.) I was 21 years old when Spike Lee’s X came out and I already knew the story so well (The Autobiograpy of Malcolm X) that I got aggravated every time the movie deviated from the book. (Which was very often—particularly in the first third or so.) On the walls in our family home there were paintings and photographs of the same political figures who would eventually find their way onto the album jackets of my 12" singles. We had a Black Liberation flag (red, black & green for those not in the know) in the house. We had a map of Africa (with countries and capitol cities listed) in the house.

Last night, I saw Four Brothers (it’s worth seeing by the way, just keep in mind that it’s a movie, not a film; meaning, it wants to entertain you, not teach you/move you/hurt you/help you, etc.), and I couldn’t believe the number of children in there. The movie is rated R for all the reasons movies should be rated R and by ‘children’ I don’t mean twelve- and thirteen-year-olds (although the movie is clearly inappropriate for them too), I’m talking about two- and three-year-olds. At first I wrote it off as a generational thing ("Man, these young people today need help") but as the closing credits rolled, my sister Asante (‘Thank you, Peace’ in Swahili) and my Mama, Tayari (‘Always prepared for Peace’—dig the names, y’all), and I, sat there amazed (well, I was amazed—they were like, "You need to get out more") as we watched a pair of sixty-somethings walk out holding the hands of a little girl who couldn’t have been more than three years old. About half the audience was white, but all of the kids I saw in there were Black. Which reminds me of a Raphael Saadiq song, "Grown Folks," that I need to post one of these days. The chorus—"Lord, help these grown folks / They need more help than the children do"—is true like a motherfucker. How do you think the children got that way? They’re not raising themselves. Well, actually, they are—which is exactly the fucking problem. Those grandparents I saw last night need one of my Baba’s classic ass whippings (which entailed severe pain followed by a candle-lit, one-on-one dinner date to discuss why your ass was hurting so much in the first place). In less than two hours, their poor little grand-daughter had seen and heard more sex, violence, profanity and negative images of Black folk than I saw and heard during my entire childhood. (By the way, I’m joking about the whipping thing. There never were any candles.)

Anyway, y’all can tell how hard Ekere’s line hit me. (Wait, hold on. "There never were any candles." Oh, that’s good. Wait ’til my Baba reads that part. I probably just won’t answer the phone.  ) When I evaluate an issue, I try to leave my personal opinion out of it (as ridiculous as that sounds—and yes, I’m aware that it’s impossible to actually do so) and simply ‘go with the facts.’ Well, the facts in this case are that the political era in hip-hop was very, very meaningful to a great number of young people. I forget that. It was the first time some of my young people ever heard X or King speak. I forget that. It was the first time they ever saw images of the slave ships or the cotton fields or the fire hoses. I forget that. It was the first time they ever felt strong and beautiful because of, as opposed to ‘in spite of’ (or as opposed to ‘at all’) their dark skin, wide features and nappy hair. I grew up singing songs with lyrics like, "Look at [name] she/he’s Black and beautiful!" For us, that was a nursery rhyme (and I’m not kidding). So, again, I forget.

) When I evaluate an issue, I try to leave my personal opinion out of it (as ridiculous as that sounds—and yes, I’m aware that it’s impossible to actually do so) and simply ‘go with the facts.’ Well, the facts in this case are that the political era in hip-hop was very, very meaningful to a great number of young people. I forget that. It was the first time some of my young people ever heard X or King speak. I forget that. It was the first time they ever saw images of the slave ships or the cotton fields or the fire hoses. I forget that. It was the first time they ever felt strong and beautiful because of, as opposed to ‘in spite of’ (or as opposed to ‘at all’) their dark skin, wide features and nappy hair. I grew up singing songs with lyrics like, "Look at [name] she/he’s Black and beautiful!" For us, that was a nursery rhyme (and I’m not kidding). So, again, I forget.

I could go on (and on and on and on) but I’m going to stop now. Just know, Ekere, that I respect what you had to say and I’ll remember it. For me, the messages of the political hip-hop era might’ve been a review; for most, it was probably a baptism. Hip-hop music, baby.

August 15th, 2005 at 5:12 pm

Mtume,

You know what’s bugged out? I had a set of encyclopedias and a rack of Hardy boys books, but my parents had three, count’em, 3 books in the house NOT related to church- a reader’s digest trilogy that included Jaws, Alex Haley’s Roots, and the Autobiography of Malcolm X….I had read excerpts of the first two before I was twelve, and then at thirteen, I finally pulled that tattered book with the angry man wearing glasses pointing off of the coffee table. It was 1984 Bruh and LL Cool J was hard as …HELL.

Needless to say, things changed. Couple my reading of the Autobiography with the appearance of one Rakim Allah and next thing you know, it was on. PE’s ascension of interesting, because when their first album, ‘Yo, Bum Rush The Show’ came out, nobody in my area liked it, me included. I thought Chuck’s voice was dope, but he was trying to experiment with flows that didn’t rhyme, and at that point, that was a no-no in Hip-Hop. But when they dropped ‘Rebel Without a Pause’ as a b-side to the single ‘My Uzi Weighs A Ton’-‘Rebel’ that was when PE took off.

PE, along with BDP were the groups that jump started ‘conscious Rap’, and for those of us who weren’t initiated into a family where liberation struggle was an everyday function, they are extremely important. For the first generation that was brought up in front of the color TV (with cable), having a group that was part of Pop culture ‘in crowd’ provided reinforcement that at least led us to investigate…like who is Joanne Chesimard and why is Chuck supporting her? That kind of thing is why PE carries weight even with Flav bugging out….

August 16th, 2005 at 1:42 pm

This is truly a stolen legacy.

It is an extremely interesting phenomenon how rap music is raising itself while simultaneously defending itself from attackers of both native and foreign origin. I know many claim that rappers are not ‘real’ musicians or how rappers steal others music. Try to avoid this perception. If rap music is a forest then this argument is the thin veneer covering porous walls that small people wish were sound proof. A tree fell and even if you didn’t hear it, if you were down with your roots, you felt the vibrations.

Any sensible person should admire one who has the awareness to carve and hollow-out a tree trunk, stretch a goat’s hide across the top and make a drum. Or what about a person who takes a wooden box, connects a pole and strings cat guts to make a stringed instrument and then uses this to accompany him/herself while singing. This is the same creativity employed by rap. It is both Black and organic. Rap is the sound of life and if this sound concerns you then you must certainly ask yourself why because it is the sound your children use to reflect the world.

Look at the culture and music of the BaBenzele or the BaMbuti people of the Ituri forest as an example: these people (erroneously referred to as pygmies) see themselves as simply another organism, of no more or less importance than any other organism, in the forest. The BaMbuti derive 100% of their sustenance from the forest. They give thanks to the larger organism of the forest as a whole by mimicking and singing in harmony with the sounds of the forest. It is an ecstatic cacophony of harmony, ensemble performance, soloing, call and response and trading verses. It is the sound of their environment. Hello Bomb Squad.

At its best, rap is an inherently gifted descendant reflecting the resourcefulness of African culture while projecting its own unique I AMness across the diaspora. Rap utilizes whatever means necessary to compel you to hear the world. Perhaps the world is changing and your ears have become complacent.

Taking music out of public schools doesn’t necessarily mean you can take away music. It may not sound like what you are used to hearing but most rap is not music in the traditional sense though it is definitely artistic expression. The underlying sound may very well be bombs, gunshots, sirens, shouts, traffic and other ‘urban’ sounds surgically cut into dense, tightly packed grooves of funky drum beats and booming bass lines. This is the soundtrack to life for the majority of Black youth. But rap music is being forced to grow up too fast because the children are being forced to grow up too fast. Not enough time is being spent nurturing our children. Commerce is not allowing the children their childhood. And even though the music may swing, the sound of dissonance is evidence that there’s a lot of shit that ain’t been resolved. We have not shown our children how to resolve the seventh chords of life. Who’s gonna take ‘em to the bridge? Who’s going to show today’s youth how to navigate the channels connecting streams of awareness to oceans of consciousness? Who’s gonna break down the hipness of the 2-5-1 turn around? I’ll tell you who. Nobody, that’s who, because in the age of computers, software, internet and virtual reality it’s not about music in the known sense. (It’s becoming less and less about a human teacher or positive human contact.) Whether real or virtual, it’s more about sound. They weren’t asking Branford to play a D7 or Bbm7. They were asking Branford to play Branford. We’ve been practicing revolution for over four hundred years; let’s get free. Or at least give me the sonic equivalent to how you feel about life, the world. It’s an honest request. But in Branford’s world there is a universe of discipline that has to be mastered before you can attain that freedom. Sun Ra’s Arkestra sounds like the last jazz on earth yet Sun Ra demanded discipline. I imagine one of the reasons Branford thought John Gilmore on Powersax was because Gilmore had spent damn near his whole adult life learning discipline with Sun Ra and the Arkestra and as a result that education delivered freedom to Gilmore and those who heard the urgency of his tenor. For those who don’t know just who John Gilmore is find the recording Sun Ra Live at Montreux and listen to Take The A Train.

But in this case there ain’t no chart because The Bomb Squad doesn’t need their shit to conform to the same old ways. This time the revolution will not be telegraphed by charts. Welcome to the Terrordome; a musical collage of all sounds scored by (orchestrator) turntablist, (accompanist) human beatboxes and (soloist) mc’s, So part of rap’s legacy is that it broke down beats in ways beats ain’t never been broke before. This beat down was a major battle that almost broke the music industry. It just goes to show you that in this power-mad, money-crazed world ain’t shit safe or sacred. Anybody can get got and anybody can get free. Everybody get a damn bookshelf! Know Yourself. Do your thing. Fight the power.

AumRa

April 8th, 2006 at 11:48 pm

Thanks so much for all this information… I am remaking all the samples that PE usedon Nation& Fear (sound-alikes), and then re-mashing them together to recreate Instrumental versions of those CD’s. Part of the rights to the sounds will be owned by the Zulu Nation, part owned by me, part Public Enemy, and part a tribe in the Amazon Rain Forest called the Schuar.

My dream is to bring these remixes down to the Amazon in the future and teach my friends down there how to remix these tracks. And teach their neighbor tribes how to do the same … I’ve talked to Chuck & Hank & the s1w’s about this , hopefully they can come down and bring the “Flavof all Flavors”.

I really appreciate the scholarship … Powersaxxx is one of my favorite tracks, too!

What’s interesting most to me about Brandford’s sax is that on the chorus, when the track goes to Bb Major (really Bb Major 7th because the original guitar groove has an “A” in it), Brandford makes it into a BbDominant 7th chord… which means during that part he must have heard the chord change to Bb. Otherwise, if hadn’t played the Ab in the Bb7 chord, he could have played the same Dminor (really dorian, I think) mode/scale over the chorus and it would have worked. Obviously I’m speaking from a strictly technical sense, since the Blues notes he puts into the chorus part show that he heard it as a BbDominant (NOT Major) 7th chord. ie it’s rare for a musician to play blues notes over a major 7th chord.

Anyway, I have pictures of me with Hank, Chuck, and Rod Hui (inventor of the 808 boom) on my myspace.com/raspberryx page.

I will have info up on http://www.chrisdefendorf.com this year.

Please send me an email if you’d like to hear some dubby versions I made of the “Fight the Power ” track. I remade the Funkadelic “You’ll like it too” beat , “Hot Pants Road” drums, guitar & bass line, “FunkyDrummer” beat, “Let a Woman Be a Woman and a Man be a aMan” beat, as well as all the other little sounds that make up the basic part of the “Fight the Power” groove. Then I added analog echo effects to the mix and dubbed it out into 2 mixes, each around 10 minutes long…

email me at christopherdefendorf@gmail.com for some sounds!

peace. i haven’t read everything that’s been written, but I’m psyched that all of you are writing about this one song…

Fight the Power,

Peace, Unity, Love, and Having Fun,

Chris Defendorf

True School

aka DJ Chris Def

aka Raspberry

aka As8auQaa (pronounced Ahh-Sahh-Haaaa)

April 17th, 2006 at 2:04 pm

yo public enemy is sick i wish they were back but there legends now so respect i love the song fight the power respect shout out to public enemy number 1.

Leave a Reply

| top |